Hee Sun Choi

After the division of Korea in 1945, the study of North Korea in the South proceeded under imperfect conditions, in which not only the flow of people and material goods but also information and academic exchanges were prohibited. South Korean researchers had to be careful about staying within the legal boundaries of the National Security Law when accessing information classified as “specially restricted materials” at home and abroad.

Research into North Korean design and material culture faces the same challenges. Since it is difficult to visit in person, observe objects, interview users, or conduct statistical surveys, researchers need to rely on limited, practically banned sources for a considerable part of their research. Moreover, the problem of copyright on North Korean visual materials poses an even greater barrier during the publishing process.

My two-volume study Industrial Art as Design in North Korea was published in 2020 despite such underlying methodological disadvantages that come from the fraught nature of inter-Korean relations. The volumes together trace seventy years of North Korean industrial art from 1945 to 2018, covering the role of industrial artists as designers of national symbols after liberation from Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) to their expanding roles after the Korean War (1950-1953). The study also provides analyses of North Korea’s national exhibitions and key designs after the division of Korea up until 2018.

Cover of Industrial Art as Design in North Korea (2020). The two-volume work considers North Korean industrial art in the design of posters, logos, typography, household items, machinery, apparel, architecture, public facilities, and other everyday objects.

I began this research by collecting photographs of original sources on art, economy, culture, and tourism as well as propaganda materials for domestic and international audiences. I also compiled quantitative data on some three thousand items, including the years of production or release and identifying the designers with their university or studio affiliation, thematic focus, representative styles, and awards received at national exhibitions. I based the information on documentary research of sources such as History of Korean Art (1990). The examples in the sources varied from electronic products and furniture design to apparel and textile design to graphics and typography. Among them is the machinery blueprint for the Chollima tractor (named after a mythical winged-horse that was also the name of the North Korean production campaign similar to China’s Great Leap Forward), in which North Korea has taken much pride.

The two volumes contain a selection of over one thousand works representative of North Korean design, organized chronologically by year. Rather than introducing the designs merely in the form of a photobook, I offer an overview of the significance of design in North Korean society, including previous scholarship and relevant sources, so that readers understand the characteristics of North Korean industrial art for the different time periods of the past seventy years.

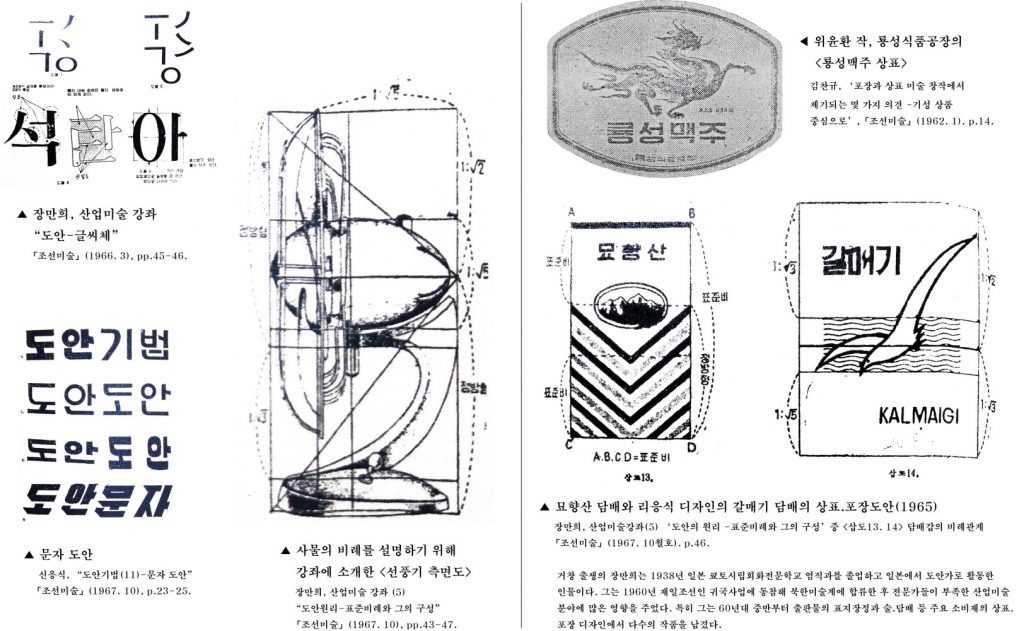

Mid to late 1960s North Korean examples of typography, industrial design, brand logos, and product packaging. From Industrial Art as Design in North Korea: Vol. 1. 1945-1999 (2020): 233, 287.

However, I do not presume to claim that my work covers a comprehensive history of North Korean design. As explained above, there were limits to the scope and quantity of visual sources I could collect from South Korea, and considering the nature of the North Korean state, it is necessary to verify the accuracy of the primary sources collected. Additionally, it was no easy feat for me, as a South Korean national, to throw out preconceptions about the North and maintain an objective attitude during the research process.

Design historians in South Korea generally adopt methodologies used in anthropology or ethnography for material culture research, including documentary surveys, observation of objects, oral interviews, among other methods. However, due to the lack of access and security concerning sources, North Korean industrial art studies in the South often rely heavily on documentary research of almanacs, art books, specialized magazines, and other secondary sources.

Studies of North Korean art in the South began in earnest only after the July 7, 1988 Special Declaration for National Self-Esteem, Unification, and Prosperity. As part of the Declaration, the South Korean government began to release previously banned North Korean sources to the public. In 1989, the Korea Culture and Arts Education Service (under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and Information) began researching arts and culture in North Korea in what became the first step in North Korean art studies. As the relationship between the two Koreas improved toward the turn of the 21st century, North Korean artworks found their way to exhibitions in the South and little by little, books about North Korean art began to appear. Yi Ku Yŏl’s 50 Years of North Korean Art, published in South Korea in 2001, was a rare source that included the names of the leading industrial art designers who were active up to the 1990s. As such, the book serves as a compass in my own research to this day.

Ideally, South Korean researchers should be able to conduct fieldwork in the North, so that they can study the full picture, situating the arts and material culture within their proper social context. South Korean art historian and former director of the Cultural Heritage Administration, Yoo Hong Jun, writes, “the reason for deferring any judgements about North Korean art is that to reach true understanding, the best way is to hear from them directly” (1990). I agree wholeheartedly with this statement, and my inability to conduct fieldwork is a fundamental problem. Thus, my book cannot, as Yoo points out, be an assessment of North Korean design. Rather, I see its value as offering a new perspective on unfamiliar aspects of North Korean everyday life through the medium of design.

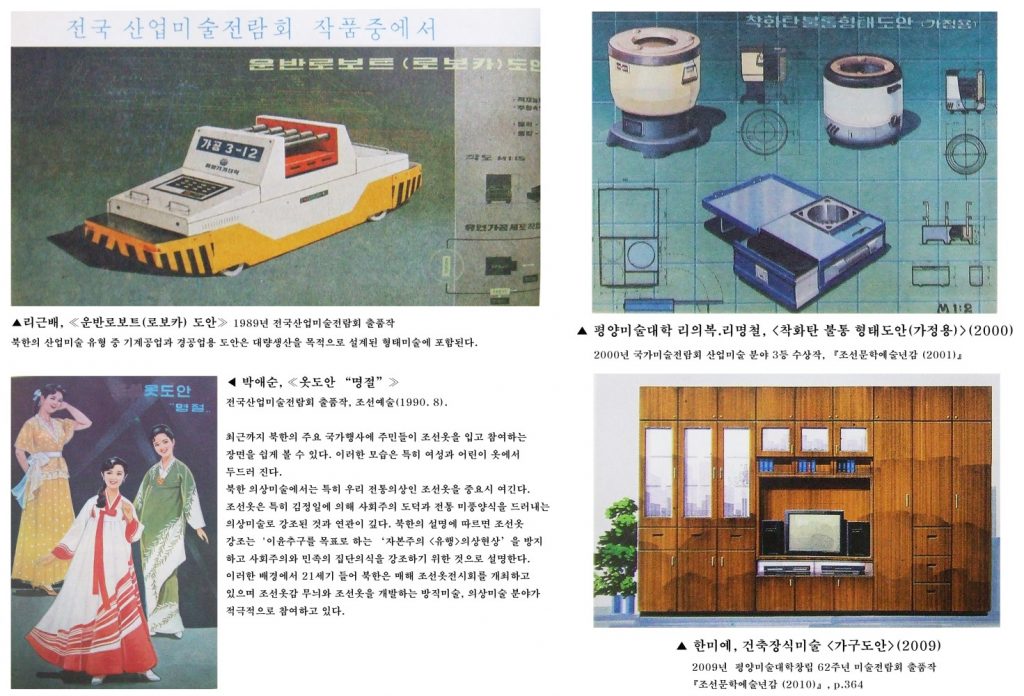

Examples of North Korean industrial art created from the late 1980s to 2000s. From Industrial Art as Design in North Korea: Vol. 1. 1945-1999 (2020): 28, Vol. 2. 2000-2018 (2020): 57.

Occasionally, there are those in possession of North Korean products such as beverage bottles, cigarettes, paintings, propaganda posters, stamps, and other items. However, most collectors have reservations about showing them publicly because of potential legal problems—whether in violation of the National Security Law domestically in South Korea or the various sanctions regulations in place internationally. This means that most of these sources cannot be used in research. While oral interviews of North Korean defectors has become commonplace in the study of North Korea, I have yet to come across anyone with experience in industrial art, out of the 33,752 defectors on record with the Ministry of Unification as of 2020. This suggests that while artists in general are rare among defectors, the emphasis on ink-style paintings called Joseonhwa also made the development of industrial art of lesser relative priority.1

However, an important turning point for North Korean industrial art came in 2012. The year marked the 100th anniversary of the Kim Il Sung’s birth and was pronounced the first year of a “Strong and Prosperous Nation.” The (North) Korean Artists Association declared that same year the “Golden Age of Industrial Art” and hosted a large-scale National Industrial Art Exhibition in the newly constructed Design Center. The exhibition put some 1,700 artifacts on display. With Kim Jong Un’s visit to the Design Center in April, North Korean industrial art received greater attention in the country and abroad. An article about the exhibition claimed that North Korean design dates back to the period of anti-Japanese guerrilla struggle and that the first works were designs by Kim Jong Suk (wife of Kim Il Sung).2 The truth is up for debate since art in North Korea is so heavily politicized. Nonetheless, my research clearly shows that North Korean industrial art has seventy years of its own independent history.

In 2018, Nicholas Bonner’s collection of North Korean stamps, wrapping paper, invitations, and other graphic design items were exhibited in South Korea. It was an opportunity to observe how others saw North Korean design. While some saw “out of fashion socialism” or “old-fashioned” aesthetics, the exhibition underscored the paucity of understanding that goes beyond the surface to appreciate the unique formative characteristics of North Korean design undergirded by years of aesthetic philosophy, collective design ethics, and economic and cultural policies.

North Korean industrial art lies at the intersection of art, economics, and politics. Not only does it reveal intimate aspects of people’s everyday lives and their attitudes toward material culture, but it also traces the political and economic debates, technological developments, and sociocultural trends in North Korea for the last seventy years. It is my hope that this research will prompt greater diversity and experimentation with new methods in the study of North Korea.

Hee Sun Choi is Adjunct Professor for the Graduate School of Arts at Chung Ang University in Seoul, Korea, and author of the two-volume study, Industrial Art as Design in North Korea (Seoul: Damdi, 2020).

References

Choi, Hee Sun. Industrial Art as Design in North Korea. Seoul: Damdi, 2020.

Kim, Soon Young, Chol Lee, Im Chol Lee, Hyung Jung Pak, In Kyou Jo, In Bok Ham, and Eu Jeong Hong. History of Korean Art. Vol. 2. Pyongyang: Social Science Publication, 1990.

Jeong Jong Yeo. “Accepting the Great Leader’s teachings and building on the foundation of Korean painting to put our art on the road to progress – on the occasion of the 15th anniversary of Comrade Kim Il-sung’s October 1954 doctrine to bring progress to Korea.” In Korean Art, 21-27. Pyongyang: Korean Federation of Literature and Arts Publications, 1969.

Yoo, Hong Jun. “Historical Materialism of North Korean Art.” In Art of North Korea, omnibus edited by Kim, Munhwan, Seoul: Eulyoo Publishing, 1990.

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.