Wendy CHENG (鄭昕)

To begin, I want to acknowledge the current grief, anger, and fear of Asian and Asian American communities here in the United States, where I am located.

From March 2020 through March 2021, during the ongoing covid-19 pandemic, there were more than 6,000 reported incidents of anti-Asian hate in the United States, ranging from verbal harassment to physical attacks. Women were 2.2 times more likely to be victims of such incidents, and the elderly have been targeted in particularly tragic ways. Such racist violence peaked on March 16, 2021 with the mass murder of 8 people in Atlanta — 6 of whom were Asian women –by a 21-year-old, white, male evangelical Christian.

After the Atlanta murders, the national and global conversation on anti-Asian racism within the U.S. became mainstream news in a way that it arguably never had before. As such, we — scholars, activists, and writers — may now have rare opportunities to inform and shape the discourse in meaningful ways.

In this moment, I want to suggest a seemingly simple but vital shift. We need to deepen public understanding not only of so-called “anti-Asian hate” but of its roots: yes, white supremacy – but not as a thing in itself, rather, as it has been historically shaped by Western imperialism, Western liberal humanism, and the intertwining of these with capitalism and colonialism.

As philosopher Charles Mills pointed out in his important 1999 book, The Racial Contract, Western Enlightenment thinking arose in history at the same time as European imperialist ventures across the globe and cannot be disentangled from race and empire. In other words, in that configuration of the world order, the idea of the universal human in liberalism was only possible if non-white, non-European “others” were considered not-quite-human, or subhuman.

Despite claims of American exceptionalism, this is the United States’ intellectual and political foundation as well. From the founding of the United States — a nation built upon the simultaneous enslavement of Africans and the genocide and settler-colonial dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands — the ongoing fiction of “liberty and justice for all” was only possible if such groups were categorically not considered to be people under the law. This was established from the beginning, as only white male property-owners qualified to be citizens, and people of African descent were considered to be literally only 3/5 of a person under the law. Later, Asians were categorized as racially “ineligible for citizenship,” and were racially excluded from naturalizing as U.S. citizens until 1943.

The history of Asian American racialization in the U.S. is ideologically and discursively intertwined with a longer history of European orientalism, stemming from French and British colonization of the Arab world in the 18th and 19th centuries and finding form in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Orientalism, as Palestinian American scholar Edward Said elaborated in 1978, is the cultural figuration of the “East” as the “West’s” forever other, a position that justifies domination, exclusion, dispossession, and obliteration. Today, this flexible figuration of an embodied – and emplaced – geopolitical and geographical other continues to function with terrible power as an ongoing ideological justification for U.S. support for the settler-colonial occupation of Palestine, the violent dispossession of Palestinians, and the mass killing of Palestinian people, including children and whole families, by the Israeli state.

However, as Colleen Lye pointed out in her 2005 book America’s Asia, since the late nineteenth century, in American orientalism, “Asiatic racial form” has not functioned merely as the United States’ antipodal other, but also as its proxy, “present[ing] split alternatives between the whole world becoming American and an apocalyptic clash of civilizations.” Nineteenth and early twentieth century Yellow Peril discourse emerged simultaneously with differentiated and often contradictory global geopolitical fears of Japan and China as well as struggles to extract cheap labor from Asian migrants without incorporating them into the U.S. polity. This “ongoing intimacy between Asiatic racial form and the contradictions of U.S. globalism” arguably continues into the present.1

Such orientalist and Yellow Peril logics were deployed by the U.S. state through exclusionary immigration laws, restriction from naturalized citizenship, Japanese American Internment; and in wars in the Philippines — and later, Korea and Vietnam. It was not until after World War II that Asian immigrants were conditionally accepted into the United States. During the Cold War, as scholars such as Cindy I-Fen Cheng have shown, Asian Americans first became the “model minority” whose supposed success and assimilation to white, middle-class norms disproved the existence of racism in the United States. After the Civil Rights Movement, the model minority stereotype became more entrenched as U.S. conservatives sought to dismiss evidential realities of ongoing structural oppression of African Americans and Latinos.

The model minority stereotype, however, depends upon the same racist logic as orientalism — that “Asians” have essential cultural characteristics that can never be detached from their race (for example, that they work hard, value education, and are quiet and politically passive). This stereotype is ahistorical. It obscures 1) the particular historical conditions through which Asian immigrants came to the US after 1965 (for example, prioritizing in law the entry of students and professionals in science, technology, engineering, and medicine fields as well as wealthy businesspeople); and 2) the diversity of Asian and Asian American communities (for example, say, Southeast Asian communities — particularly Hmong, Lao, and Cambodian — the majority of whom came as war refugees, as compared to Taiwanese communities, who tend to be wealthier and more privileged because of their own conditions of migration). In other words, it ignores the fundamental role of the state in shaping heterogeneous Asian peoples’ parameters of existence in the United States.

Because the model minority characterization seems to portray positive qualities, however, many Asian Americans themselves internalize the stereotype. For example, 2020 presidential candidate and current New York city mayoral candidate, Taiwanese American Andrew Yang, embraced it by characterizing himself as “an Asian guy who’s good at math” and adopting “MATH” as a campaign slogan. Later on, early in the pandemic, Yang wrote that Asian Americans could counter anti-Asian racism by working hard to prove how American they really are.

Regardless of intent, Asian Americans’ embrace of model minority identities ultimately supports white supremacist logic and worldviews. Such an identification perpetuates racial-economic tropes of human value. It encourages Asian American exceptionalism: the idea that we are somehow different or better than other minoritized racial groups in the United States. This identification reproduces a dominant ideology of the United States as a fair and neutral society, while obscuring or even excusing the genocidal tendencies of white supremacy as intertwined with colonial and capitalist world systems. And, perhaps most germane to this forum, it predicates value on the capacity for assimilability – or assumed desire to assimilate – to the nation, such as it is.

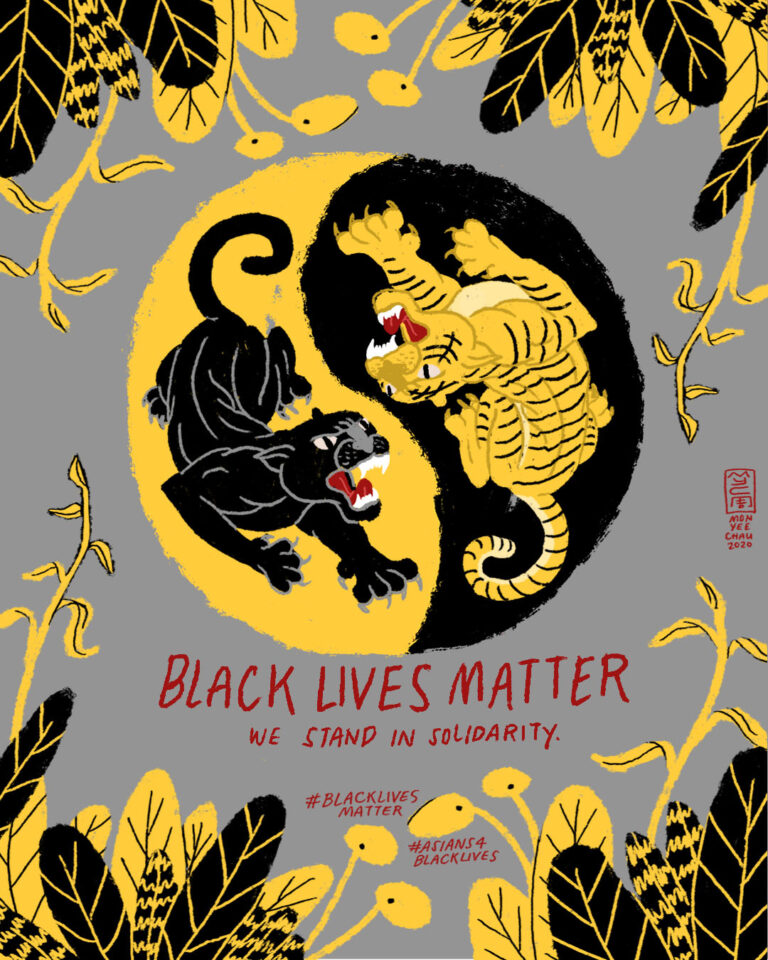

To effectively counter anti-Asian racism, Asians and Asian Americans in the United States must insistently name, analyze, and expose the global, imperialist, and capitalist roots of white supremacy, as well as build intra-ethnic, cross-racial, transnational, and translocal coalitions to refuse their deadly logics. Currently, in the US, together with the surge in anti-Asian violence, we are seeing another rise in child migrants detained by the U.S. government after crossing the southern border. Abolitionist attempts to defund the police continue after the brutal public murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in May 2020 reignited the Black Lives Matter Movement on a global level. The steep rise in Sinophobia occasioned by the enflamed racism of the covid-19 pandemic will only continue as China continues to challenge the United States’ global dominance. We need these analyses and coalitions – as difficult and uncomfortable as they might be – now more than ever.

To end with a bit of hope: one of the scholarly fields that shaped my worldview is Asian American studies. Asian American studies in the US came directly out of Third World Left social movements that built common cause across oppressed racial groups and Indigenous peoples and opposed imperialism, colonialism, and white supremacy. In terms of building knowledge, power, and platforms, Asians and Asian Americans are in a much different place than they were 50 years ago. Despite the violence and ongoing crises of life in the US today, over a year into the covid-19 pandemic, I see colleagues, friends, and organizers – both Asian and non-Asian – doing powerful work in media and communities to educate, inform, and build relationships. I see a greater plenitude of voices and media in diasporic Asian communities — for example, in the immediate aftermath of the Atlanta murders, Korean newspapers in Atlanta were the first to report on the murdered Asian women in ways that insisted on affirming their humanity, and they immediately called out the white Atlanta police chief for excusing the white killer’s actions as the product of “a bad day.” And Korean American pastors in Atlanta openly called for anti-racist action within Asian American communities as well as systemic change. Newly created diasporic and transnational platforms are nurturing leftist, “anti-nationalist” communities of dialogue that amplify fresh solidarities while refusing to gloss over real differences.

Like the World War II mass incarceration of Japanese Americans, the U.S. war in Vietnam, the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, and the Los Angeles Uprising of 1992, now is a time of political awakening for Asians and Asian Americans.

What world will we choose to wake up into? What world do we want to participate in building?

Wendy CHENG(鄭昕)is Associate Professor of American Studies, and Chair of the Department of American Studies at Scripps College.

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.