The essays collected in this special issue challenge the framework of a “new Cold War” between the US and China in historical and contemporary perspective and evaluate the antagonisms in the context of the current global capitalist economy.

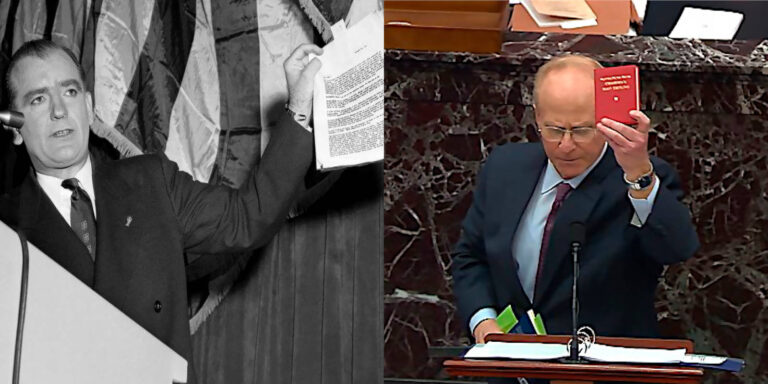

During the February impeachment trial of Donald J. Trump, performed on the floor of the United States Senate, David Schoen, the nth-hour rent-a-lawyer hired by the former President to defend him, brandished in one hand Mao’s “Little Red Book” while declaiming that the proceedings were a sham, an unconstitutional partisan attack motivated by hatred and lust. (dailymail.co.uk, 10 Feb 2021, by Geoff Earle) This vignette evokes the old Cold War while also suggesting that we have exited that era and perhaps entered a new one. …

Let us recall: in the old Cold War, Mao’s Little Red Book actually signified something. Waved all over China by passionate youths, it conjured a sense of anti-capitalist revolutionary fervor; wherever it traveled – to France, to Tanzania, and elsewhere – the Little Red Book was a potent symbol of revolt against the establishment of a single global capitalist order. It would have been too incendiary as a “spiritual atom bomb” to bring onto the US Senate Floor. Indeed, some of the US’s proclaimed major internal enemies of that time, such as the Black Panthers – surveilled by the very reviled alphabet agencies that are now burnishing their credibility for defending “our” democracy against the January 6th mob – were deriving extraordinarily radical practical social and political lessons from Mao’s Little Red Book and Chinese revolutionary practice (e.g. building community kitchens, neighborhood medical clinics, professing gender equity, race- and history-identification with colonized peoples resisting American/imperialist occupation, among others). The Panthers were also selling on Oakland street corners endless numbers of Little Red Books, obtained for free from communist-friendly organizations, to subsidize their community organizing and anti-colonial revolutionary movement. The old Cold War, as Dai Jinhua reminds us in her essay, was not merely a superpower contest, it was a global division that would not take the universalization of capitalist relations for granted. By contrast, today, at the dawn of what is being called a new cold war, capitalism is our global present and Mao’s Little Red Book only can be used as a startling visual prop in “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” It has become an empty symbolic, perhaps only scaring some of the straw men roaming the Capital searching endlessly for some courage or conviction.

A small curiosity: where did Schoen get that book? Was it hanging out on his shelf at home or at the office? Was he or an aide of his once in a university class – such as one of ours? – in which Mao/modern China was a topic of learning? Or, did Schoen or some lackey have Amazon Prime rush him overnight a plastic knockoff so he could emulate the Joe McCarthy Wheeling moment on the Senate floor? When is a prop just a prop? Is Mao a desire or a fetish?

The impeachment trial in February 2021 was organized around Trump’s culpability for the incitement of the violent uprising of January 6, the attempt to stage a coup against the procedural validation of the legitimacy of president-elect Joe Biden. As Josiah Colt, who sat in VP Mike Pence’s chair in the Capitol on that fateful day, announced on his Facebook page, “It’s time to fight for the freedom of this country [USA] from getting bulldozed by the domestic terrorists in office pushing Chinese communist agendas and ideology while stripping our freedoms away one by one.” (Cited from Colt’s FB page by www.eastidahonews.com, published at 7pm 1/7/21/updated at 7:16pm 1/7/21).

In light of Schoen, Colt and others, we can ask: how is it plausible in today’s world to accuse neoliberal Democrats and their Republican enablers in the United States Congress of “pushing Chinese communist agendas and ideology”? What is the through line that allows Colt and Schoen to parade Chinese communism/ Maoism/Marx as the external and internal enemy today? What ghostly haunting makes this possible?

While we would suggest that no amount of somersaulting would make this a plausible position in a rational world—Gustavo Oliveira’s essay on Brazil and Bolsonaro in this collection masterfully articulates this point—nevertheless we must take seriously that this form of fantastical ideation is a fragment of a thought experiment that evidently has escaped the right-wing think tank laboratory in which it was hatched and has become toxically virulent in widening sectors of the far-right, middle-right, mild-right, liberal-right, and even some places on the so-called “left” in American and other societies. We naturally cannot address what might lead particular people to believe, mouth, or performatively espouse these kinds of fantastical non-sequiturs as if they corresponded to something real. However, in the series of short essays collected here, we invited a selection of scholars to think about what a “new cold war” (between the US and the PRC) in rhetoric, thinking, and practice might mean for our contemporary world, or even whether such a designation is adequate to the moment. In their analyses we might begin to find some ways to address our current global crisis.

*****

If we are truly facing the prospect of a “new” Cold War, then maybe the first question we need to ask is what makes the present situation different (or similar) to the “old” Cold War. References to the Little Red Book, Maoist Chinese Communist plots, devious ideological implants, and fear of a communist autocracy purportedly setting in motion some form of “domino” effect could lead us easily to assume that this is simply another case of something appearing “first as tragedy then as farce.” And to be sure there is plenty farcical in the current discourse on “China,” as the coup attempt and Trump impeachment trial exemplify.

Yet, when the rhetoric of war (cold or hot) is so universally mobilized and shared not only among think tanks of various political persuasions but in media discourse and public opinion at large, it seems to be a sign that we are not in the realm (only) of farce. Rather a new Cold War rhetoric has produced and is producing still and anew real consequences: visa bans, trade restrictions that disproportionately damage the prospects of laboring peoples for a livelihood, disruption of collaborative scholarly and organizing efforts, hunts for concealed spies and double agents under cover of the “China Initiative” as taken up by Universities such as our own, and, very ominously in the US and around Europe, a significant increase in instances of everyday and at times violent anti-Asian racism, including the recent mass shootings of Asian working women in Atlanta, Georgia. In Taiwan, as Brian Hioe shows in his essay, this rhetoric has led to increasing incidents of military flyovers and the likelihood of a precipitating casus belli, even while in Hong Kong, as Laikwan Pang analyzes, the new Cold War has produced the global city of Hong Kong as a precarious tinder-box site of protest, police hostility, state repression, and speculative aggression. In this complex context, (old) Cold War symbols and tropes as well as much older anti-Asian racist vocabulary and practices (none of it ever actually went away) are redeployed and repurposed to make a case for contemporary confrontation with China/Chinese/Asians. The potential for actual hot confrontation might appear far-fetched, but the high temperature of rhetoric has serious real-world consequences.

As certain reminiscent epithets of anti-Asianism accompanied by anti-communist political orientations are being bandied about as ways to signal or install a desired neo-fascist prescriptive national and social future (in parts of the US, in Brazil, in other places as well), we must recognize that the material conditions in which these apparent continuities of politics and rhetoric are embedded have changed utterly. Joyce Mao recalls in her contribution that the old Cold War was based in China’s non-capitalist present and what she calls an economic epistemology that equated China’s yellow-communist psychosis with naturalized white-American capitalist supremacy. Clearly, today the terrain has shifted. The material difference is most evident when we take into account the past forty years of China’s economic expansion domestically – thus, the absolute size of the Chinese economy in the global economy – and the past twenty or more years of China’s outward facing support for globalization – thus, the ways in which China, as an economy and geopolitical entity, functions in the world as hinge and glue. The intertwining of China and the world has never been tighter or more central to continuing the exploitative relations of capitalism, in all the patriarchal, industrial, pre-industrial, and other forms in which these relations are currently expressed in the uneven world of the global political economy. Tim Pringle’s discussion of Dayton Ohio and the Fuyao Company’s labor practices, established on the wreckage of the General Motors factories, clarifies and elaborates this point. And, as Neferti Tadiar discusses in her contribution, the “hot and cold war” engaged in the Philippines has become a hedge between China and the US, with the Duterte government using its geopolitical and geostrategic position to woo and reject, groom and doom, as arbitrageurs of national wealth, Filipino/a lives as they are bought and sold and circulated in the global marketplace for disposable bodies..

For the discourse of the “new Cold War” to be plausible in this new global material context, China needs to be constructed again as an “other” to a centered, knowable “us”/“West.” Here the “old” Cold War rhetoric of Red China, cunning Orientals, and cleverly embedded communist spies becomes readily available as a discursive default. In this rhetoric, China cannot be understood as an integral part of the functioning of global capitalism, rather, it must be figured, first, as an unfair competitor (cheating to beat “us” at our own game) and then, second, as an adversary and an existential threat. Echoing the old Cold War, China is construed as promoting an unfree alternative to “our” freedoms. And yet, because the Chinese are hugely successful at what they’re doing – and particularly in this pandemic and post-pandemic moment – the threat can no longer be said to be “just” ideological.

On February 19th, President Biden spoke at the Munich Security conference, reassuring European allies that “America is back.” In this proclamation, Biden urgently signaled that the world’s future hung in the balance between “democracy” and “authoritarianism,” with China and Russia (those old Reds) representing the latter. With that framing dichotomy, any action China takes in the world easily can be construed as proof of its imperial ambitions or of the potential spread of its alternative socio-political model. Strangely, this discourse finds an echo in the CCP’s own depiction of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” as truly embodying a socialist alternative to Western capitalism. In their mirror fictions, the CCP cites out-of-context Marxist and Maoist references to substantiate their putative devotion to socialism. More strangely still, the CCP’s “China as socialist alternative” argument has been embraced by sectors of the Western left, anxious to identify their repudiation of US imperialism with an actually existing state.

The renewed persistence in US and in Chinese discourse of largely vacuous references to Maoism, Marxism, and socialism should alert us to how the historical experiences and political practices of an anti-capitalist alternative still haunts the world today. These hauntings identify tensions and contradictions in the global capitalist project, however we might want to call the post-pandemic world (there is good reason to believe it is no longer “neoliberal,” as argued in a forthcoming Chuang collective analysis of the Chinese state). In China, in the last few years, ephemeral and consistently suppressed Marxist student and worker organization have challenged the CCP precisely on its failure to be in any way socialist or even vaguely Maoist. Meanwhile, on the ground in the US, “socialism” is less and less of a political taboo, especially with young people faced with a dismal future of radical insecurity and the rise of a small but potent progressive wing of conventional politics in power. While the hysteria from the right wing about “socialism” abrogating “our” freedoms continues unabated, the realities on the ground are perhaps more optimistic than in recent memory. And yet, imaginative creativity and boldness of action from below will be required for some time to come to begin to transform the crisis-ridden brutality of the one world of global capital we now inhabit into a planetary sustainable system of life for human social interaction.

Rebecca Karl is professor of history at New York University; Fabio Lanza is professor of history and East Asian Studies at the University of Arizona.

— Rebecca Karl & Fabio Lanza, editors