Carey Park

I situate propaganda paintings in a system of “intuitive agitation.” Called “visual agitation” (직관선동 直觀煽動) in North Korea, the Sino-Korean roots of the concept literally mean “to agitate by seeing with one’s own eyes.” This is precisely what happens when propaganda paintings are installed in everyday locations of people’s lives, in rice fields and in villages, at construction sites and places of work. There are various forms of visual propaganda paintings such as slogans, breaking news, competition charts, and honor boards. Slogans reflect the political agenda at the national level, while news stories deliver the latest local developments. Propagandists responsible for generating visual propaganda are dispatched to workplaces, who upon observing noteworthy acts quickly sketch a painting or write a news story to post on the notice boards. Competition charts display collective goals, and may include individual contributions toward them, thereby inciting competition between work teams and between individual workers. Honor boards are additionally used to publicize the most exemplary teams and individuals.

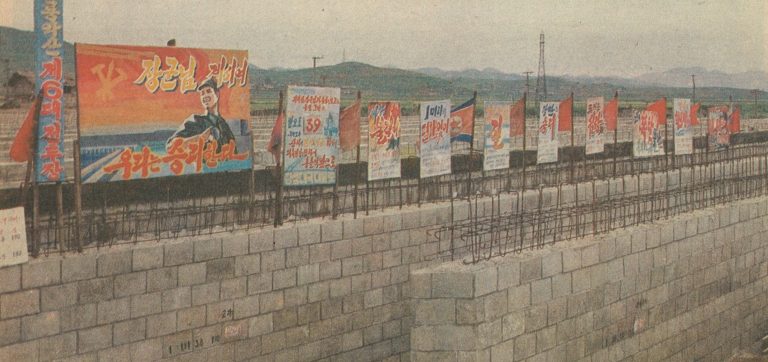

Examples of visual agitation at a construction sites (All images come from the original article)

Protagonists of Propaganda

North Korean discourse claims that visual propaganda enables the masses to feel empowered to fulfill collective plans and accomplish national and party goals. Those outside this system thereby assume that the constant observation required in the creation of visual propaganda constitute surveillance, imposing indoctrination on the recipients of propaganda. But can this form of agitation at the local level actually increase individual productivity and fulfillment? Articles in the party newspaper Rodong Sinmun quote dispatched propagandists who say that they wanted to paint more people but ran out of paint, or that they received many requests to have additional workers featured in their news stories.

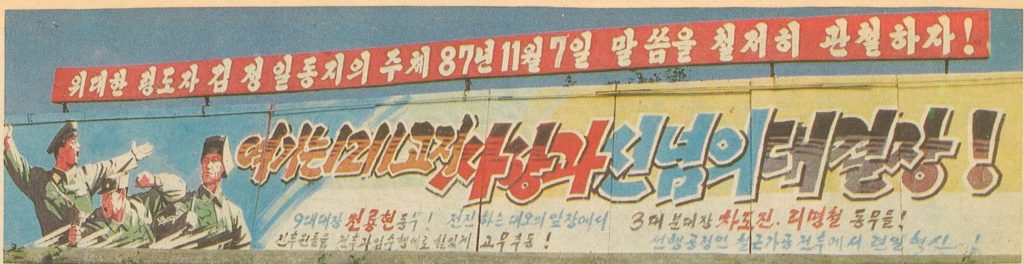

Visual agitation featuring names of local team leaders

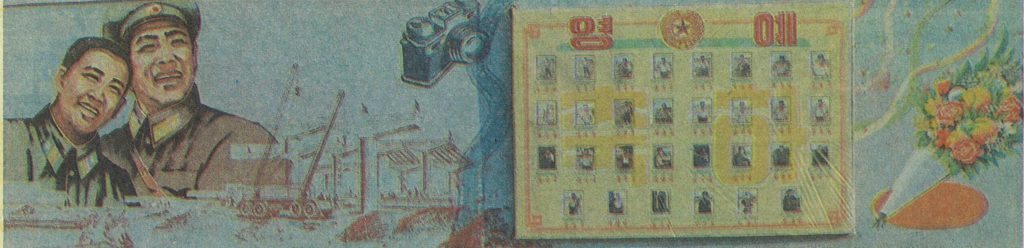

Example of “Socialist competition chart”

Example of honor board featuring individual workers

All these, of course, are ways to increase productivity, but how are workers motivated to increase productivity in capitalist societies by contrast? Workers are evaluated and differentiated according to higher or lower wages to maximize productivity through monetary incentives and controls. How is it possible then, that in North Korea, propagandists can motivate workers to increase productivity simply through paintings? The answer is not directly apparent, but when asked about this, a North Korean defector responded that such devotion is at the foundation of North Korean society. If someone is selected for outstanding work in a collectivist society, not only the individual, but the whole group in which the individual is part, shares in the honor. The defector explained that this link between the individual and the group was the most important characteristic of North Korean society. Because the propaganda paintings change every week, they are comparable to televised dramas, for which people excitedly wait in anticipation for the next installment to see who was selected. This phenomenon was stronger in tight-knit rural communities with limited access to other forms of mass media found in urban centers.

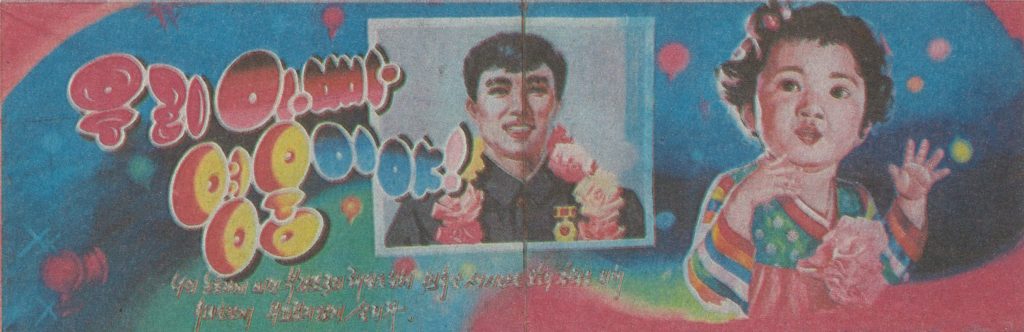

“My father is a hero!”

“Big brother! Come back a hero” with specific names of transportation workers painted in red

The majority of officials dispatched to draw propaganda paintings are not trained graduates of art universities, but rather practice art as a hobby with a level of talent. Although propagandists in the cities may be university-educated, the dispatched painters in the countryside and in small villages usually have no formal training. Because of this difference between urban and rural areas, a visit by a famous artist from the Mansudae Art Studio, for example, to regional areas for visual agitation would have an enormous impact.

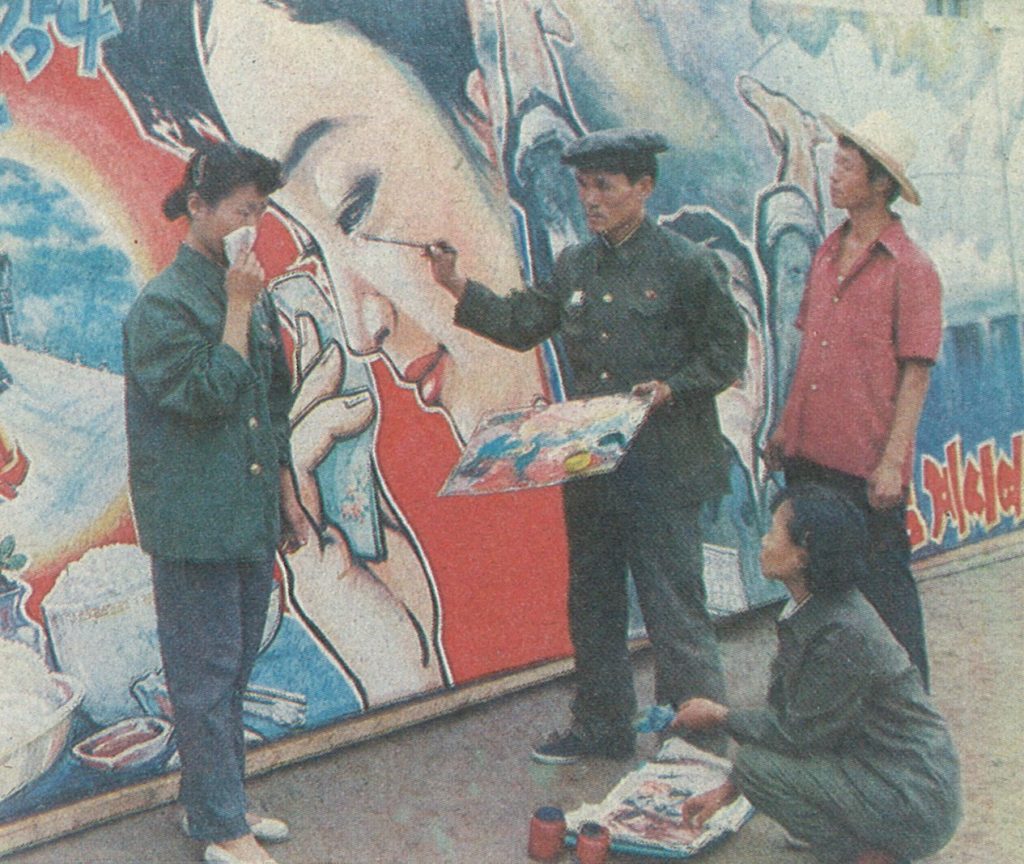

As a defector explained, the sight of a famed artist with sketch book in hand is comparable to South Korean reactions upon seeing a celebrity. In this context, a visit by a professional artist is not perceived as surveillance, but rather, incites villagers to work harder for the chance to be featured in artistic works. Alongside these propaganda paintings created on-site, there are also works that simply copy samples distributed from the capital as important tools to convey national policy. Such propaganda paintings must conform to set standards and there are collective discussions about their content during the creative process. Once such paintings are completed, they are photographed or collected in a pictorial book to be distributed across the country. Local propaganda officials then copy those paintings to distribute them throughout their assigned areas. In this way, the paintings are able to convey national policies to every corner of the country.

“All people aid the rail transport!” (1969)

Despite the importance of such centrally coordinated visual agitation, it is not the professionally produced propaganda paintings distributed nationally, but the locally produced visual agitation created by local propagandists without formal arts training that is at the heart of internalizing visual agitation. This is because they directly depict the real life stories of the local people in their daily lives, how they work, exercise, eat, rest, and enjoy their free time.

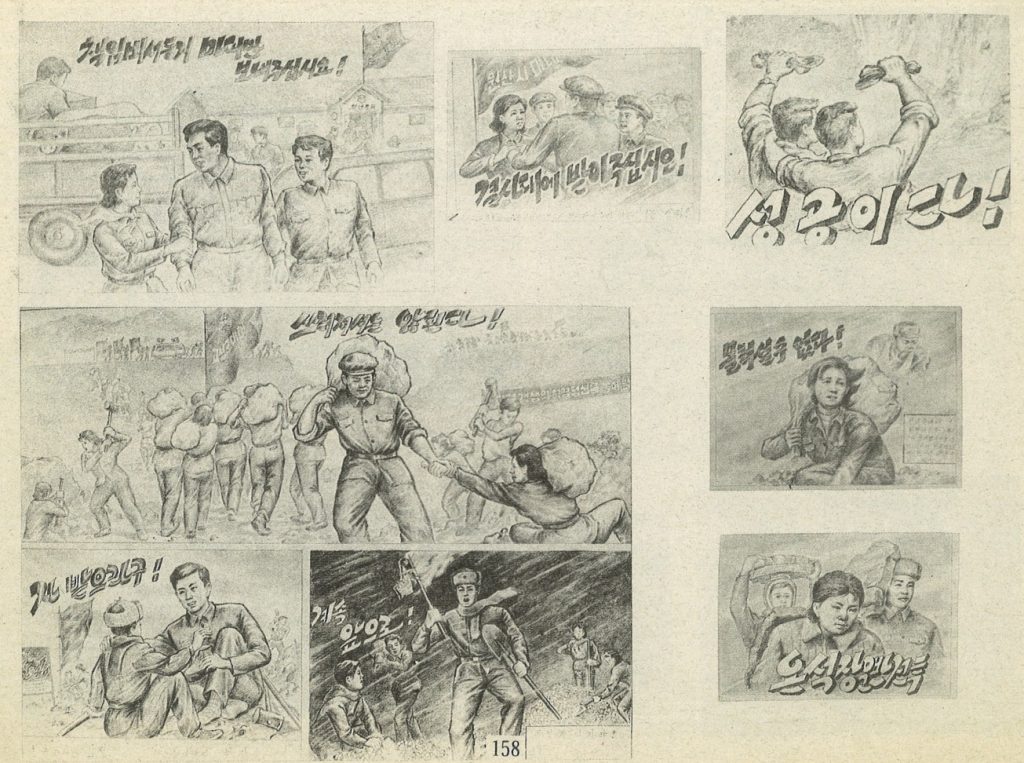

Examples of sketches by propagandists

Creators of Propaganda

Visual propagandists are officially called “visual agitation officials” (직관원) in North Korea. As mentioned above, the vast majority have no university education, but many with talent in the arts hope to become a visual propagandist. To be selected for such a position is a proud achievement, especially for those in the North Korean countryside. Those striving for higher education also covet the job in the hopes of being nominated to attend an arts university. Since agitation propaganda is an important way to convey national policies, propagandists must work closely with party officials, which becomes an important networking opportunity to forge political connections. Professionally trained artists may also choose to be dispatched as propagandists as this can be an important criteria for party membership. In these ways, the system functions by inciting voluntary participation in the creative process, while elevating productivity.

Propagandists at work

For example, the magazine <Korean Art> (조선예술) featured an article on the celebration of the seventieth anniversary of the Korean Workers Party involving a thousand performers. Such large-scale cultural and artistic events as the Arirang Festival are a common sight in North Korea. According to a defector, her hometown had also organized a choir performance with some 500 people on stage, while only 100 people were left in the audience. The majority of the villagers were not passive consumers of the show as members of the audience, but participated actively as creators, much like the local propagandists themselves.

North Korean citizens are not made to internalize propaganda by simply consuming it. Rather, it is through their direct participation that the content is internalized. This system of agitation propaganda through the arts is, what I call, the politics of relational aesthetics. Propagandists are sent to every rice field, every construction site and workplace to engage in intuitive agitation, and they are recruited from the population at large without any prior advanced education in the arts. The direct involvement of so many people—500 on stage compared to 100 in the audience—is the singular characteristic of North Korea’s system of agitation propaganda.

As noted at the outset, visual agitation means to directly see and experience the objects of agitation propaganda. Rather than a unilateral process of consumption, it is the North Korean people as both protagonists and creators of propaganda that make North Korean agitprop so effective, undergirding the country’s stability despite its many continuing challenges.

Carey Park is Professor of Arts and Culture at the National Institute for Unification Education in Seoul, Korea. Her major publications in Korean include Modernity and Tradition: Era of Chaos, Creative Identity of Artists (2014), “Modification in Icons and Forms in North Korean Art Policy” in Art in North Korea: Its Past and Present (2016), and “Paekdu Mountain: The Invention of Tradition and Its Emblems,” Korean Bulletin of Art History (2011), among many others.