ann-elise lewallen, University of Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia

“June 14, 1973”

When that first stake was hammered into the soil, the soil of Usu Bay,

That moment,

The earth howled fiercely

Men could you not hear it?

The bellowing…

The ocean, feeling the earth’s pain

Recollecting this deep lament,

Shivered with anger

Imperial radio NHK, its announcer at the site, screaming hysterically over the airwaves, “The power plant is urgently needed, Now. Hokkaido’s electricity will not suffice!”

Energy for what?

For the corporates? Or for NHK?

For the Prefectural office? Or to power the SDF base? Or for the pref. police?

Who lacks energy?

This history,

repeats

Callously it reveals itself again

Lacking, any capacity or technique for resisting, defenseless,

This earth

Aiming toward it,

As capitalists

As invaders

Without shame,

Without memory of this history,

The stake is driven in1

The stake that pierced the earth above anchored one of Hokkaido’s earliest energy development projects: southern Hokkaido’s Date Thermal Power Station, ultimately completed in 1978. Funkawan had nourished the Indigenous Ainu of Yaun Mosir (present-day Hokkaido) for centuries, and likely millennia. Well into the mid-20th century Ainu fishers were sustained by the bounty of scallops, flounder, octopus and seaweeds like wakame, kelp, nori, and the occasional yori-kujira (stranded whale), offered up by the bay’s repun kamuy (guardian of the ocean). Funkawan (the bay neighboring Usu-Date) also supported one of Hokkaido’s most productive fisheries. Usu was located on the western flank of Hokkaido’s industrial heartland: Muroran fired the engines of settler modernity with heavy industries like Japan Steel Works (ca. 1907), and neighboring Tomakomai had expanded its manufacturing and shipping capacity throughout the 20th century. Rushing to multiply its postwar industrial production, the central government pushed Hokkaido Electric Power Company (HEPCO) to expand energy production. In early 1970, HEPCO proposed a 250 MW oil-fired power plant and quickly ramped this up to 700 MW. As I document in this struggle, the settler state’s alienation of Hokkaido’s waterways and kamuy (multispecies relations) from Ainu helped entrench settler colonial routes into ancestral Ainu lands through energy colonialism.

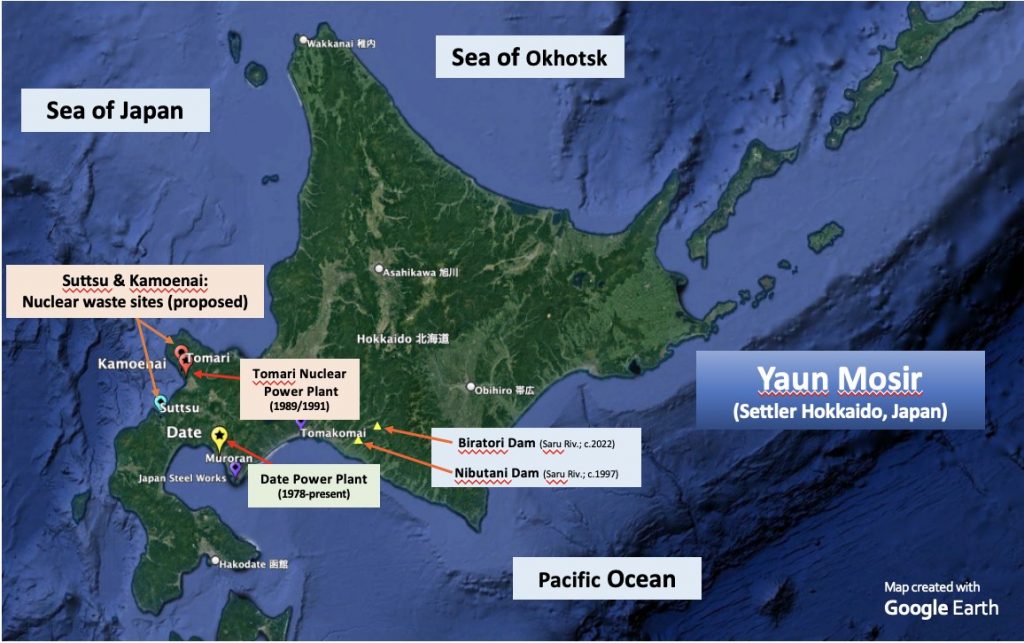

Living with the residue of Japan’s worst nuclear catastrophe, the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, Indigenous Ainu lands in southern Hokkaido now face old and new forms of energy colonialism. The legacy of the Date Power Plant struggle has a long arc which continues to fuel energy and resource colonialism. Ainu in Hokkaido did not sign any treaties with the Meiji government of Japan nor receive any payments when the government unilaterally annexed the island in 1869, adding 20% of mineral, forests, and arable wealth to Japan’s total land mass. Ainu have never enjoyed Indigenous sovereignty, even after Japan signed the 2019 New Ainu Law, officially recognizing Ainu as Japan’s Indigenous peoples, yet refusing sovereign legal or political status under this law. Instead, both the government and Japanese publics have classified Ainu as a “separate and inferior race,” and often as a “vanishing race.” In this way, state and private entities have long deployed racialization to shift the discursive register and disguise the settler colonial project of seizing Hokkaido’s land, minerals, air, water, and now its subterranean spaces. By narrating the struggle over Date’s fisheries, here I expose how energy (and resource) colonialism animate and legitimize colonial governance.

Settler energy extraction projects (like Date) today enjoy support from local governments across Hokkaido who are vying to host the nation’s most toxic nuclear waste. Japan’s central government proposed a Deep Geological Repository to house the nation’s High Level Nuclear waste in 2020, and two Hokkaido towns (Suttsu and Kamoenai-mura) have volunteered for the project’s first stage. “Poisons were made with no knowledge of how to erase them,” observed Ainu elder and poet Ukaji Shizue in a recent teach-in. “These 50 years, 100 years, we humans laid waste to the land and prioritized human economic growth, treating the earth so badly. And now here in Hokkaido nuclear plants have been built, and for nuclear waste, this survey to choose the Final Nuclear Waste site in our land is moving forward. The bill for these poisons we created but cannot erase is coming to all people, we will face much sadness,” she continued.

In the 1970s, the 700 MW power plant was the largest of its kind for the region and was intended to fuel the region’s growth as Japan’s northern industrial hub. What Ainu fishers knew of the ocean ecosystem and its delicate balance with plankton and other tiny species, sprang from their Indigenous epistemologies and daily routines of living with these ecosystems. Plankton’s survival was not a biological enigma; the Usu fishers knew that its survival was inextricably bound with their own. Today this reciprocal ethic of care has come to be known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge. TEK entails managing the flora, fauna, and waterways of one’s local ecosystem as an extended kin network, the survival of which is entwined with one’s own. Centuries of assimilation policies and attempts to erase Ainu management systems mean that few recognize the place-based and ancestrally honored system of ocean-management as TEK. After all, ethnic Japanese (wajin) fishers had laid the infrastructure for the earliest settler extraction by enslaving Ainu as corvee labor in the 17th-19th century “contract fisheries,” which obliterated Hokkaido’s herring stocks. But the Usu and Date fishers had cultivated sustainable resource systems, complex bio-feedback mechanisms that would inevitably collapse, they knew, if the plant and its sulfur dioxide ecosystem were introduced into the human-marine life balance that the fishers had sustained up until the mid-1970s.

Usu and Date fisheries unions had given permission for the thermal plant’s construction until they realized what it meant for the marine ecosystem. To understand its impact, they set up citizen study groups to examine how the chemical effluents would bio-accumulate in the bodies of fish. Using citizen science and dialoguing with communities in southern Japan who had mobilized against local oil-combustion plants, the fishers began to understand that heated wastewater from the plants would raise the ocean temperature. Heat-sensitive biota like plankton would perish and seaweed growth would suffer thus driving key fisheries like flounder and scallops away. Pollution systems, they learned, overlapped. First, heavy oil combustion would release sulfur dioxide into the ocean and airways; and second, heated water from the plant’s outtake pipes would elevate ocean temperatures between 8-10 degrees Celsius. For humans, sulfur dioxide would lead to asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema. In short, their livelihood and key food source hung in the balance. As leader Shiiyama Iwao argued, “As fishers we depend on a living ocean, an ocean that feeds us protein and provides our livelihood. If the ocean ecosystem is ruined, we will be forced to depend on import[ed foods], and we fishers will be out of a job.”

Following HEPCO’s power plant proposal, Ainu fishers joined with farmers, teachers, doctors, and other residents to resist the proposed development. After months of heated protest and protracted court battles, HEPCO and local boosters prevailed in constructing the plant, which now feeds between 15-17% of Hokkaido’s electrical grid, since the region’s nuclear plants have been shut down in the decade since the Fukushima meltdowns.

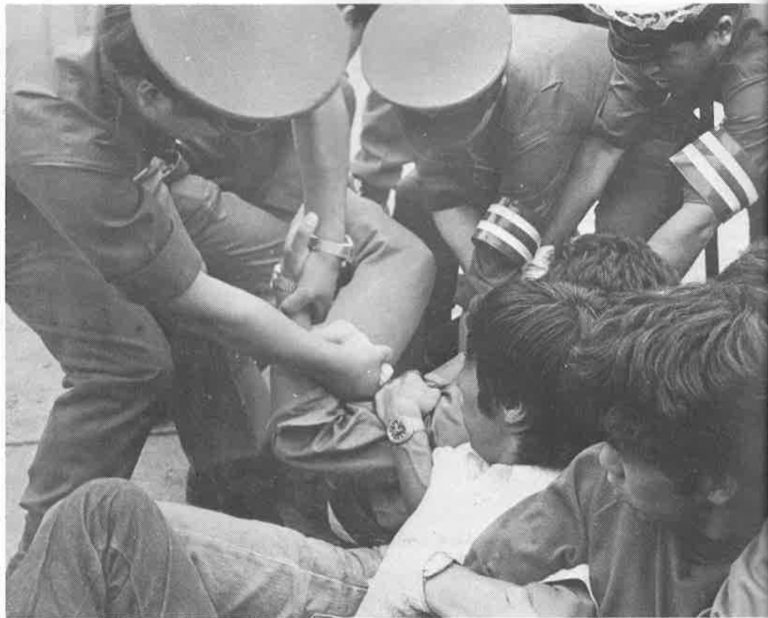

Dondari Kondari. Slapdash, haphazard, sloppy. Usu and Date fishers had a catchall vernacular term for poorly-done work: dondari kondari. The fishers described the power plant construction plan as nothing less than slapdash, anticipating that it would wreak economic chaos in their lives. Against stiff opposition, plant construction was approved in 1972. This approval galvanized the opposition triggering a lawsuit to block plant construction. This “Environmental Rights” case, as it became known, was rooted in the right to enjoy a favorable environment, expressed in the right to life, liberty, and happiness (Article 13), and the right to personal security (Article 35). Until that day in June 1973, when HEPCO ultimately drove its construction stakes into the ground, the fishers, farmers and others blocked construction vehicles with their bodies. On June 14, HEPCO trucked in 500 self-defense troops and 300 plainclothes police. The Ainu fishers and supporters staged a massive sit-in, blocking cement mixers and construction vehicles. Police dragged civil disobedients from the equipment, and HEPCO began filling in the bay.

“This power plant is a plankton death machine.” Usu youth leader Toma Kazumi pointed out, “For us fishers who draw livelihoods from the ocean, this is a matter of life and death.” Even while some accounts reported the Usu activists downplayed their Ainu ancestry, some observers portrayed the fight to block the plant as “an Ainu problem.” As the battle escalated in 1973, the independent Ainu-run newspaper, Anutari Aynu, hosted a roundtable of Ainu leaders to consider how the plant might impact the fisheries. After initially debating the balance between ecosystem and livelihood, they turned to the plant’s disproportionate impact on Ainu fishers. Utari Asociation leader Sunagawa Nobukichi explained, “We are not the Ainu of yesterday, those Ainu who were deceived by Shamo, in the past. Some may say that HEPCO should be kowtowed to as our superior…. We Ainu are different today…A bad proposal is a bad proposal no matter who proposes it.” Later Sunagawa opined, “For us, it’s not a question of Ainu vs. wajin: 49 Ainu are opposed, and 20 Ainu support the project… Whether you’re Ainu or Shamo, when you begin to understand about the pollution, each person will come to oppose the project on their own.” Meanwhile, the “environmental rights” lawsuit ended in defeat in 1980, and plant construction was completed in 1978. As anticipated by the opposition, fisheries’ data for Iburi (Date-Usu region) demonstrate that between 1975-1982 (after the plant’s construction) the Date-Usu fishery collapsed: shellfish production fell 73%, and overall fisheries catch decreased by 54%.

Ainu and Kamuy, An Ethic of Care

As Totsuka Miwako’s poem suggests, Usu and Date fisher’s opposition to the power plant, and more broadly to energy colonialism in their ancestral land, emerged from a sustained relationship with the ocean and terrestrial beings in both. It was also rooted in day-to-day knowledge of the need to balance ecosystem with human livelihood requirements, with humans depending on the ecosystem for their livelihood, both as direct consumers and as producers for the marketplace. This basic understanding, fundamental to life itself, drove the fishermen to place their bodies on the line and fight for an earth which was, in Totsuka’s words, “defenseless” against the construction stakes. Ainu fishers from Date and Usu who were among the staunchest land defenders, nevertheless, did not openly emphasize their Ainu ancestry. Structural racism and stigma continued to be affixed to Ainu bodies during the 1970s, which made it difficult to embrace their Ainu ethnicity. This group saw themselves as fishers first, identifying strongly as primary laborers, dependent on healthy ocean relations. They shared a deep horizontal bond with other primary laborers –wajin fishers and farmers. Many of the Anutari Aynu panelists also positioned themselves as primary laborers: procuring fish and marine products for their own livelihood, first, and secondly for the marketplace. In this way, “livelihood” emerged from one’s basic needs to generate calories and nourish one’s family, and therein a recognition that failure to care for the oceans and the kamuy of the oceans would mean failure to procure basic nourishment for one’s own family. This understanding and ancestral model for the right relationship with the kamuy translates into an ethic of care, and a moral posture, to ensure that this ethic of caring for all of the unseen beings under the ocean would be implemented in fisheries’ policies to ensure long-term benefit from the ocean. Ainu leader Sengoku Masashi ended with, “What makes our struggle strong is that we Utari (brethren)are fighting to protect our fishing habitat; and the fact that we are doing the right thing gives us confidence…we have been forced to radicalize because our elected leaders refuse to listen to our concerns, and thus we have no choice but to put our lives on the line, fighting for our very survival.” Ainu-kamuy (human-multispecies) relations thus hinge upon acting out this ethic of care, for example, strapping one’s body to a bulldozer as an ocean defender.

There is yet another unexpected legacy of the Date Struggle which implicates energy colonialism. In the aftermath of Japan’s 3.11 triple meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi, Japan must examine whether and how nuclear power can constitute a just energy source or even a viable transitional option. Date has now emerged as a key source of energy production for the region after Hokkaido’s three nuclear reactor units at Tomari were placed on indefinite shutdown in 2012 due to the discovery of fault lines inside the plant’s campus. Prior to Fukushima’s accident, Date only provided 4.4% of Hokkaido’s total power supply (2004). Yet today, Date supplies nearly 17% of HEPCO’s total output, alongside five other thermal plants, together generating roughly 63% of HEPCO’s total. Date thus fulfills an important role by generating and feeding electricity to the grid in Hokkaido. Far from its role as a flashpoint for Ainu liberation struggles, now Date signifies unresolved questions around fossil fuels and our continued dependence on them when nuclear power fails and other alternatives have not yet been scaled up.

ann-elise lewallen is an engaged scholar and anthropologist of Pacific and Asian Studies at the University of Victoria, where she resides as a guest on the lands of Lək̓ʷəŋən, Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples. Sheis author of The Fabric of Indigeneity: Ainu Identity, Gender, and Settler Colonialism in Japan and co-editor of Beyond Ainu Studies: Changing Academic and Public Perceptions. Her current work focuses on Indigenous Land relations, decolonial mapping, and energy infrastructures in Japan and India.

Works Cited

Anutari Aynu Editorial Board. Anutari Aynu: Warera Ningen 1973 (Volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, 14).

Date Saiban ni Katte Morau Kai. 1974. Dondari Kondari Date Karyoku. Sapporo: Sōei Shuppan.

“Kankyōken no 10-nen, Date Kankyōkensoshō Saiban ni atatte.” Sekai 1980: 11 (Iwanami Shinsho).

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.