Ruodi Duan

For a generation of Black nationalists in the United States, Maoism aligned with their commitments to racial nationalism, socialism, anti-imperialism, and cultural revitalization. But beyond theory, perceptions of China’s support for minority equality and self-determination within its borders further enhanced African American affinities with Maoism. In other words, enduring relations between African American radicalism and socialist China in the 1960s and early 1970s hinged on an equivalency of racial and ethnic identities—one underpinned by conscientious efforts of the Chinese state to promote the exceptionalism of its minority policies, as well as the centrality of land and power to twentieth-century Black nationalist politics.

As early as 1953, African American labor activist Louis Wheaton, who visited China for the Asia-Pacific Peace Conference a few months prior, noted that in the northeastern industrial heartland of the country, ethnic minorities found employment in a diversity of professions. For Wheaton, this presented a stark contrast to cities in the United States, where African Americans and other minorities were restricted to the most undesirable occupations. Wheaton singled out the Oroqen in the provinces of Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang as an example of a minority nationality that had realized political and economic self-determination in their autonomously governed areas, while the state provided much-needed vaccinations and primary education for youth.1

When Robert F. Williams, a civil rights activist from North Carolina and among the earliest advocates of armed self-defense, travelled to China in 1964, he requested to tour minority homelands. He and his wife Mabel, along with their two teenage sons, traversed Inner Mongolia and Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, where they met with ethnic Korean students and peasant families. They marveled at Yanbian University, one of the first institutions in the country to offer a research program in minority studies. Further signaling empathy for African American struggles with regards to the equality and cultural self-determination granted to its minorities in Yanbian, municipal officials displayed banners proclaiming support for African American civil rights in Chinese and Korean scripts.

In Beijing, the Williams family visited the Cultural Palace of Nationalities in Beijing and the Niujie Mosque where Hui Muslims gathered in peaceful prayer—for Williams, a radical departure from the persecution that the Nation of Islam encountered back home. He chose to include the lecture “Minorities’ Policy in China” in his late 1970s speaking tour in the United States sponsored by the U.S.-China People’s Friendship Association, as did Vicki Garvin, a Black educator and union organizer from New York City who lived and worked in China from 1964 to 1970.

The sense of Chinese ethnic equality did not only impress Marxists like Vicki Garvin or those long committed to the liberatory potential of China like Robert Williams. When Ron Karenga, a Black cultural nationalist best known for establishing the Pan-African holiday of Kwanzaa, embarked on a summer 1977 tour of China with twenty other Black educators, he noted the non-discriminatory treatment accorded to national minorities. At the Central University for Nationalities in Beijing, he lectured Chinese faculty and students about independent Black education in the United States and its importance for African American liberation. Karenga’s US Organization had engaged in violent clashes with the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles in 1969, spurred on by political disagreements about the centrality of culture or class to Black liberation and the counterintelligence operations of the FBI. But he and Huey Newton, the Black Panthers’ Minister of Defense, shared an admiration for Chinese models of minority governance.

It was not a one-way street. Chinese intellectuals and officials often ruminated on African American oppression and resistance as part of their own efforts to understand China’s evolving policies regarding its minority nationalities. The mechanisms and histories of Black exploitation in the United States allowed them to sharpen analyses about the relationship between the “race question” 种族问题, the “ethnic question” 民族问题, and capitalism—a relationship applicable to the multiethnic Chinese state, which included territories still undergoing socialist construction. The bilateral nature of this exchange challenges a fundamental assumption that often underlies studies of “Global Maoism,” namely that Maoism, as theory or set of revolutionary practices, unidirectionally flowed outward from China to the world. Yet, as the interrelatedness of racial and ethnic discourses in 1960s China shows, Maoism as articulated within China itself was shaped by external conditions—in this case, by the course of African American political struggle and developments in the U.S. civil rights movement.

Modern equivalencies between global Blackness and Chinese minority identities date back to the early twentieth century. Popular culture in Republican-era Shanghai once compared the peoples and cultures in China’s vast frontier regions, such as Taiwan, to communities in Africa and the South Pacific perceived as similarly “primitive,” employing racial imagery and descriptors of “Africans,” “blackness,” and “savages” for both. On the Chinese “national question” of the 1950s, Jeremy Tai concludes that this impulse to differentiate race 种族 and nation or ethnicity 民族 arose in part from the necessity of distinguishing “race” in capitalist contexts from “ethnicity” in socialist ones. In other words, Cold War exigencies unmoored Chinese analyses of racial capitalism from internal debates about ethnic politics. Consequently, the accompanying logic that racism presented a problem only in other societies but not in China persists to the present day. While Mao-era officials indeed considered questions of race and ethnicity as qualitatively different, their relationship to each other—inflected by ongoing U.S. civil rights struggles—was more elaborate and entwined.

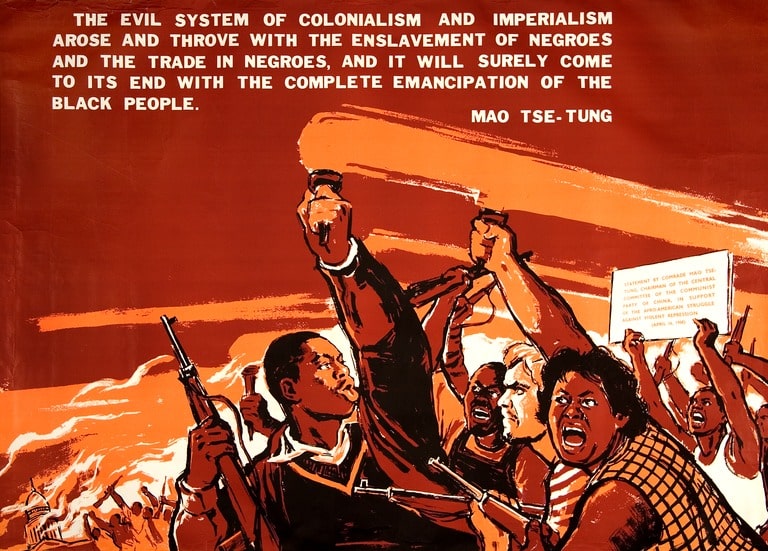

After Mao Zedong first declared his support for the African American struggle in August 1963, Chinese intellectuals explained that in the United States, a perverse logic prioritized race over nationality and ethnicity. White supremacists consciously blurred the lines between race and ethnicity to justify segregation and class exploitation, creating the illusion that any difference between Black and White was attributable to biological and not socio-political reasons. As such, African Americans constituted not a “race” but a nationality, with “racism” a capitalist hoax to suppress the resistance and political consciousness of all oppressed nationalities. Accordingly, he surmised, as national liberation movements arose everywhere, the “theory” of race would meet its end.2

A central tension was embedded within these treatises and the Chinese reception of the Williams family: for example, there was an uneasy collapse of African American national liberation and the liberation of China’s national minorities. Official exhibits and itineraries designed for Robert Williams suggested that the model for African American liberation might be the status of minorities under the “already-liberated” post-1949 Chinese nation-state. The former construction held African Americans as progressing towards national liberation, but the latter hinted at possibilities for the political and cultural autonomy of minority populations granted under Maoism within the national state. Was this a contradiction of sorts? Did Chinese representatives see African Americans as progressing towards national liberation itself or as representing respect and equality within a soon-to-be liberated nation-state?

Liu Chun 刘春, a theoretician of and administrator in ethnic affairs from the 1930s into the 1980s, took on this precarious equivalence when he explained that the African American experience actually demonstrated key characteristics to questions of national oppression, as the primary contradiction is never between all members of one nationality and all members of another. Rather, it is a matter of the ruling class within the oppressor nation exploiting the majority of the oppressed nation, from industrial workers and laborers to the peasantry. In the United States, the reactionary ruling class of the white race did not represent the interest of every white person—a distillation which reflected ethnic dynamics within China, where full socialist liberation and the resolution of historically inherited contradictions remain incomplete. However, Liu wrote, the national bourgeoisie within oppressed nations often do join the broad masses of working people in the country to oppose structures of imperialism. As such, the proletariat should unite with them to confront imperialist oppression. At the same time, a small number of reactionaries within these oppressed nations can and do unite with the imperialists to preserve a political or economic system which benefits them. In this way, Liu wrote, African American political movements embodied the true meaning of Mao’s statement that “the essence of national oppression is class oppression.”3

These connections between race and ethnicity in post-1949 China indicate the importance of appreciating “Global Maoism” as a phenomenon that remade ideas about nationalism and liberation in China and the world. This dynamic expressed itself in diverse, varied ways. In November 1965, the folk arts division of Yunnan’s National Defense Song and Dance Troupe toured West Africa, delivering performances while learning African numbers to perform in Beijing, signaling provocative links between Yunnan and West Africa. In addition, Thomas Burnham hints at the figure of Zhang Shungao, of the Tujia minority in Yunnan and a tea specialist who received Cold War assignments in West Africa to develop local expertise in tea planting and cultivation. Among his deployments was a term in Mali from 1967 to 1974 followed by the Republic of Upper Volta, or present-day Burkina Faso, from 1977 to 1980. Beyond African American nationalists of the 1960s, other representatives of global minority groups saw in China a model and supporter of indigenous liberation. Maori delegates to China in 1973 toured ethnic homelands with a keen eye to minority self-governance and cultural self-determination under Maoism, which they contrasted with the marginalization of Maori and Polynesian communities in New Zealand.

In sum, these largely forgotten episodes of cultural and ideological solidarity stand as a reminder that to understand “Global Maoism” calls for seeing not only how those abroad received and retooled the theoretical contributions of Maoism, but also the ways in which ideas about race, ethnicity, and nation were transformed within China itself in the course of such exchanges.

Ruodi Duan is Assistant Professor of History and East Asian Languages & Cultures at Haverford College. Her research and teaching interests include modern Chinese social and political history, comparative ethnic studies, China-Africa relations, and international histories of the Cold War.