Michael Berry examines Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary, a crucial text that documented the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China via an online blog, as an example of a “first look” and “future look.”

Michael Berry is a Professor at UCLA where is Director of the Center for Chinese Studies. He is the translator of Wuhan Diary and he recently completed a book-length account of the controversy surrounding the book.

edited by Lan Li

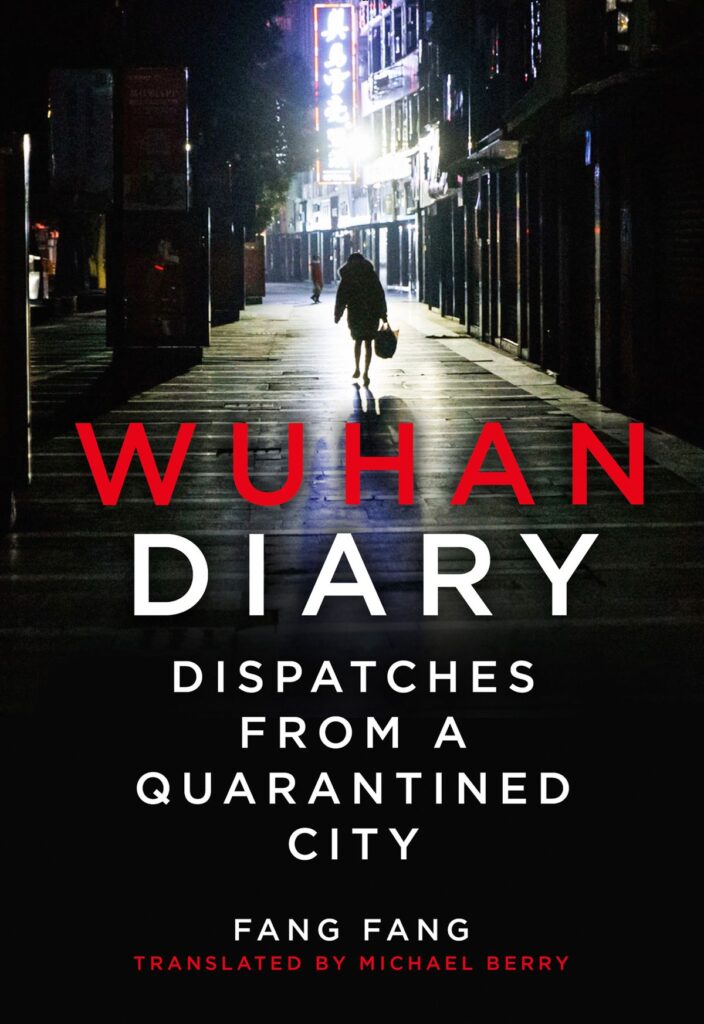

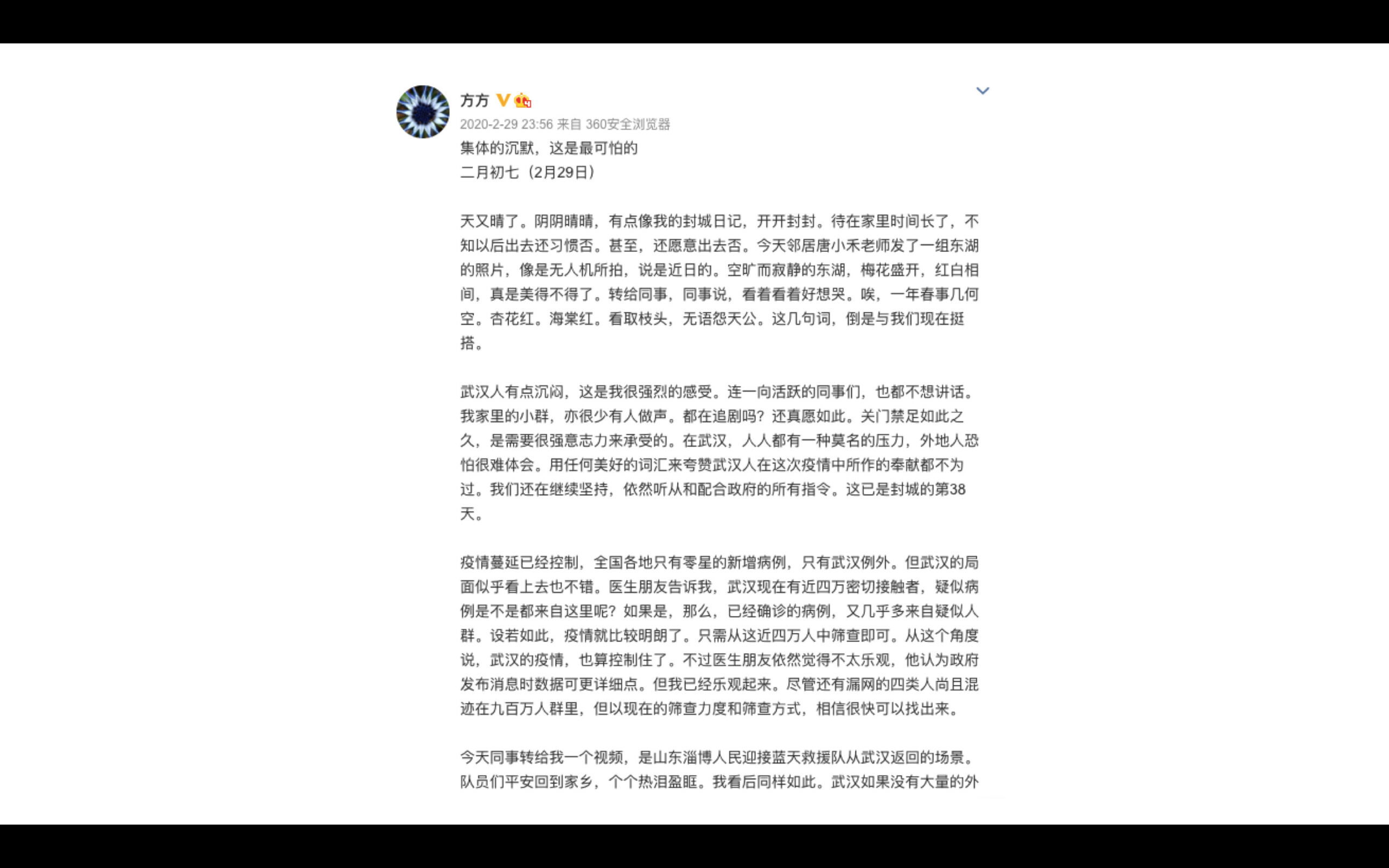

From January 25 through March 25, 2020, veteran Wuhan-based writer Fang Fang 方方 posted a series of online diary entries that would divide a nation and incite one of the most controversial cultural incidents in decades. Originally published on the Chinese social media platforms of Weibo and WeChat, Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City (武漢封城日記) chronicled the first city-wide lockdown due to COVID-19. The diary provided a space where more than 50,000,000 readers converged to understand what was transpiring in Wuhan during the height of the outbreak. It was there in the pages of Wuhan Diary that readers found someone who gave voice to their sorrow and rage; providing a bastion of solace and consolation. For those millions of Chinese readers during the early months of 2020, Wuhan Diary became the most important account of the unfolding tragedy. Fang Fang provided real-time reports on the nature of this strange new virus, sharing information she received from doctor friends on the condition at hospitals across the city, offering gentle suggestions to her readers, and crying with them during the death of Li Wenliang. Countless followers stayed up each night until the wee hours of the morning anxiously waiting for Fang Fang to upload her next installment online. She became the voice of Wuhan. As award-winning novelist Yan Lianke mused, “Imagine this: the author Fang Fang did not exist in today’s Wuhan…What would we have heard? What would we have seen?” For countless Chinese readers, Fang Fang became the eyes through which they navigated the darkest days of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. When Fang Fang began to write her diary, the virus still did not have an official name, residents still did not know how the virus was transmitted, and no one knew just how long the lockdown, which was the first of its kind, would last. The diary was very much a “first look,” a raw and unfiltered attempt to document, process, and make sense of the unprecedented events unfolding around her, which at that time must have felt almost cataclysmic. The role this first look played was multifold: Fang Fang’s diary functioned as an online clearinghouse of basic and breaking medical information about the virus, information that was of great interest to Chinese-speaking readers all over the world but carried an especially vital place for those fellow residents of Hubei province. As Zhu Jianguo observed, during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak, the diary actually played a direct and crucial role in raising widespread awareness about the virus and aiding China in its ability to take precautionary measures. This reveals the power of a “first look” to also wield potential for action, activism, and engagement.

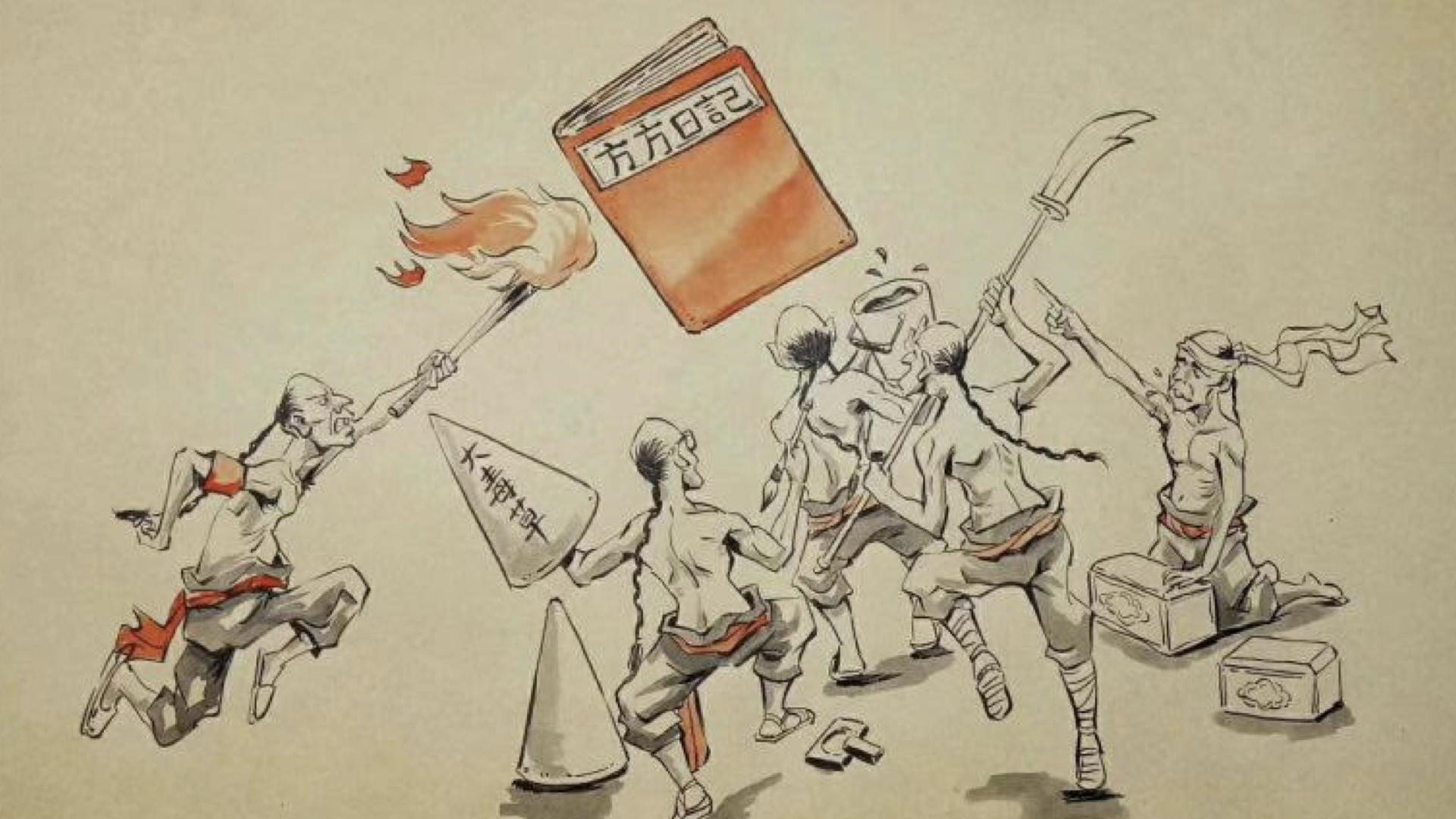

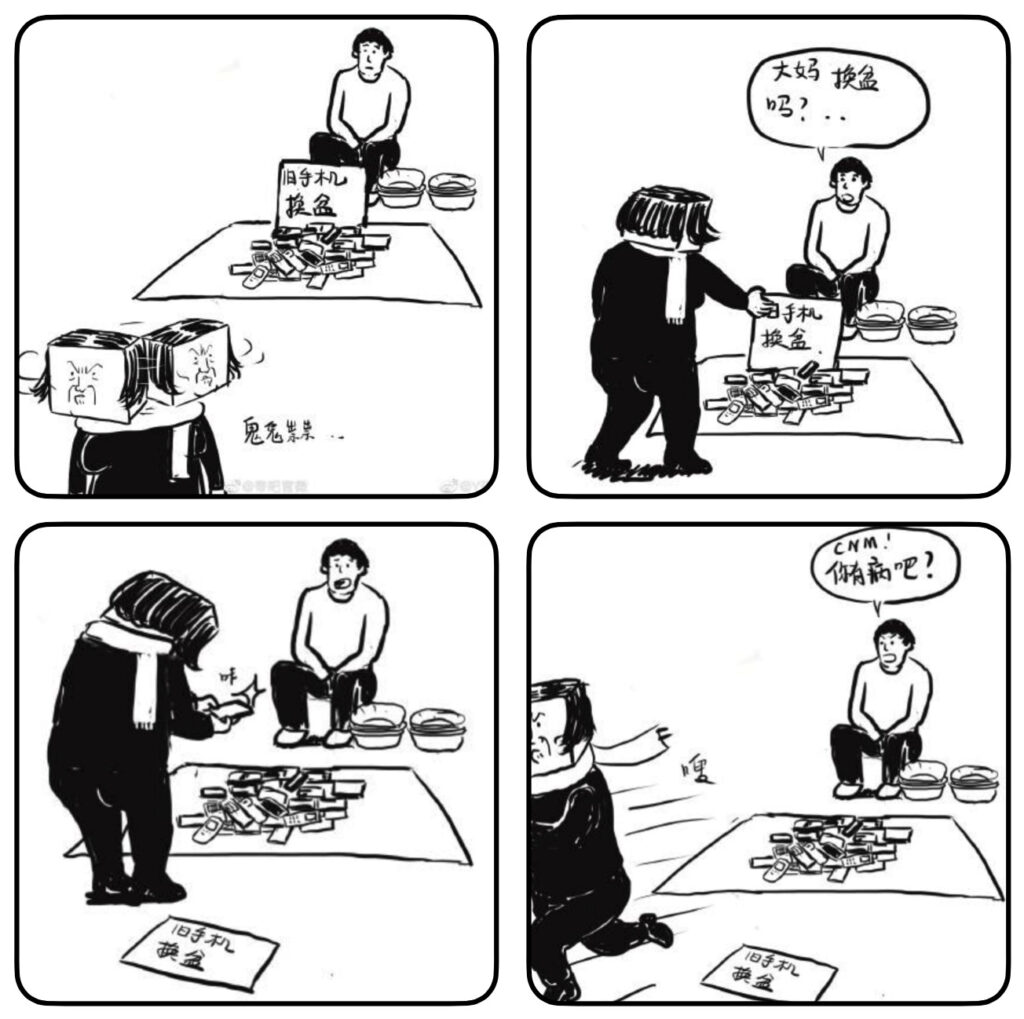

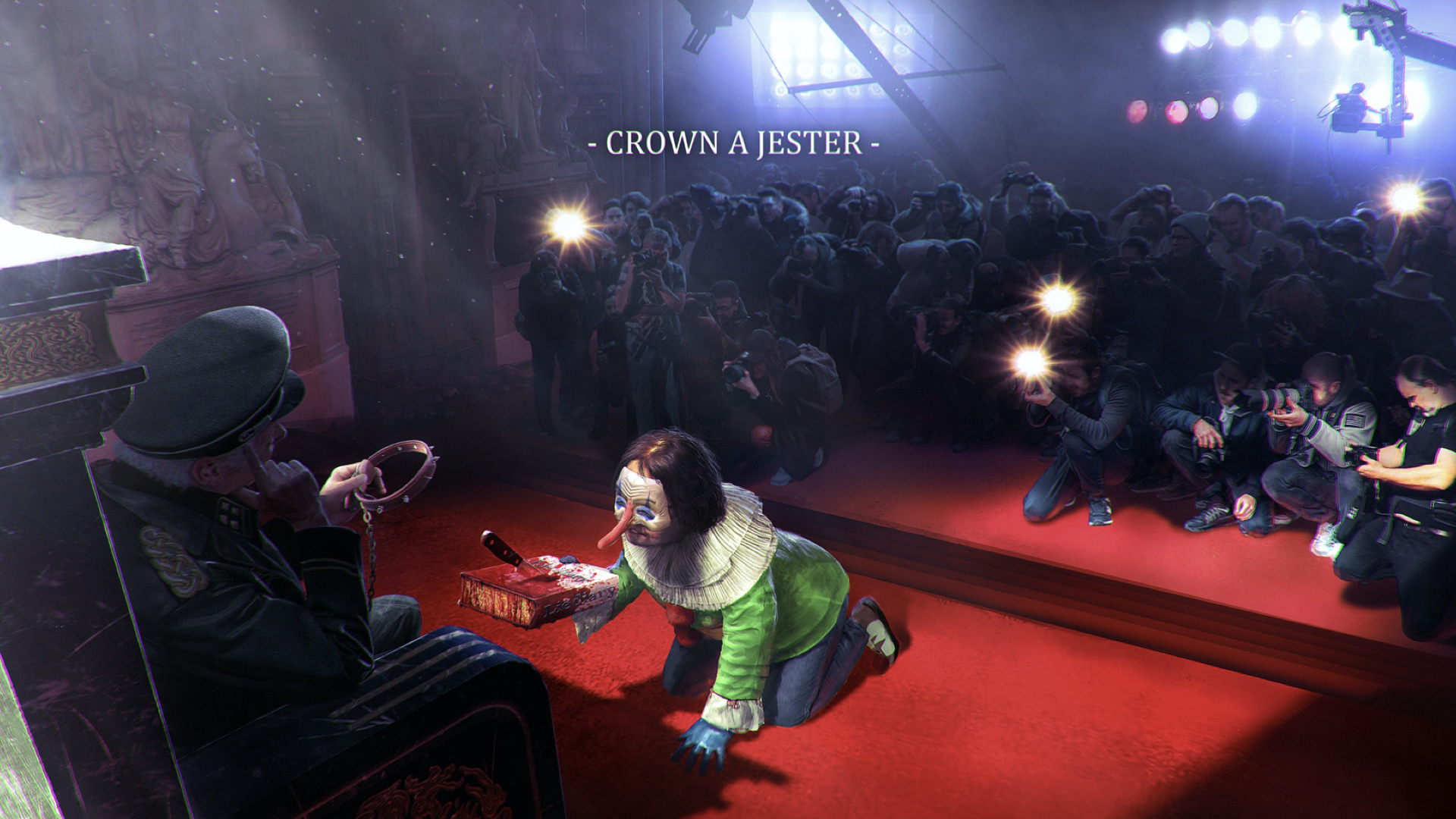

But in early April as news broke that Wuhan Diary was to be published in English and German, public discourse around the book underwent a radical shift. A sophisticated disinformation campaign was unleashed against the book which included a series of conspiracy theory-like accusations, anti-Fang Fang diss songs, political cartoons mocking the diary, hastily prepared academic articles attacking the book, thousands of online troll attacks, and even death threats. As the English translator of Wuhan Diary, I too was targeted with hate mail and death threats, which continue on an almost daily basis up until the time of this writing, more than eleven months later. Wuhan Diary, which was once embraced by millions has now been largely washed from Chinese social media, plans for a print version of the book in China were scrapped, and an army of more than a dozen “politically correct” diaries have risen up to take its place and tell the “official story.” By the time the English translation of Wuhan Diary was first published in e-book format in mid-May, which was remarkably quick by normal publication standards, I already felt like we were too late – the United States was already in the clutches of COVID-19. A year later, discos and theaters have reopened in Wuhan where life has more-or-less returned to normal, my home of Los Angeles has now become the new epicenter of the coronavirus, with some estimates that as many as one in three residents of Los Angeles County have tested positive for COVID-19. I silently wondered if there was an invisible “expiration date” tied to a first look; like daily headline news, was there a time in which Fang Fang’s account would no longer be relevant?

One year later, detractors of the book in China claim Wuhan Diary missed its mark: for them, the failure of the west in controlling COVID-19 has accentuated China’s success; rendering early mistakes (which Fang Fang highlighted in her diary) laughable as compared to the catastrophic losses suffered by countries like the United States. (Instead, nationalist Chinese trolls taunt me to write my own “American Diary” to document the mounting death toll and widespread infection rates in the United States). Others view Wuhan Diary as a historical document; an explosive of-the-moment record of how a global crisis first unfolded, an eyewitness account that offered the world its first glimpse of the damage this invisible virus is capable of unleashing and what a global lockdown might look like. It is this aspect of the “first look” which is particularly important: while the entire world would eventually adjust to life under lockdown, there is no way to recapture the fear, trepidation, anger, and feelings of confusion, isolation, loss and sadness that residents in Wuhan experienced during January and February of 2020. In this context, Fang Fang’s account provided a crucial archive of raw emotion, a record of responses, a museum of memories; it is this initial emotional response to COVID-19 which can never be reconstructed. In this sense, Fang Fang’s account is a crucial touchstone for future readers to understand the affective dimensions of the early lockdown. But for me, the most remarkable aspect of Wuhan Diary one year later is just how prophetic the book would prove to be. 2020 was not just the year of COVID-19, it was also a year of discrimination and racial tension, disinformation campaigns, fake news, conspiracy theories, political division, and online violence: and all of those keywords played a central role in Fang Fang’s diary. It is in this context that Wuhan Diary offered the world not only a “first look” at the novel coronavirus, but also a “future look.” Of course, there is an experiential symmetry in the ways that Fang Fang described experiences that seemed novel in January 2020 – like wearing facemasks, trying to reserve a delivery spot for online grocery deliveries, and the mundane aspects of life under quarantine, which she boiled down to “eating, sleeping, and binge watching” – however, on a much more profound level, Fang Fang was able to pinpoint the deeper fault lines extending out from behind the dark shadow of this virus.

The COVID-19 outbreak in the United States has been racialized on a number of different levels, from a sharp increase in instances of prejudice and hate crimes against Asian-Americans to the ways in which black and Hispanic communities have been disproportionately afflicted with this virus. But even before the United States had a single documented case of the coronavirus, Fang Fang had already discussed the overt discrimination against Wuhan natives throughout China. Early on in the outbreak in China, one of the first responses to what was then broadly referred to in Chinese media as “Wuhan pneumonia” was widespread discrimination against Wuhan residents living, working, and traveling in other parts of China. It was a cogent warning of how rapidly disease unleashes paranoia, fear, discrimination, and an urge to isolate and “quarantine” groups racial, ethnic, and regional groups that are labeled as “infected.” She also made it clear that the virus itself does not differentiate when it comes to race or class; as early as January 28, Fang Fang wrote “the virus doesn’t discriminate between ordinary people and high-ranking leaders,” advice that those who attended the White House Rose Garden superspreader event on September 26 would have been well to heed. Fang Fang also wrote at length about the politicization of the virus in China, but she certainly could have never predicted the obscene level of political polarity that would coalesce around the simple commonsense preventive measures like the wearing of facemasks in the United States. According to Fang Fang’s account, she first wore a facemask on January 18, 2020 when she visited a friend in the hospital. At the time, there were still no official announcements about an outbreak, yet in response to rumors of a new SARS-like illness spreading in Wuhan, Fang Fang began to don a mask. Please let that sink in: Fang Fang is willingly wearing an N95 mask on January 18 long before the word COVID-19 has even been coined. There was very little information about what this virus was, how it spread, who was at risk, yet out of an overabundance of caution, Fang Fang begins wearing a mask. The United States death toll from COVID-19 has now surpassed 465,000 people with more than 27 million cases. We know for certain that wearing masks helps prevent the spread of COVID-19 and health officials have repeatedly stated that infection rates would plummet if 80% of Americans wore a mask, yet many citizens not only continue to refuse to wear masks but we have even seen the absurd rise of the “anti-masker movement,” from lawmakers in Florida suing their state over mask mandates in July, 2020 to an anti-mask “Freedom Rally in January, 2021 in Los Angeles! Fang Fang described the desperation of Wuhan residents dealing with an early shortage of facemasks while nearly a year later in America we still see daily videos on social media of Americans raging against masks.

Fang Fang’s diary also traced the disturbing intersection of COVID-19 with disinformation campaigns, fake news, and conspiracy theories. As online attacks against the book mounted, Wuhan Diary became pulled into an increasingly complex vortex of conspiracy theories involving everything from the US-China Trade War to the origins of the COVID-19 virus. Along the way, the wild accusations ranged from allegations that Fang Fang and I were CIA agents to the diary being part of a sophisticated anti-China plot to damage the nation’s global image. A year later, the theories have not only failed to die down, but they have become even more unbridled, with Chinese social media posts in early 2021 now blaming Fang Fang for the United States’ failure to control COVID-19! (They claim that Fang Fang’s calls for Chinese government accountability lulled the US into a state of complacency, thinking that the outbreak as result of human failure). The protracted nature of the attacks against Wuhan Diary also speaks to the continued relevance and power that a “first look” can wield, which in this case went on to shape so much of the subsequent discourse about the Wuhan outbreak. The conspiracy theories that arose fueled waves of online hate and the aforementioned death threats, all of which were further exacerbated by the fact that millions of people were out of work, locked down at home, angry and frustrated. Imagine my surprise when, a few months later, I began to see a nearly identical pattern of online hate, disinformation, and conspiracy theories sweeping the United States – from QAnon to “Stop the Steal” –with many of the most egregious lies echoing through, if not emanating from, the highest office in the land.

A year later, the meaning of Wuhan Diary lies not only in its account of COVID-19, but also in the fierce public and online debates that surrounded the book. These debates circulating around Wuhan Diary became a public referendum on the very nature of civil society in China. It was not about Fang Fang, but about what kind of country Chinese citizens wanted for themselves: A nation where someone can publish a diary without fear or threats of reprisal? Or a nation where only one “politically correct” version of truth is permissible? It was a war between those who advocated for a more open and pluralistic society and a “you’re with us or against us” faction that viewed the world in simplistic black-and-white terms. The debates over this issue in China were fierce and unprecedented; I received numerous letters from Chinese netizens who told me they had stopped talking to friends or relatives due to disagreements over Wuhan Diary. The book became a lightning rod issue that was literally tearing families apart. A few months later, the United States would also be torn apart as it too navigated similar questions about civil society, which would go from online forums and presidential Twitter feeds to the very halls of the Capital Building during the January 6 insurrection.

Finally, 2020 was also a year that stood out for the stunning lack of accountability for those who mishandled the virus. One of the most remarkable aspects of Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary are her repeated appeals for specialists and officials who mishandled the outbreak to stand up, take responsibility for their mistakes, apologize, and resign. In Wuhan Diary, Fang Fang raged against those officials who suppressed information about the virus early on, public security personnel who muzzled the whistleblower Li Wenliang, and the public health officials who claimed person-to-person transmission of the coronavirus was not possible. As Fang Fang writes: “who were the leaders that in order to save face decided to twist the truth when reporting to their superiors and hide the truth from the public, who was it that put political correctness above the lives of our people, how many people contributed to this disaster? Whoever had a hand in this should take responsibility: the people need someone to assume accountability. At the same time, the government should urge officials from various departments whose actions misguided the public, leading to massive numbers of deaths, to resign.” Make no mistake, China did mishandle some details of the novel coronavirus outbreak early on in Wuhan; this is now part of the public record. The police officers that wrongly accused Li Wenliang of “spreading rumors” publicly apologized. And once the central government took control of the “battle against the virus,” they quickly adopted a clear and strong policy that effectively flattened the curve and ultimately squashed the outbreak in China. Their actions may have fallen short by Fang Fang’s standards, there was some degree of accountability in China. Numerous officials were dismissed from office or demoted as a direct consequence for their mishandling of the COVID-19 response in Wuhan. As the United States gazes down the black hole of a dismantled pandemic response team, broken CDC test kits, chronic shortages of PPE and ventilators, delays in testing even when it was declared “anyone who wants a test can get a test,” a stunning lack of federal policy concerning COVID-19, a flawed vaccination rollout, a cesspool of lies, distraction, and disinformation, and a mounting death toll we must ask who will hold our leaders accountable? If Fang Fang, writing under an authoritarian regime, under constant attack by thousands of internet trolls, was able to demand that her government live up to a higher standard of truth, transparency, and accountability, what is our excuse?

A year on in China, Fang Fang’s initial calls for accountability have been all but forgotten, buried under a smokescreen of attacks and threats against the author. Thanks to one of the most sophisticated and protracted personal attack campaigns waged against an individual, Fang Fang is now alternately referred to as “the witch of lies,” a “traitor to China,” a “secret CIA agent,” and an entitled, out-of-touch gongzhi (a derogatory reference to “public intellectuals”) who exploited the Chinese people to gain fame and profit. Here in the United States (and so many other western nations that utterly failed when it came to the tests that COVID-19 presented to them) will this too be our “future look”? A long, dead, empty stare that, in the face of startling displays of inaction, ineptitude, and injustice offers only silence, complacency, and cries of “victory” in our battle against the virus.

If you are interested in submitting an essay, video, work of photography, or other creative work to the First Looks series, please contact Bishnupriya Ghosh and Michael Berry at: [email protected] and [email protected]

Music by MOIZ.