Darren Byler, Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia

Since its founding, the revolutionary ethos of the People’s Republic of China has been framed by discourses of liberation and a rhetoric of anti-imperialist solidarity. The founding of the People’s Republic stood in opposition to a legacy of European and Japanese imperialism and the entrenched inequalities of Qing and Republican-era modernism. Like the Soviet Union, China positioned itself as a postcolonial state. But despite these claims and efforts by Maoist leaders to promote multinational solidarity and guard against Han chauvinism, the Han-dominated party-state nevertheless inherited and intensified control over the ancestral lands of the largest non-Chinese speaking groups in the country, the Tibetans and the Uyghurs. This led to the establishment of a settler state in Inner Asia during the Mao era, and, as China transitioned into a central node of global capitalism in the 1980s and 1990s, this Inner Asian project has evolved to include more and more of the features of an internal settler colonialism. At the same time, the enduring legacy of Mao era “settler socialism,” a term that I borrow from the work of my colleague Grace H. Zhou,1 has served to further elide the contemporary autonomy and knowledge claims of Uyghurs and other frontier peoples.

The People’s Republic of China was founded on the imperial legacy of the late Qing Empire. While aspects of the early Qing empire were conciliatory and coalition-focused toward Inner Asian peoples, the People’s Republic also inherited a more recent, largely Han-led, Qing legacy of mass violence carried out by Zou Zangtang’s armies in the 1870s, a Confucian education-centered capture of Turkic institutions, and the mass deportations and settlements of both Turkic and Han people in the region. So as the national liberation campaign was launched by the PRC in the 1950s with the goal of indigenizing Communist Party state systems, administrative structures, and adapting existing institutions such as schools, media, and communal authority structures to promote the core values of the Party these, often unacknowledged, legacies of expropriation and domination played a role in the way Uyghurs were forced, at least in some instances, to receive their liberation.

The defensive state building politics of the new People’s Republic also mitigated against Uyghur autonomous liberation. A 1949 conversation between Joseph Stalin and Chinese Communist vice chairman Liu Shaoqi, where Stalin describes the need for Chinese to “occupy” Xinjiang in order to secure oil and cotton resources for China in reaction to British imperialism is particularly instructive in this regard. As Stalin put it:

One should not put off occupation of Xinjiang, because a delay may lead to the interference by the English in the affairs of Xinjiang. They can activate the Muslims, including the Indian ones, to continue the civil war against the communists, which is undesirable, for there are large deposits of oil and cotton in Xinjiang, which China needs badly. The Chinese population in Xinjiang does not exceed 5 percent, after taking Xinjiang one should bring the percentage of the Chinese population to 30 percent by means of resettling the Chinese for all-sided development of this huge and rich region and for strengthening China’s border protection. In general, in the interests of strengthening the defense of China one should populate all the border regions by the Chinese.

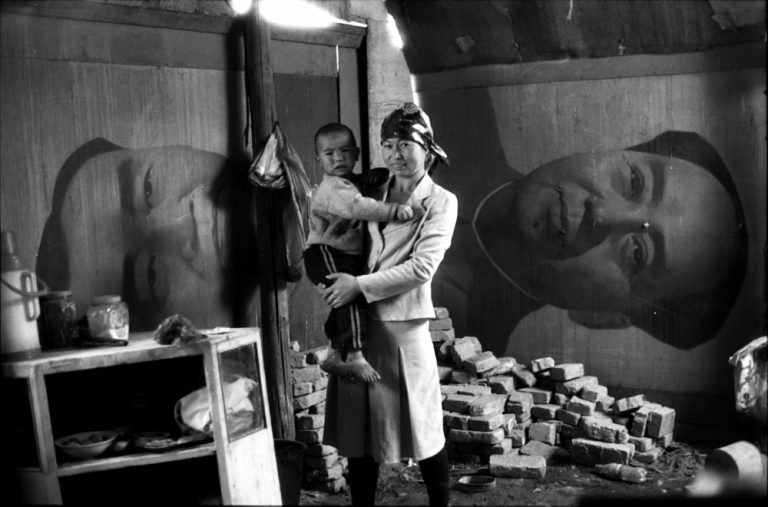

So while the People’s Republic did strive to institutionalize a Uyghur socialism, from the very beginning, the resources of Uyghur and Kazakh ancestral lands now belonged to the party-state and were subordinated to the demands of the majority-led revolution. As an archipelago of Han-led agricultural and military colonies was established across the region in the 1950s the settlement of those lands by decommissioned soldiers and others established the occupation that Stalin invoked. By the end of the decade, many Uyghur and Kazakh carriers of traditional knowledge—glossed as counterrevolutionary superstition, or as “local nationalism”—had been removed from positions of power in community leadership and a new focus on Han-centric scientific modernization came to the fore. This is the period in which Uyghur “native” or yerlik knowledge, a term I will return to in the second half of this essay, came to be conflated with a “backwardness” in need of the “advanced” or scientific civilization of the Han majority.

The enduring presence of imperialist aspects in China’s rule of Inner Asia is what leads me and a number of other scholars committed to decolonization and antiracism to think in parallel with Grace Zhou about 1950s to 1980s Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia and Central Asia as spaces of settler socialism. This framing, which I view as both an acknowledgement of the unfulfilled promise of Maoist revolution and an acknowledgment of the emergent occupation, domination and dispossession brought about by the same process, is a way of naming the particular forms of twentieth century Soviet and Chinese colonial projects.

Settler socialism is perhaps best understood as a type of “subimperialism” or subcolonialism that responds to what Natasha Kaul refers to as a “moral wound” of past colonization or semi-colonization often narrated as a “century of humiliation” in contemporary Chinese state-narrated history. Subcolonialism, what I take to mean the colonial actions taken by the formerly colonized, is expressed in this case through the imposed development and intensified colonization of China’s Inner Asian frontier (particularly during China’s post-Mao embrace of global capital) and justified through the logic of the wound. This logic leads to the conclusion that because China’s body politic was so badly wounded by its experience with colonialism, it’s occupation, domination and dispossession of peripheral peoples is not only justified but is itself an expression of anti-imperialist care.

To be sure, there is in fact some truth to Chinese settler self-valorization. The politics of recognition inherent to settler socialism were more progressive than other colonial politics of recognition. One primary example of this is the way that the effort of indigenizing state systems and pedagogy allowed unassimilated minorities such as Tibetans, Uyghurs and Kazakhs to protect their own languages, and, though filtered through the state apparatus, expand knowledge production in those languages. This “permitted difference,” as Lousia Schein frames it, did provide peoples with the institutions to preserve some aspects of their epistemic difference. Quite unlike Indigenous peoples in North America in the same period, these groups developed their own curriculums, literatures, music, arts, and traditional medicine schools, even as they were subordinated to Chinese knowledge and scientific modernism. This is part of the reason why North American Red Power movements, in the midst of “the sixties scoop” in which thousands of First Nations children were forcibly taken to English-medium, often Christian, residential schools, were enamored with Maoist politics. Similarly, groups like the Ainu, who at that point were unrecognized by the Japanese state, saw Chinese national liberation policies as ideal.

So, to be clear, settler socialism, before it turned to the settler capitalism of the post-Mao era which I write about in my book Terror Capitalism, was in some ways a different form of military and settler occupation than Euro-American or Japanese varieties. One could even argue that because it was intended as a liberation, it should be viewed as qualitatively different from other colonialisms, or, as some might put it not a colonialism at all and instead as an expression of a largely laudatory “pluralist universalism.” Such apologists, likewise point out that among Uyghurs and Tibetans, a small elite class of Chinese-speaking cadres emerged in the 1960s and participated as collaborators in the settler socialist project. Taking this small number of urban Chinese speakers as normative, they fail to note that these elites embodied many of the features of ambivalent colonial mimicry that Homi Bhabha discusses in relation to the role of collaborators in British colonialism. This Chinese language centered approach, and the failure to think from subaltern perspectives, is precisely the problem with such approaches. By taking “the nuanced” position of the colonial collaborator as normative, and “disrupting the settler-colonized binary” by accepting the statist justification of the settler socialist project largely at face value without first examining and assessing its broad structural harms, such scholarship reproduces colonial claims. In doing so it erases the normative, lived experiences of large majorities of Uyghurs and Tibetans, silencing the voices of those most harmed by settler socialism.

To escape the cul-de-sac of this Han-centric and methodological nationalist apology for settler socialism, the question of intent must of course be problematized by comparative historiography and the careful examination of Inner Asian experiences. Many imperialists have justified their actions through discourses of Christian or racial salvation and doctrines of discovery, or the gifts of education, development and democratic freedom. To critically understand how such projects are received, and not reproduce their logics, it is important to examine the experiences of those who are affected by them. And this brings me to the question of the way indigeneity is elided by settler socialist multiculturalist projects. Because of the partiality of settler socialism as a colonial project—namely the way state structures were partially indigenized, but still dominated by Han-centric scientific modernism, state media discursive control, and militarized occupation that claimed to be post-colonial—it has been difficult for native peoples to locate themselves in broader indigenous struggles.

In the broadest sense the term Indigenous—whether as a descriptor or as an upper-case “I” political identity—is contested in China because it is seen as a concept that challenges the sovereignty of the Chinese state and the right of the majority, glossed as “the people,” to possess the ancestral lands of minorities. The 1990s discourse of anti-“separatism” and, in the 2000s, the anti-Muslim rhetoric and technologies of “counterterrorism,” which were attached to Uyghurs and Kazakhs who were perceived to be overly attached to their particularistic identities, have further cemented the perception that “indigeneity” is a negative signifier. But, to borrow a phrase from Elizabeth Povinelli’s framing of liberal multiculturalism, there is something even more “cunning” about China’s politics of nationality recognition. After decades of immersion in settler socialism and capitalism, many elite Uyghurs have internalized Han-centered discourses of civilizational advancement and view their lack of national self-determination and attachment to land-based traditions as a sign of lack inherent in their own social modernity. For them, the term Indigenous has come to signify a so-called primitive “backwardness” that state discourses of both settler socialism and settler capitalism have identified with their pre-“liberation” societies. For such elites, state modernity and scientific knowledge are framed as the only ideals worth striving for. And as a result of both state pressures against self-authorized identifications, and internalized antipathy toward indigenous framings, elites from Tibetan and Uyghur groups, even in the relative protection of exile, have largely not sought to position themselves within internationalist Indigenous movements.

However, despite these reasons for not identifying as Indigenous, increasingly a younger generation of leftist Inner Asian scholars have begun to take up Indigeneity as a political identity that responds to global decolonial movements. They recognize that as their lands and difference become sites of increased economic theft, state authorities and majority populations have come to recognize minority claims to difference itself as a deficit and threat. This in turn has produced a deeper racialization of their ethnic difference. And as a result comparative scholarship on indigeneity, decolonization, antiracism, and internationalist abolition have given these scholars new ways of understanding storytelling and oral tradition, sacred landscapes, and epistemic violence, and pushed them to unlearn assumptions they were taught concerning development and settler socialism. It has also given them ways of seeing both the utility and failure of state-centered approaches to identity; and has galvanized an emergent decolonial critique of the methodological nationalism—the Chinese exceptionalism that emerges from the logic of the wound—that pervades so much of China Studies.

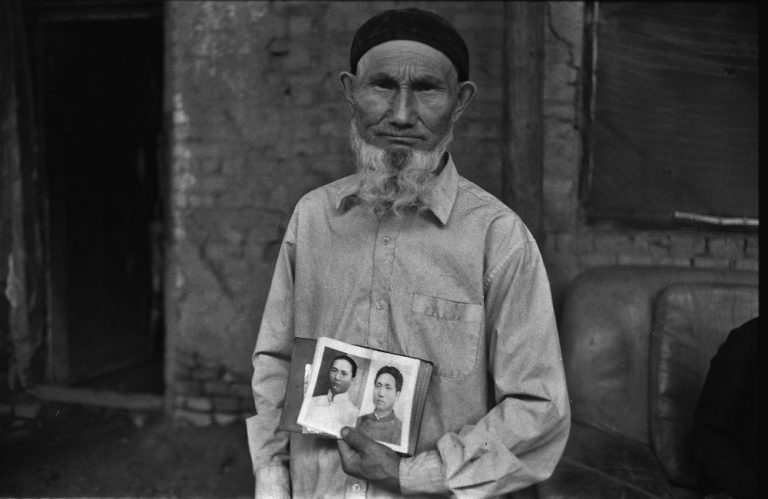

The work of this emergent generation of scholars—Dawa Lokyitsang (Tibetan), Anonymous (Uyghur), Guldana Salimjan (Kazakh) and others, has pushed me to think about Uyghur identifications as a particular expression of indigeneity that is both inside and outside internationalist decolonial movements. As I have shown elsewhere, in my fieldwork in Northwest China I found that the way Uyghurs embodied traditional knowledge through heritage trades, cultural traditions, and mutual aid provided them with a way of refusing structural violence. It gave them a feeling of rootedness in deep yet changing tradition that pre-existed modern state form. Following the hand-lettered signs that I observed Uyghur farmers use to signal the authenticity of their traditional products and services, in my book Terror Capitalism I develop the Uyghur term yerlik or “of the land” as a positive claim to an upper-case “N” Native identity. By claiming this as a uniquely Uyghur indigeneity, Uyghurs are signaling that Uyghur identifications should be viewed as proximate to the claims of Indigenous peoples elsewhere. Insisting, at least for now, on using the term yerlik or Native, also recognizes that the term Indigenous is the subject of a great deal of current debate among diaspora Uyghurs, even as there is now near unanimity among the same group in characterizing state violence toward them as a structure of colonization carried out by a settler capitalist Party-State. This discussion, along with the unpacking of the legacies of settler socialism, is just now beginning to unfold. But even in its nascent form, it is sparking conversations across Sinophone Studies and Critical Indigenous Studies, and establishing new solidarities with decolonial, abolitionist, and autonomous movements across Asia, the Middle East, and the still-colonial metropoles of EuroAmerica.