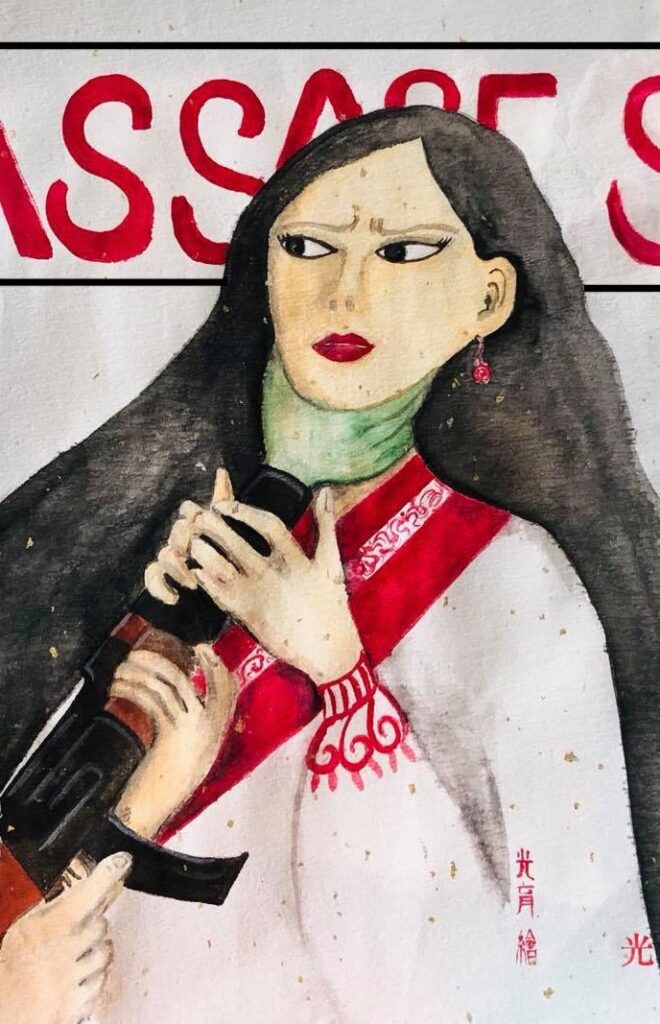

episteme issue 6 is presented as a forum, organized in response to Atlanta Spa Shooting and seeks to understand the racial-historical and geopolitical roots of anti-Asian racism and the shortfalls of the liberalist response to it.

On March 16, 2021, Robert Aaron Long, a twenty-one year-old white man from Woodstock, Georgia, went on a mass shooting rampage at three massage parlors in Atlanta, killing eight people, six of whom are identified as Asian women. A Christian of the Southern Baptist Congregation, Long pleaded that the killing was motivated by a sexual addiction that was at odds with his religious beliefs; this served to disassociate the killing from any racial implication and to cast the blame instead on the victims. This tragic incident saddened and enraged the Asian American community, a community already burdened by the alarming rise of hate-crimes against Asians that quickly emerged globally with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020. With the identification of six victims in Atlanta as Korean and Chinese immigrants, the mass shooting also garnered international attention. Both the South Korean and Chinese governments made public announcements to express regret and denounce racism, urging the US government to protect its citizens from harm. The tragedy also raises concerns about the possible reinforcement of the overtly sexualized stereotypes of Asian women in the US, thus rubbing salt on the oozing wounds of Asian Americans who have become the target of race hatred, especially after Donald Trump, former president of the United States, unabashedly called COVID-19 the “China Virus” and “Kungflu.” …

… The migrant connection to China moreover raises worries that the Atlanta shootings might complicate the already tense US-China relation, allowing China to use the incident as leverage against the US. With the death of George Floyd that triggered the Black Lives Matter activism, the Atlanta Shooting painfully brought into view the dense articulation of racism, sexism, and xenophobia. The complexly uneven and precariously entangled transpacific life worlds that conditioned our perception of this tragedy raises the issue of what justice means and how peace is possible.

It is out of these urgent calls for justice and peace after the Atlanta Shooting that we organized a roundtable on “Anti-Asian Hate and Sinophobia: A Global Analysis” on March 31, 2021, at the Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan, to discuss these complex and troubling questions. Where the Atlanta tragedy was widely covered in the mainstream media, we thought what was lacking is an analysis of the internal fissures and transpacific dissonances of anti-Asian racism that are either amplified by US-China rivalry or covered up by the call for a rainbow coalition where non-citizen migrants are often left in limbo. In particular, we wanted to fill the void with voices of Chinese student activists who must navigate their political commitments through PRC state surveillance, US and UK stratified immigration systems, and their disconnection from Asian American and Asia diaspora communities. As scholars and activists based in Taiwan, we also wanted to explore how the new Cold War between China and the US affects our understanding of the tragedy and is shaping our response to it; how might a focus on non-citizens loosen up the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI hereafter) framework of recognition and assimilation? The essays collected here are the result of this roundtable. I want to thank Wendy Cheng, Kun Huang, Wen Liu, Flair Donglai Shi, and Yihung Liu for their participation and comradeship, the positionspolitics.org site for publishing them, and especially Rebecca Karl for her superb editorship and help. I also want to thank Jih-Fei Cheng, Chu-wen Hsieh, Ying-chao Kao, Lu Pin, and others for joining the conversation in Taipei. The pain and hurt of the victims’ families is the basis of our forum and we want to acknowledge that here.

While the Asian American community lamented the passing of the six women in Atlanta, remembering that anti-Asian racism is nothing new in US history, Chinese students in the United Kingdom started a campaign to urge UK universities to stop Sinophobia and anti-Asian racism by recognizing “the pain felt by Asian students amidst increasing rampant anti-Asian racism and devot[ing] more support and resources” to help them better protect themselves against hate crimes. Though the term “Asian” has a somewhat different connotation in the UK context than in the US, the Chinese students’ focus on both Sinophobia and anti-Asian racism in the UK demands a comparative and geopolitical analysis of COVID-fueled anti-Asian hate as a global phenomenon. It asks us to think beyond the AAPI framework to consider recent changes in geopolitics and more carefully differentiate the subjects—migrant workers in the massage parlors, US-born Asian Americans, and international students—implicated in the global racism against Asians. It also urges us to consider what lies behind anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia: is it anxiety about and ignorance of racial others that have long lived amongst us? A deep-seated fear of communism? And/or a worry over the decline of Pax Americana? While the Atlanta Shooting is a singular event, our response to it is conditioned by a wide spectrum of emotions and politics.

At a time when certain groups, such as Taiwanese and Hong Kongers, are engaged in a process of dis-identifying with China and Chinese-ness, the anti-Asian racism framework that includes all Asians indiscriminately, while still a useful strategy for activism, may have overlooked the complex inter-Asian relations in the historical formations of Asian America and its precarious linkages to Asia. Just as the PRC and the US went through multiple rounds of difficult conversation regarding issues including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang, in Anchorage, Alaska, which a BBC analyst called “unusually undiplomatic,” anti-Asian hate and Sinophobia seem to have become a companion phenomenon in a new Cold War framework where the role of Taiwan is peculiar to say the least. In fact, when the world was beleaguered by the pandemic in 2020, Taiwan was one of the few countries that was able to keep it at bay by enforcing strict social distancing as well as border measures to keep out visitors from China, including its own citizens trying to return home from Wuhan. It also initiated the “Taiwan can Help” campaign to donate masks to the world (except to China), to assert its difference from China. The Tsai Ing-wen administration continues to insist on calling COVID-19 “Wuhan virus” even as the Taiwan-China relations have deteriorated dramatically to the point that The Economist ran a special issue in May 2021 calling Taiwan “the most dangerous place on Earth,” worrying that a war on Taiwan may be imminent. These scenarios have produced a strong image of the China threat in Taiwan, especially among the younger generation, which rendered them less susceptible to the pain and hurt of Asian Americans that suffer anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia. If a Taiwanese is unfortunately attacked in an anti-Asian racism incident, the hatred for China increases, and they argue that building a Taiwanese identity is the solution. In practice, of course, the perpetrators of anti-Asian racism do not differentiate Japanese from Chinese, let alone Taiwanese from Chinese; nevertheless, the Taiwanese response to anti-Asian racism suggests how the shifting geopolitical realignment may complicate the meanings of racism in the context of what Wen Liu in her contribution to this forum calls “imperialist rivalry” that carry Cold War ideological baggage.

Based in Taiwan, yet with connections to the Asian American community and the Chinese student community in the UK, the participants in this forum feel compelled to ask: what makes anti-Asian racism an emotive cause of complex feelings and actions, and how, if at all, may it relate to other race-based justice movements, such as Black Lives Matter, a collective movement that has drawn international students, Chinese and Taiwanese, to participate and to reflect on the significances of race and belonging? How might we identify and decipher the complex meanings of China and Chinese-ness in these COVID-ridden times, in relation to the US, Taiwan, and the Chinese diaspora? In particular, how can we begin to talk about the precarity of Chinese international students in the US and the UK who, while nominally included in the umbrella terms of Asian American and Asian British, may not see themselves as belonging to those categories? What does it mean for such students to take political action against anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia when being political may come with great political costs abroad and at home? How can they find a place in the pan-ethnic framework of anti-Asian hate activism especially in the heat of US-China contention without being prejudged as a Chinese nationalist and therefore dismissed or even suspected? Ultimately, how might we address the inter-racial, inter-Asian, transpacific tensions and fissures within these justice movements and build alliance and solidarity from there?

Below I highlight a few more points that the forum collectively brings to the fore, which can be summarized as follows: how do we identify the root causes of anti-Asian racism activism and offer a compelling analysis that is attentive to both its vision and blind spots? And how might we address the critical dissonances in anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia by focusing on non-citizen migrants?

In her contribution to this forum, Wendy Cheng asks us to identify the global, imperialist and capitalist roots of anti-Asian racism by calling out white supremacy as the root cause of the problem. She specifically argues that white supremacy is “not a thing in itself, but rather what is historically shaped by Western imperialism, Western liberal humanism, and the intertwining of these with capitalism and colonialism.” While white supremacy may express itself in the form of Orientalism, as an othering, dehumanizing discourse, it is more entrenched in the systematic operations of inclusion and exclusion, liberation and domination, as a kind of “racial contract” (Charles Mills 1999) of humanity and citizenship. In contrast, Wen Liu cautions us not to give in to the politics of injury so fast by staying vigilant about the dangers of liberal antiracism that may have been the cause of our problem. As much as Donald Trump is to be blamed for the racism we suffer in an immediate sense, Wen Liu argues that capitalist crisis and imperialist rivalry are what produced a “superior and threatening foreigner” to conceal the internal crises of our societies. While the model minority and the yellow peril images are both racist in nature, the anti-racist claim advocated by Asian American and African American activisms in the US may not adequately address the class divisions in our communities; it may also be used by the PRC for different purposes, to justify its human rights violations in Tibet or Xinjiang for instance. Flair Donglai Shi asks us to acknowledge that anti-Asian racism is in fact fueled by the Sinophobia on a global scale led by the US. As he argues, there is no way to escape anti-Asian racism if we do not directly engage with the problem of Sinophobia in the new Cold War context, while, at the same time, keeping our political differences at bay because the “main struggle is against white supremacy.” In other words, focusing merely on anti-Asian racism misses the kernel of the problem, that is, the West’s fear and anxiety about China’s becoming a global hegemon. The traction that Trump’s racist vitriol garnered speaks volumes about the anti-communist, anti-authoritarian, and anti-globalization angst in Americans, all congealed in the negative imagination of China and Chinese-ness.

Indeed, the “transpacific dissonance” Yihung Liu identifies is clearly at odds with the imagination of a rainbow coalition that defines anti-racist politics in the US. But the memory of a rainbow coalition that marked and shaped the Asian American and Pacific Islander identity since the 1960s also points to the importance of working through differences towards liberation, not the liberation of one group over the other, but the liberation of us all. As Viet Nguyen writes, “This is the only way that an Asian American-Pacific Islander coalition makes sense—pointing the way toward alliances with other groups, from Black Americans to Muslims, Latinos to L.G.B.T.Q. people. Asian Americans are one political identity among the many that must come together for decolonization.” Inspired by such a coalitional legacy, Kun Huang delves into a careful analysis of the PRC Chinese students who become involved in race-based justice movements and who have created diverse and transnational networks to produce knowledge about racism and sexism and to mobilize political action in the US-based Chinese-language culture sphere. But she also indicates that these students’ “inability to fully inhabit and exhibit their political selves further hinder[s] the building and cultivation of activist sociality.” This has to do with the stratification of immigration regimes, as evident in the wide range of immigrant and non-immigrant visas. As a mechanism of selected inclusion, visa status encodes state power in shaping the subjectivity of the migrant as well as its relationship to civic life in which international students and migrant workers are conditionally included yet selectively excluded. For Huang, the assertion of Chinese students in this context is not for the sake of embracing the PRC statism, nor a complaint of negligence. Rather, it is “to broaden an ever-growing community, to become a concrete and vivid member of transnational solidarity,” and to fulfill the promise of the AAPI coalition where non-citizens would also be counted, included, and matter.

This discussion makes evident that we need more than ever an intersectional analysis and coalitional politics to critique and counter the adverse effects of white supremacy and the real effects of imperialism. It is not an easy task, because anti-Asian racism is crisscrossed by multiple factors of history and relations of power, in which inter-Asian conflicts and differences—the Taiwan-China issue for instance—may present themselves as a hindrance to coalition. When people are unsure who the enemy is, it is difficult to form a united front. In this sense, building alliances across dissonance is hard and real work. It requires not only an understanding of each other’s histories and struggles, as Yihung Liu explains, but also a keen sense of what we wish to achieve. We cannot be satisfied with the easy rhetoric of solidarity and empathy without trying to change the capitalist, settler colonial, and racial structures that privilege certain groups and nations over others. In the meantime, we also cannot afford to ignore the great disparities of power and state mechanisms that constitute the transpacific world we live in without an understanding of how geopolitical, ideological, and racial-national divisions have cut into the formations of our subjectivities—as migrant workers, international students, and Asian American or Asian British citizens. We will not resolve our problems all at once by claiming a coalitional identity, nor do “we” actually share the same problems when crossing the Pacific. But acknowledging and knowing the internal fissures is a critical first step, and the openness and willingness to form coalitions is a must. In the wake of the tragic deaths in Atlanta, it is clear that AAPI activism must embrace citizens and noncitizens alike, attend to the political machines that divide, define, and rule us, and hold dear the vision that each life matters. Our analysis and activism must stretch beyond borders to face and rectify the disparities of the world. When vaccines have become “strategic materials” and race-based hatred a symptom of our illness, we need a real change at home and abroad to respond to our pain, anger, and shame.

Chih-ming WANG(王智明)is Associate Research Fellow at the Institute of European and American Studies, and the chief-editor of Router: A Journal of Cultural Studies in Taipei.

— Chih-ming WANG (王智明), editor