Cynthia Yuan Gao

As Colleen Lye has recently remarked, “much [recent] work on global Maoism studies various sixties movements’ uptakes of Maoism in national isolation, and tends to emphasize the disconnectedness of US Third Worldism from Third World revolutionary realities.”1 This disconnection is a problem not just of academic knowledge but of the material limitations of available archives. Large numbers of documents sit not within university collections but individual apartments and garages, if they have been preserved at all. Compared with Old Left recordings, oral histories of the New Left and its antecedents remain haphazard and sparse. To date the greatest resource on the US New Communist Movement – the anti-revisionist, largely Maoist collection of Left organizations peaking in the 1970s – is the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online (EROL), which has been faithfully stewarded by NCM veteran Paul Saba for years.2 In touring through the comprehensive guide to primary sources from the NCM’s alphabet soup of tendencies, however, one might come away from these writings with the sense that all American Maoists did was write polemics, many of them in strange, stilted language.

A sample article from the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP)’s Revolution newspaper, June 1978.

The printed material, however, was only one part of the story. It would be a mistake to think that the US Maoist wave only read “On Practice” without engaging in any mass work of its own. It’s just simply much harder for us in the present to reconstruct what that practice looked like, hidden as it is now given the secrecy of a milieu conscious of state repression and committed to Leninism, the (often premature) passing away of many NCM cadre, and the epistemic and material shifts which have erased the contributions of Maoisms all over the world from historical memory.

I’d argue though, that it was precisely in practice that Maoism was most influential in the United States, with the wide-scale adaptation of processes like criticism/self-criticism extending far beyond groups like the RCP that described themselves as following the science of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung [Zedong] Thought. Maoist theories were read, adapted, and reinterpreted in the liberation movements – women’s liberation, gay liberation, US Third Worldism – and even beyond formal political groups, from radical psychoanalysts to theater groups. 3 In this context, the designation “practice” indexed not just “mass work” – the Maoist name for what we might call in another context community or grassroots organizing – but an emphasis on the dialectical relationship between learning and doing, individual transformation and collective revolution, and personal and political on the level of subjective embodiment. How then, can we read printed sources with an eye towards understanding Maoism in practice?

One such example embodying these expressions of American Maoism is Ann Tompkins’ 1974 little-studied pamphlet, “Constructive Criticism and Self-Criticism: A Method for Preventing and Solving Problems.” In 1965, Tompkins moved to Beijing to work as an English teacher. She was present for the first several years of the Cultural Revolution in the city of its origin as both participant and observer, arguing for an end to the preferential treatment of foreign teachers and engaging in the struggle against the bureaucracy of her own educational institute. Upon her return to the United States in 1970, she began giving speaking tours and workshops on her experiences as one of the few Americans to have experienced the Cultural Revolution up close. (Unlike Europeans, Americans had a much harder time traveling to the PRC; many did not visit until after the beginnings of rapprochement in the mid-1970s.) The first draft of “Constructive Criticism and Self-Criticism” was prepared for a 12-week workshop for women at the San Francisco Liberation School.

In 2021, I purchased a reprint of this pamphlet from Bolerium Books, finding little other information on Tompkins’ work online.4 (Since then, the pamphlet has been scanned and made publicly available through the Harvard University Library.) “Constructive Criticism and Self-Criticism” is a thick, 100+ page how-to guide to Maoist criticism/self-criticism (C/SC), based upon Tompkins’ years of conducting instructional workshops in the United States, as well as her own experiences with the practice while working on a Chinese collective farm during the Cultural Revolution. The draft I have is the second edition of the pamphlet, with reader feedback from the first edition providing a dialogic experience replicating the polyvocal conversation of an organizational session.

Criticism/Self-Criticism itself was not a Chinese invention. The practice (kritika i samokriitka) was first formalized in the Soviet Union under Stalin in the 1920s, as mechanism through which Party members were critiqued by their peers during collective Party meetings.5 Crucially, the Maoist form (批评和自我批评/piping he ziwo piping) differs from the Soviet form insofar as Mao conceived of C/SC as a practice which was not held behind closed doors for internal Party bureaucrats, but as one in which the masses could participate as well. Moreover, while Soviet C/SC was a fairly formalized process adhering to certain standards of bureaucratic rationality, Maoist C/SC made room for (or even encouraged) the force of subjective emotion in the process of critique.

Prior to Tompkins’ return to the United States, C/SC as a practice had already been taken up by two major outgrowths of the New Left – the women’s movement and the anti-revisionist Left. Second-wave feminists of all persuasions – radical feminists, socialist feminists, and even liberal feminists – adopted C/SC as they built new women’s autonomous collectives. The practice of consciousness raising as developed by Kathie Sarachild and New York Radical Women famously drew from William Hinton’s evocative description of the use of “speaking bitterness” (诉苦/suku) in developing the political subjectivity of women during land reform. Speaking bitterness was a practice in which peasants, particularly women, were encouraged to vocalize the injuries done to them by the landlord class in a collective setting, facing their former oppressors. The US second-wave drew inspiration from this embodied example of narration, confrontation, and political activation, synthesizing it into their vision of a new subjectivity of woman, produced through the personal/political dialectic. C/SC was an important practice in this process. Nonetheless, the adaptation of C/SC across a wide political spectrum of feminists meant that the exercise did not necessarily retain its connection to political and economic revolution. As practiced, C/SC in feminist collectives could be a perfunctory part of a meeting, a ten-minute go around the room that might resemble contemporary meeting check-ins and check-outs.

In the mixed-gender Left, C/SC could also take on more vicious forms. David Gilbert has described the Weather Underground’s C/SC sessions as “horrendous…marred by efforts to pull people down in order to gain a higher rung in the hierarchy.” WUO members were “permeated by the dominant culture of competitive individualism”; the implementation of C/SC in such a context led to drawn-out, emotionally combative sessions.6 And in other organizations, C/SC sometimes became a pretext for physical violence between internal group factions.

Written in a breezy and colloquial style, Tompkins’ “Constructive Criticism and Self-Criticism” begins more like a recipe book or instructions for a board game than a militant polemic. The text starts with a section on how to use the pamphlet, where the author helpfully lays out the materials needed: “a pencil or pen…notebook or paper…[and] company…to discuss it with, share the struggle, and try it out together.”7 Another section centers on questions received through feedback from workshops and previous drafts of the pamphlet, with Tompkins providing annotated quotations from the Little Red Book as answers. Towards the back of the book are “aids to learning” – a bibliography, suggested readings, and definitions of key terms – as well as a “follow-up” section which includes feedback from the first iteration of the pamphlet and a response sheet where readers can write comments to send back to Tompkins for another revision.

Particularly striking is how Tompkins’ formal aesthetic choices reflect her interpretation of Maoism and the dialectical process of criticism/self-criticism. In translating the importance of practice, Tompkins retains the folksy, earthy language of Mao’s aphorisms not through direct translation but the creative repurposing of American idioms and mass culture.8 Tompkins’ approach is thus a far cry stylistically from the output of many self-identified Marxist-Leninist-Maoist organizations of the time, whose prose style tended to mimic the stilted language of Peking Foreign Language Press translations.9

After the introductory “how-to” section, Tompkins begins her discussion of C/SC with stories of her personal experiences on the Evergreen Commune in Beijing. Two of these reflections are sectioned with the delightful titles: “Why Should We Admit Our Mistakes? (Tomatoes)” and “Putting the Interests of the People Before Appearances (Cucumbers).” The first part of these titles are quotations from the Little Red Book. But by adding tomatoes and cucumbers to the recipe, Tompkins not only literally grounds these quotations in a more practical soil, but also contextualizes C/SC as a practice of the Chinese rural everyday through which ordinary people – farmers and intellectuals alike – learn how to become political actors and grasp philosophical concepts in the shared process of agrarian production.

In “Tomatoes,” a farm leader chastises a young woman for not being more careful in pruning tomato vines. When the youth becomes defensive, an older woman from another row sings out, “Anyone, no matter who, may criticize us, because we serve the people.”10 The conflict passes without further comment. In analyzing this story, Tompkins suggests that the invocation of the quotation was not an example of a brainwashed peasant woman speaking from rote memorization. Rather, the quotation functioned as a reminder to the defensive youth that criticism was not meant to injure or harm her selfhood, but to improve the farm’s yield for the greater collective good. “It’s a funny thing how important it is to realize that if you just stop doing a mistake, it goes away,” Tompkins concludes. “You’re not guilty of that problem anymore, after you correct it.”11

In “Cucumbers,” a group of high school youth come to the commune to contribute to production. Eager to prove themselves in their re-education, the youth rush to keep up with the other workers in hoeing cucumber vines. In their inexperience, however, the students cut down a quantity of unripened fruit, resulting in a great waste of harvest. A communal meeting takes place right on the fields, with the angry peasants leading an immediate criticism session in the fields. The students are chastised for their haste, which Tompkins translates for the American reader as a kind of “keeping up with the Wangs.” This attitude, Tompkins tells us:

“comes from capitalist society…[it] is not in the interest of the people because it is trying to put something forward which is not there. If you don’t have experience, don’t try to cover it up. Learn! Take your time: learn. But keep the interests of the commune and the whole people in mind.”12

Here is an oblique lesson for the US New Left, comprised as it was primarily of young students eager to prove their revolutionary mettle. The rapidity with which new ideas like Maoist C/SC were internalized and put into practice could lead to the kinds of power plays that Gilbert and other Weathermen later described. In this time period, the emotional and physical demands of being seen as properly revolutionary pushed a great number of participants out of the social movements. Using Tompkins’ analogy, perhaps we could think of them as casualties of a premature harvest. And yet, though the cucumber story uses student fervor to make a broader critique, it does not dismiss the righteousness of the students’ fervor in the first place. Encoded within Tompkins’ pamphlet then, is perhaps an internal critique of US Maoism’s militancy in practice which does not dismiss the righteousness of its beliefs in theory.

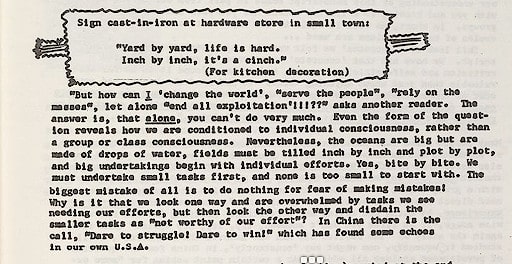

Inch by Inch, It’s a Cinch!

Tompkins’ pamphlet also serves as a reading guide to the Quotations of Chairman Mao. Many sections of the pamphlet end with quotations that readers may find useful, along with discussion questions to promote understanding. Tompkins also supplements these quotations with her own insertions of local idioms and folk wisdoms that contextualize Mao’s exhortations within a more familiar style for the American reader. For example, Tompkins reproduces this quotation, part of a 1957 speech titled “All Reactionaries are Paper Tigers” (一切反动派都是纸老虎/yiqie fandongpai dou shi zhilaohu), to provide encouragement to readers just beginning the process:

“…Strategically we take the eating of a meal lightly…we know we can finish it. But actually we eat it mouthful by mouthful. It is impossible to swallow an entire banquet in one gulp…”13

Later on in the pamphlet, Tompkins discusses the contradiction between the personal and the political that C/SC embodies – how it simultaneously indexes the intimate relationship between both poles (and the potential of the dissolution of the two as discrete entities) as well as the vast gulf between transformation in one pole inherently leading to another. Sandwiched between dense paragraphs is this graphic, creative repurposing of an American banal platitude.

On its own, perhaps the aphorism necessarily doesn’t mean much – indeed, Tompkins isn’t suggesting that the original has any communist content. But in the context of Tompkins’ stories about the painstaking work of developing mass consciousness through labor and study with others, the phrase begins to take on the quality of a mass campaign slogan. Furthermore, her repurposing of an American idiom strikes me as a particularly Maoist move – the adaptation of existing folkways into a socialist program was not only a hallmark of the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts, but the move is itself a dialectical operation. In repurposing a familiar, existing grammar to serve a new language, Tompkins demonstrates a practice through which Maoism becomes not an immediate deus ex machina to deliver one from capitalism, but a mechanism through which one struggles with and through the contradictions inherent in one’s own world over the longer arc of history.

Don’t Wave It, Use It!

Indeed, Tompkins herself emphasizes that C/SC, and by extension Maoism as a whole, can only be grasped through practice. In a section titled, “Don’t Wave It, Use It!”, Tompkins critiques Cultural Revolution practices like waving the Little Red Book and badge collecting as “form devoid of worthwhile content.” While maintaining the importance of defending the Cultural Revolution from American charges of the “cult of the individual” or even “Hitler Youth,” Tompkins nonetheless argues that these practices were “devoid of true revolutionary content.” Granted, this critique is limited – Tompkins places the blame upon Lin Biao, by that point purged and a safe target – but at the same time Tompkins offers a very important intervention into the American Maoist scene:

“The Quotations are a good beginning point, and were that for many young people in China, and can still serve that way for many of us in the United States who are still not familiar with such fundamentals. It is not a ‘bible’ but a useful tool. It has no ‘answers’ to specifics, but suggestions for method.”14

Beyond the counterrevolutionary machinations of Lin Biao, however, what would push people – in the PRC and the US – to wave the Little Red Book instead of using it? One of the central tensions within Tompkins’ pamphlet is the place of subjective feeling and emotion in the process of criticism/self-criticism and thus, her theory of revolutionary transformation as a whole.

Tompkins describes an early Cultural Revolution event where workers and students at her institute came together to critique the school’s administrators. The school’s masses consign the bureaucrats to menial work – ‘sweeping streets and cleaning toilets.’ On some particularly enraging targets, the crowd places dunce caps and signs that read phrases like ‘I am a bourgeois academic authority.” In a section titled “Caps and Signs; Vengeance,” she explains that the fervor with which the struggle began prompted later self-reflection.

“It was only a few weeks before we…began to discuss our actions and attitudes: ‘What is the meaning of putting dunce caps and signs on people?’ For those of you who chuckle at that, think twice. I trapped you. Because you, as we, enjoyed our/your vengeance.”15

This passage is used to explain a turning point in the struggle against the administrators, explaining that behind many spectacular instances of caps and signs followed weeks and months of reflection and rectification, producing a higher unity. Crucially, however, Tompkins does not deny the propulsive force of emotions in the process of criticism and struggle. One must account for subjective emotion in attempting to achieve a greater closeness to objective reality. Bound up in the process of struggle are powerful emotions which compel us to extract vengeance and to laugh at the misfortune and passions of others. In this, Tompkins insists, all are implicated, not just the Chinese zealot but the American chuckling from a distance. Though the context of Cultural Revolution China and 1970s Bay Area are quite different, the dialectical relationship between subjective emotion and human action, and the necessity for ruthless critique of both applies to all. Elsewhere, Tompkins tells her readers to pay close attention to the subjective responses each Mao quotation produces in themselves. Like a psychoanalyst, she seems to ask her readers to stop and pay attention, asking: and how does that make you feel?

What I believe distinguishes Tompkins’ approach from a devolution into group therapy (a therapeutic form which Maoism undoubtedly did influence in some way) is her insistence that the development of consciousness in the individual must always be part of a larger struggle towards some kind of group unity. This collective unity, though composed and produced through the subjective relations of group individuals, is what provides the basis for the capacious social vision of cultural revolution. At the same time, by grounding C/SC in practice itself, Tompkins centralizes the stubborn place of subjective and individual emotion in what is supposed to be a scientific process leading to more rational decision-making.

These dialectical tensions between subjective and objective, individual and collective, and emotion and rationality were at the heart of the US New Left’s political preoccupations. In this context, the ideas and practices of the Cultural Revolution were particularly attractive. For some, the turn towards Maoism represented everything that was “wrong” with the “bad Sixties.” I read US Maoism instead as an expression and extension of the US Left’s fundamental contradictions – the great expansiveness of its anti-imperialist and anti-authoritarian vision that existed alongside its often severe sectarian narrowness. Everything was subject to criticism, and yet new forms of criticism were marshalled to ward off others. In this, the line between subjective and objective and the relation of each to legitimate critique became blurred.

Many NCM groups, for example, were deeply hostile to women’s liberation while also viewing homosexuality as a degenerate, bourgeois deviation, even during the devastating years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. They were unable to resolve this contradiction in themselves – spurred to politics by the promise of cultural revolution, yet incapable of accepting the extensions of that revolution into their own political culture. Maoism sanctioned the driving force of emotion in politics, and yet, when presented with the actuality of experimentation with love and desire, many NCM groups attempted to close down such a challenge through a retreat into polemical rigidity.

Tompkins’ pamphlet does not resolve this problem, but she does represent a more heterodox approach which foregrounds the contradiction. One reader writes in, questioning Tompkins’ assertion that C/SC can be useful in all facets of life, even in subjective situations that are not explicitly political. “Thanks for the very honest exposition of your point of view, Tammy, and for sharing your feelings so fully and vividly!” Tompkins begins, before defending her point.

“I think that you will find that ‘a dinner party’ is ‘political practice’! True, it is not a revolution, but in a bite size way, it is a part of, or a form of, ‘political practice’.

Now we are emphasizing that personal is political, and political is also personal. And yet, they are also not synonomous [sic] usually. But, for me, the goal has become to have them either be synonomous [sic], or to have the political dominant and the personal where it diverges from the ‘serve the people-type politics’ should be subordinated!”16

“Dinner party” and “revolution” are terms which could stand in for two caricatures of the major types of Maoist-influenced movement politics in this era – the consciousness-raising circles of the autonomous women’s movement and the guerrilla militancy of the Leninist Left. These caricatures map onto as well the tension between subjective and objective – between female subjectivity and material class contradiction as the starting point of one’s politics. To be sure, these two poles were in reality not always in such stark conflict, and both had more in common than each camp might have admitted at the time. But in Tompkins’ vision of a shared horizon in which “personal is political, and political is also personal,” she brings forth both the possibility of a synthesis between these two poles, through a revision of the meaning of the personal itself. If under bourgeois society the personal is synonymous with the individual, Tompkins calls for a redefinition of the personal in terms of one’s relation to the collective. This does not, however, mean that the subjective disappears. Indeed, following the spirit of the Cultural Revolution, the subjective is in fact always operative: it is the place from which one begins to apprehend the collective motion of history.

I Open Myself to Love, I Open Myself to Despair

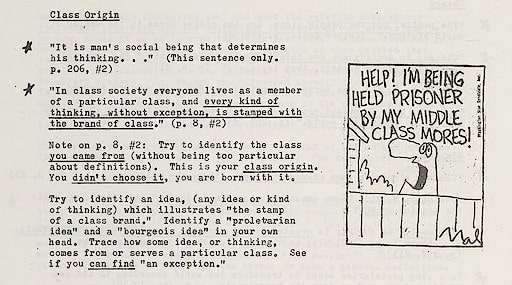

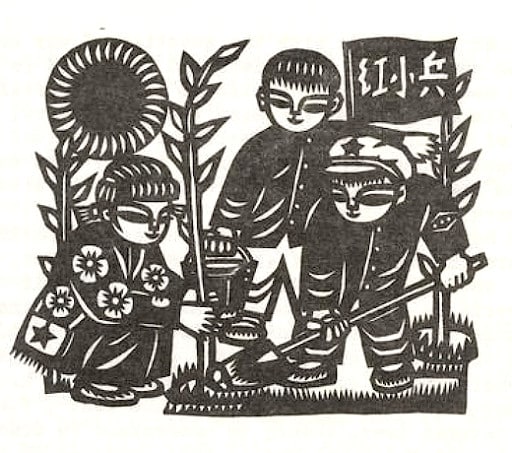

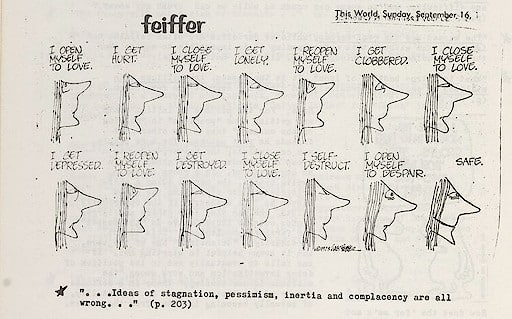

Peppered throughout “Constructive Criticism and Self-Criticism” are small images and comics that provide levity and instruction. This newspaper comic panel, taken from The Washington Star, runs alongside an exercise on class ideology based upon quotations from the Little Red Book. Included as well are examples of Chinese folk art like papercuts and woodblock prints that played an instrumental role in the aesthetic vocabulary and educational practice of the Mao era.

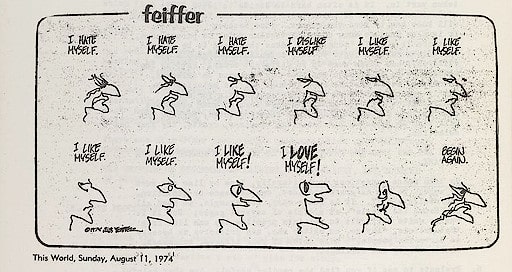

In making use of both graphic forms, Tompkins’ pamphlet again translates a Maoist method not in literal form, but in essence. The art of paper cutting was not a folk genre instrumentalized by New Left artists, but comics certainly were. Cartoons were a central part of the American countercultural aesthetic, and provided a similar educational function in political pamphlets, bringing a synthesis of political ideas and aesthetic pleasure to wider audiences.17 For the New Left, cartoons and illustrations were a cheap, easy way to add visual interest to printed materials in an era before the accessibility of mass consumer photography.

Synthesized in the above Feiffer comic is Tompkins’ articulation of C/SC – and by extension, dialectical materialism – as an embodied process felt at the subjective level. Though the comic focuses on an individual “I,” perhaps we can characterize the New Left as a collective journey through these emotions: an “opening to love” in a mass, global sense. The era’s “eros effect” – as George Katsiaficas, drawing from Herbert Marcuse, has articulated – produced a concept of revolution which stretched far beyond formal political revolution and economics, permeating down to the cellular level of one’s everyday habits of mind and consciousness. In short, cultural revolution.

But in opening oneself to love, one also opens oneself to the real possibility of its failure or rejection – to be “clobbered,” to be “destroyed,” to have one’s emotions cycle up and down like a Kondratieff wave. And this is in fact what happened in the 20th century – not just in terms of the complicated aftermath of many of the experimental forms of the sexual revolution, but in the failure of anti-colonial nationalisms and communist movements to live up to the radical dreams which so many loved so deeply. (Indeed, Tompkins herself would come to express her disapproval of “reform and opening” China, commenting often that “the US hates China because it does capitalism better.”) In reading “Constructive Criticism and Self-Criticism” from the other side of the end of history, one could say we are reading from the perspective of the stagnation which followed this global opening to despair. And from this vantage point of despair we are far more likely, as Lye has suggested, to be skeptical of “the emancipatory promise of a politics of subjectivity.”18

It may be tempting in such times to search for what is truly “material” and “objective,” to seek higher ground from the muddy swamp of emotion. But I would argue that the power of the Maoist approach to C/SC is its acknowledgment that Marxism in practice is not only foundationally inseparable from the unwieldy subjective, but where such practice in fact begins. This crucial insight was the spark for a global generation of radical dreams and nightmares; it is the fundamental precondition for our own contemporary subjective despair. Our challenge then, is to understand our present emotional position of suspicion and stagnation as a contradiction through which one begins the dialogic cycle anew, rather than as a teleological expression of the failure of a Marxist politics of subjectivity. I hate myself! I love myself! Begin again.

Works Cited

Buhle, Paul. Comics in Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Borderland Books, 2009.

Carol, Estelle. “The Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective: A Memoir.” Feminist Studies 44, no. 1 (2018): 104-124.

Getty, J. Arch. “Samokritika Rituals in the Stalinist Central Committee, 1933-38.” The Russian Review 58, no. 1 (1999): 49-70.

Gilbert, David. Love and Struggle: My Life in SDS, the Weather Underground, and Beyond. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2011.

Katsiaficas, George. The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968.” Boston, MA: South End Press, 1987.

Lewis, Victoria. “From Mao to the Feeling Circle: The Limits and Endurance of Collective Creation.” In A History of Collective Creation, edited by Kathryn Mederos Syssoyeva and Scott Proudfit. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Lye, Colleen. “Identity Politics, Criticism, and Self-Criticism.” South Atlantic Quarterly 119, no. 4 (2020): 701-714.

Mao Zedong. “All Reactionaries are Paper Tigers.” Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Vol. 5. Peking Foreign Language Press, 1975.

Cynthia Yuan Gao is a PhD Candidate in American Studies at New York University and incoming Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies at Middlebury College. Her current project examines the influence of Asian revolutionary thought and practice on U.S. social movements from the 1960s onward, with an emphasis on Left theorizations of identity politics.