Carlos Rojas discusses first responses to COVID-19 as recorded by an archival project created by Duke Kunshan University (DKU), a partnership between Duke University and Wuhan University.

On March 3, Duke University’s John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute and Duke Kunshan University’s (DKU) Humanities Research Center co-hosted a workshop on the topic of the COVID-19 outbreak and DKU’s response.[1]

Established in September 2013, DKU is a U.S.-China partnership between Duke University and Wuhan University. DKU opened to MA students and non-degree “semester-abroad” undergraduates in Fall of 2014, and in Fall of 2018 the university accepted the first cohort of students for its new four-year undergraduate degree program. Although DKU is located roughly halfway between Shanghai and Suzhou, one of its two partner institutions, Wuhan University, is located in Wuhan, which of course was the epicenter of the initial COVID-19 outbreak.

When DKU paused for its pre-scheduled two-week Lunar New Year winter break on January 24, 2020, accordingly, the university was in its sixth year of operation, while the undergraduate college was in only its second year. At that point, the university had approximately 725 students, of which approximately 35% were international students hailing from over forty different countries. After the January 23 announcement that Wuhan and other cities in Hubei Province would be imposing strict lockdowns on all residents, like other universities throughout China, DKU decided initially to extend its two-week winter break.

Soon, however, the university resolved to send all but a small minority of students and faculty home, and to restart classes entirely on-line. With this decision to shut down the DKU campus, most of DKU’s students returned either to their homes either in China or in their home countries—with a small group of students permitted to remain on campus either because their homes were in Hubei, which was under near-total lockdown, or because international travel to their home countries was not feasible. Meanwhile, a cohort of DKU faculty relocated temporarily to Duke University’s campus in Durham, NC—and it was in a building at Duke that the March 3 COVID workshop was held.

The March 3 workshop was actually a double event, with the first session held virtually over Zoom, followed immediately by a second session held in a conference room on Duke’s campus. For many of the participants, this was not only their first fully on-line workshop but also their final in-person academic event for many months (coincidentally, on the day of the workshop, North Carolina reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19, and within two weeks all Duke classes had been moved on-line and Duke faculty had been instructed to “cease small-group and individual meetings effective immediately”).[2] The workshop brought together scholars from different disciplines to discuss the COVID-19 outbreak (the WHO would not officially designate the outbreak a pandemic until eight days later), including not only the outbreak’s general epidemiological, political, economic, and socio-cultural implications, but also how it had specifically impacted the DKU community.

Among the presenters at the workshop were DKU faculty members Benjamin Bacon and Weijing (“Vivian”) Xu, who used the occasion to discuss the COVID-19 Memory Archival Project, which they had officially launched on March 1, just two days earlier. Developed under the auspices of the Health Humanities Lab, one of several humanities labs sponsored by DKU’s Humanities Research Center, the COVID-19 Memory Archival Project offered an on-line platform for users to post multi-media archives relating to the epidemic—or, as Bacon and Xu put it, “to preserve experiences through a memory archive, but also through personal narration, bring comfort, peace, reflection and healing to participating individuals.” More specifically, the project uses the ArcGIS StoryMaps digital platform, which permits a relatively seamless integration of text, image, audio, and video material. Currently (as of early April, 2021), twenty-one storymaps have been uploaded to the site, and although most of the contributions are from students at either DKU, Duke University, or the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), in principle anyone can upload a project (and the site even contains a “COVID-19 Memory Archival Tutorial” for users on how to create their own StoryMap).[3]

In August 2019, the Esri GIS mapping software company had introduced a new “collections” feature to its multimedia ArcGIS StoryMaps platform (which itself had been introduced only a month earlier). As Esri explains, this new feature can be used to “group stories together and share or present them as a cohesive, easily navigable set.” When, in early 2020, Bacon and Xu were looking for a platform on which to publish different users’ perspectives on the COVID-19 outbreak, this “collections” feature lent itself well to their needs. Meanwhile, a year later, in October 2020, Esri highlighted the DKU pandemic project as an exemplary illustration of what could be accomplished with the platform:

This extraordinary aggregation was spearheaded by Benjamin Bacon, associate professor, and Weijing (Vivian) Xu, assistant professor, both of the Media and Arts program at Duke Kunshan University, the campus of which is located near Shanghai, China. Members of the Duke Kunshan community were invited to create stories recounting their experiences during the COVID pandemic. Submissions range from relatively conventional narratives to highly subjective and original depictions of the anxiety and isolation brought on by the crisis.

As if to underscore its support for the project, four months later, a group identified as “Esri’s StoryMaps team” added its own StoryMaps to the site. Titled “Mapping the Covid-19 Pandemic” (January 25, 2021), the StoryMaps was authored by Ross Donihue and Cooper Thomas, who both work as cartographers and designers for ArcGIS StoryMaps, and it brings together a variety of useful resources on the history and current status of the pandemic (see image 1). These resources, many of which are self-updating, include a Johns Hopkins University world map of “confirmed and presumptive coronavirus cases at the sub-national level,” a self-updating tabulations of global confirmed cases and deaths (also from the Johns Hopkins University), a population density map of areas in and around Wuhan,” a map of quarantined cities in Hubei Province (scaled by population) accompanied by a short narrative outlining the chronology of the various quarantines implemented in the region, and so forth.

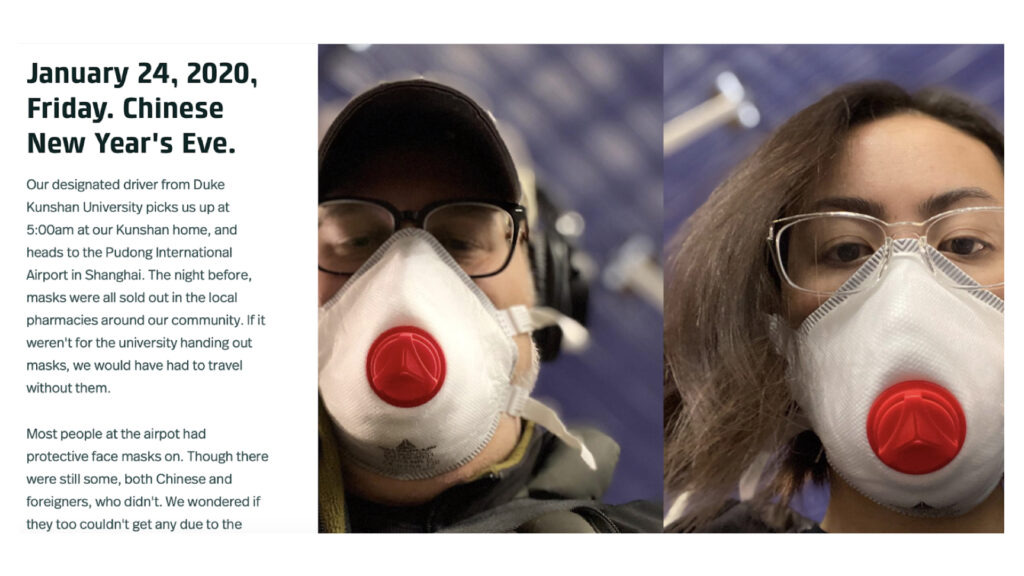

If Donihue and Thomas’s “Mapping the COVID-19 Pandemic” storymap illustrates some of the data-intensive capabilities of the StoryMaps platform, the storymap designed by Bacon and Xu illustrates some of the platform’s more personal—and even intimate—possibilities. Titled “Our Story: Kunshan to Durham” (April 27, 2020), the storymap opens with a pair of selfies of the authors (both wearing protective masks) at the Shanghai Pudong airport, with a narrative of how they left China Kunshan on January 24 (Lunar New Year’s eve) to return to the US for the winter break (see image 2). They describe how their time with family in Wisconsin “was shadowed by the uncertainty of the development of the virus. Benjamin and I were glued to our phones, checking updates on confirmed cases and fatality rates, reading the news from both inside and outside China, checking up regularly on family, friends, colleagues and students.”

Accompanying this portion of the narrative is a dynamic map of China (compiled from images published on a WeChat mobile app) of the viruses rapid spread through China) and an interactive map of the world that contains data relating not only to COVID-19 but also SARS, H1N1 (“swine flu”), and Ebola. The map and accompanying charts were developed by Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering, and are auto-updating, continuing data that is current up to the present moment. Bacon and Xu describe their reaction when it became clear that most major airlines began cancelling all flights to China, and it became clear that they would not be able to return to Kunshan as planned.

What follows is an intimate, first-person photo-essay of the couple’s trajectory in the US over the next several weeks, interweaving intimate accounts of their experiences with thoughtful reflections on the broader crisis (including discussions and pictures of Vivian’s parents in China, and a social media meme urging Chinese residents not to abandon their pets out of fear of the coronavirus). Eventually, the couple reveals that Duke University had offered to house them until it was possible to return to China.

The earliest cluster of pages uploaded to the Memory Archival Project site are ten student projects published between March 20 and March 23, 2020. These pages adopt a wide variety of different approaches, from traditional storytelling to more innovative amalgams of information and narrative. For instance, in “Comments Under Coronavirus News: A Look at the Chinese and American Media” (May 24), Hao Tan offers a bilingual archive of comments posted on Youtube and Weibo (a popular Chinese microblog platform, similar to Twitter) in response to news items relating to the pandemic (the news items are culled from six different news outlets in China and the US, with the three US news outlets representing an array of different political orientations).

For each news item, in addition to a screen shot of the original news item Hao Tan archives sample comments posted by web users in response to the news in question (translating the English comments into Chinese, and vice versa) (see image 3). The result is a fascinating glimpse at some of the grassroots reactions to the pandemic in China and the United States, recorded in real time.

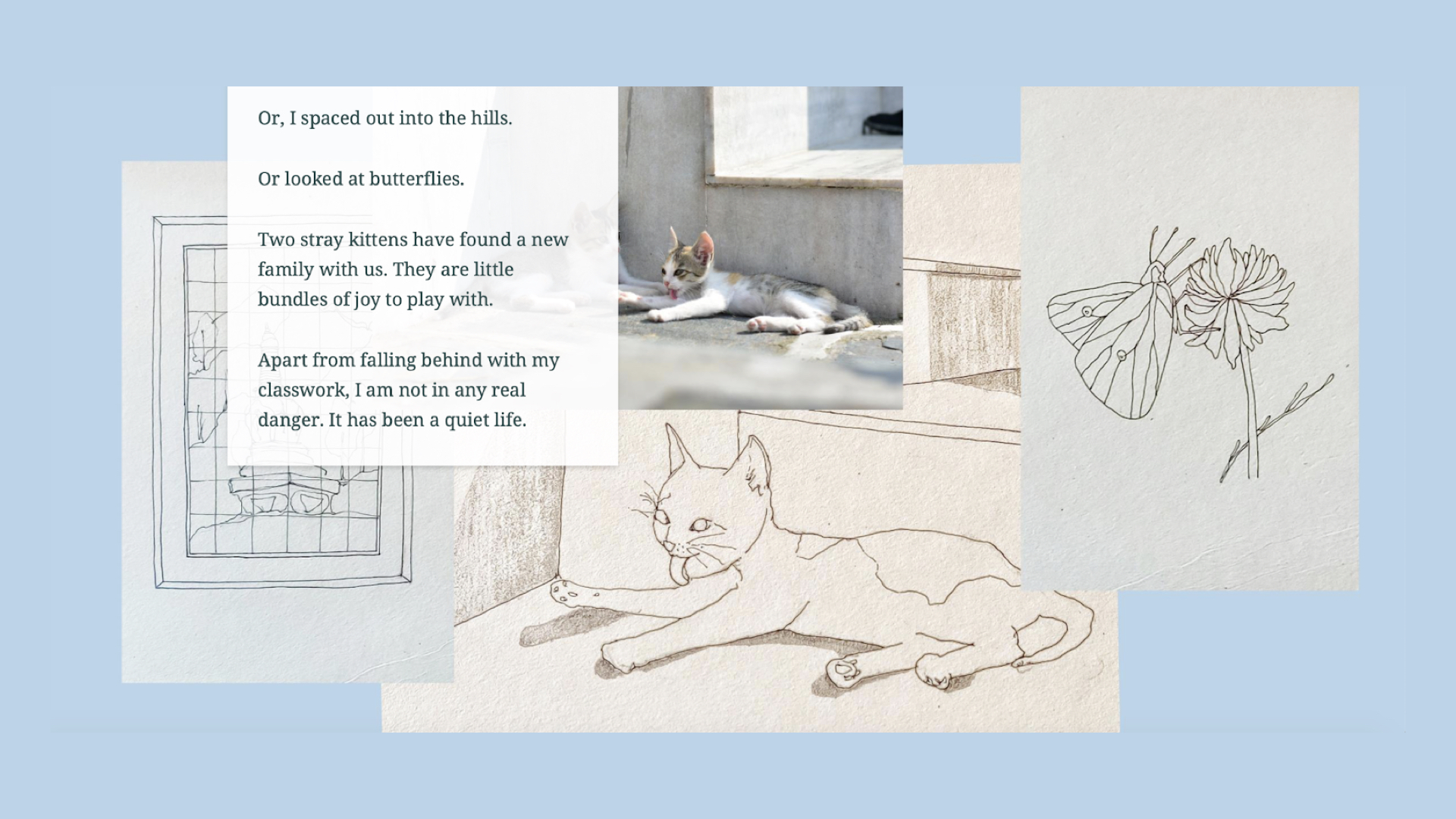

In “A COVID-19 Story From Nepal: Different Perspectives to a Pandemic” (May 17, 2020), Anisha Joshi details her return from Kunshan to Kathmandu. The project opens on a personal note, with Joshi noting that the pandemic was “the most I have ever cooked for my family” (since she was home, and her father and brother were away). With text playfully set against a world map detailing the approximate locations of Joshi’s friends, followed by hand-drawn images of kittens (see images 4 and 5), Joshi adds that,

When not panicked about the world news or deadlines, I decompressed by keeping in touch with my friends, scattered across five time zones.

Or, I spaced out into the hills.

Or looked at butterflies.

Two stray kittens have found a new family with us. They are little bundles of joy to play with.

Apart from falling behind with my classwork, I am not in any real danger. It has been a quiet life.

The project then quickly transitions to a thoughtful reflection on how the pandemic has underscored the precarious position of Nepali migrant laborers, both in Nepal and around the world. Combining commentary with evocative images and a world map detailing the number and location of Nepalis known to have been infected by the virus.

In “Advance! Advance at all Costs!! Lights and Shadows of China under Coronavirus” (March 23, 2020), Linxi Li borrows a line (originally uttered by a deeply flawed character) from Chinese SF author Liu Cixin’s novel Three Body Problem trilogy. This line subsequently became a meme in Chinese social media during the COVID crisis, and Li uses it to question what is the “cost” at which China’s recent rapid development has been attained. Li then proceeds to use this and other cultural references (including many borrowed from Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem) to analyze the initial coronavirus outbreak in China and the Chinese government’s response to the crisis. Li considers both at the government’s extraordinary accomplishments (including building entire new hospitals in mere days) as well as its deficiencies (including its attempts to restrict public dialogue about some aspects of the outbreak). Li then offers a more personalized description of how “I went back to Xi’an to avoid the more and more severe situation in Beijing. Beijing Western station is under tightly control. This antigas mask gave me strong sense of safety.” He then concludes with a quote from the poet Ai Qing, which he translates as “Why are my eyes always brimming with tears? Because I love this land so deeply,” noting that the Chinese term he translates as “deeply” actually refers to a more complicated, ambivalent feeling in this poem. But I cannot find a better word to translate.

Now I truly understand what this poem means and how does the poet feel when he wrote this poem.

I love my country.

我爱我的祖国.

Appearing bilingually in bold and extra-large font, this final declaration is undoubtedly sincere, yet is also evidently inflected with the same “complicated, ambivalent feeling” that Li identifies in the Ai Qing poem (see image 6).

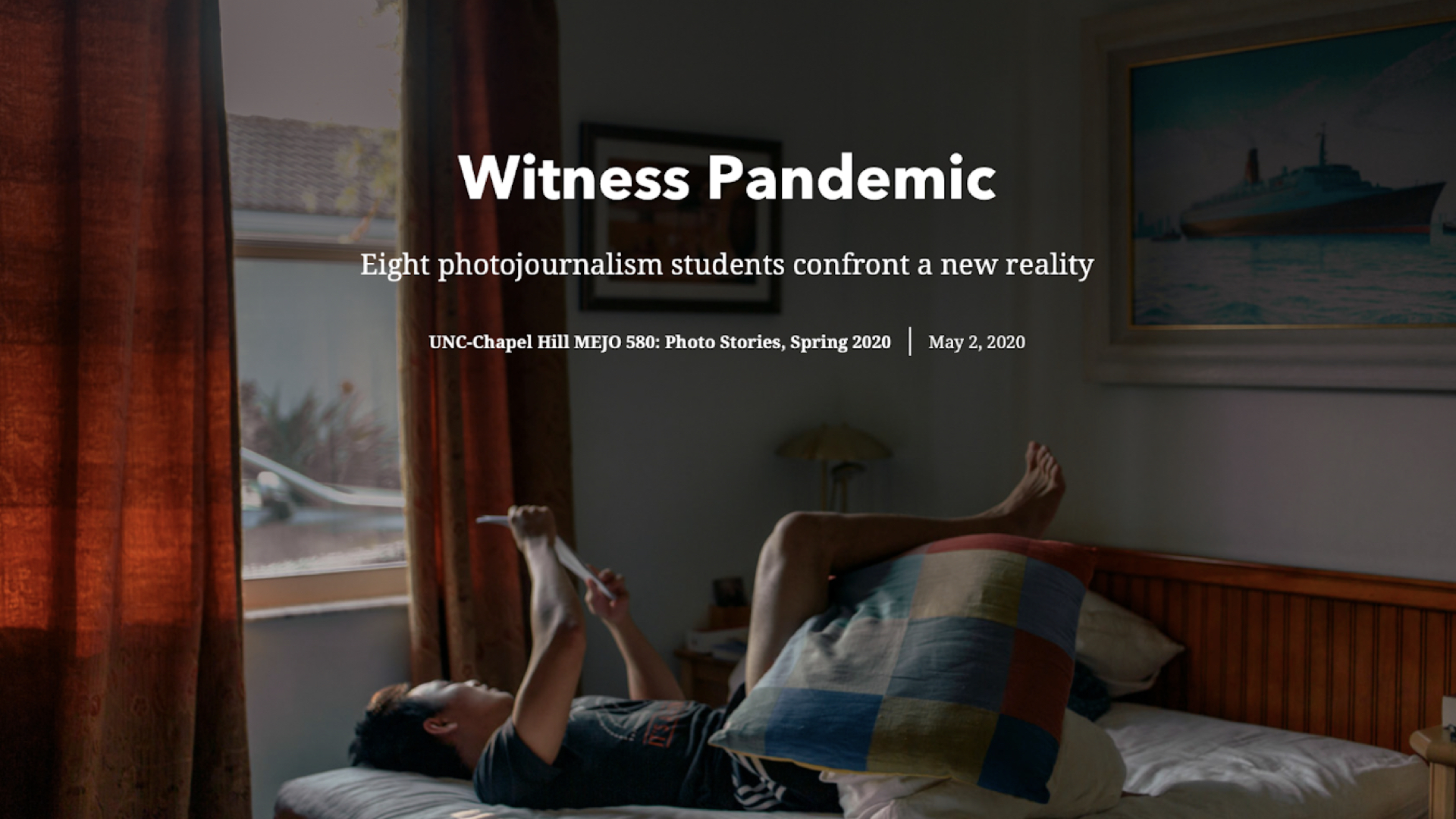

In addition to DKU affiliates, the COVID-19 Memory Archival Project site is also open to submissions by other users. For instance, “Witness Pandemic: Eight Photojournalism Students Confront a New Reality” (May 2, 2020) is a collaborative photo-essay developed and posted by students who at the time were enrolled in a journalism class on “Photo Stories” at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (see image 7). As the storymap explains, in late March UNC announced that all classes would go on-line, followed shortly after by another announcement that all university residence halls would close, and asking students to return to their permanent homes. Scattered across the country from Florida to California, the students in the “Photo Stories” class proceeded to record their experiences and observations on an Instagram feed, a portion of which was later uploaded to the COVID-19 Memory Archival Project site. Interestingly, apart from a short introductory statement, the “Witness Pandemic” storymap, like the students’ original Instagram feed, consists of only images, with the only words being the textual fragments that happen to appear within the photographs themselves (e.g., in church signs, graffiti, and so forth).

One of the most recent projects on the site, meanwhile, is a photo essay by DKU graduate student Sage Wyatt, who had been traveling in Japan when his return to Kunshan was derailed by the pandemic. Instead, he went back to the US, and his project, titled “Moving On: My Journey Across Five Homes in Very Uncertain Times” (January 21, 2021), chronicles his peripatetic existence after returning to the US. As Wyatt puts it,

I moved back to the US, where I incorrectly thought I would be at less risk of the virus. After moving, I felt inside that I had lost everything like I had given up on my dreams. And then I moved again, and again, and again. The year 2020 was an entirely unsettling time for me, but I learned to find small joys in the beautiful things I saw along the way. Actually, my life was so filled with goodness and joy. My fate was not misfortune. This collection is a series of beautiful moments I had while uprooted and uncertain.

Wyatt then chronicles—with a combination of photographs and short commentaries—the five locations where he resided after returning to the US. For instance, the first photograph is a sharply angled image of a white picket fence, with the caption:

In my first house back in the US, I literally lived behind a white picket fence, the symbol of the American Dream. If I was living in a dream, why did I feel like I had lost so much? I was living a dream that was not my own.

The storymap’s final image, meanwhile, is of a truncated message on a digital expressway sign that reads “IF YOU HAVE RECOVERED FROM COVID,” with a caption that reads, “I have settled, and I begin to imagine an end. But somehow as ‘the end’ draws nearer, the future feels even more uncertain” (see image 8).

Although this line technically marks the end of Wyatt’s storymap, it explicitly underscores the fact that the story mapped in his storymap is one that lacks a clear conclusion. Similarly, the nonlinear, open-ended nature of the Covid-19 Memory Archival Project is one that resists the possibility of closure—just like the still-ongoing pandemic itself

NOTES

[1] Together with DKU professor James Miller, who organized the conference, I am one of the co-directors of the DKU Humanities Research Center.

[2] Revised versions of many of the essays presented at these two workshops were subsequently published in James Miller, ed., The Coronavirus: Human, Social, and Political Implications (Singapore: Palgrave, 2020).

[3] As Bacon and Xu explain, “The site is open to new contributions. For the most part, the review process is open but sometimes we provide some feedback. The majority of submissions have been from DKU, Duke, or UNC students. After they have published their storymap to the ESRI online system, they send us the link to their story and we add that to the collection” (private communication, April 3, 2021).

__________

If you are interested in submitting an essay, video, work of photography, or other creative work to the First Looks series, please contact Bishnupriya Ghosh and Michael Berry at: [email protected] and [email protected]

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.