In the Fall of 2023, Ph.D. students in East Asian Studies and Near Eastern Studies at Princeton launched the East Meets East film series. Curating films from multiple locations across disciplinary and national boundaries, East Meets East aims to interrupt compliance with the colonial knowledge system and ongoing violence against occupied subjects.

Vero Chai

East Meets East is an ongoing film series organized by two Ph.D. students at Princeton University—Heejoo Kim in East Asian Studies and Xinyi Wei in Near Eastern Studies. Since its launch in Fall 2023, the duo has been presenting a film on campus every week based on their carefully curated program, and each screening has been followed by an open discussion with the attendees. Their inaugural theme was “Re-Orienting Desire,” deriving from the two departments’ shared conversations on orientalism and the organizers’ interest in “queering” as a critical method and framework. Seeing film screening as a “critical event for scholarly experience and possible channel for group practices of rethinking academic boundaries,” Heejoo Kim and Xinyi Wei reflect on the first run of East Meets East, and how the series itself had to be “re-oriented” in the time of Palestine.

Vero Chai (VC): How did you arrive at “Re-orienting Desire” as the inaugural theme of the series? And how does each title in the original lineup fit into this theme?

Heejoo Kim (HK): Xinyi suggested the theme. From my end, I had a broad idea that the inaugural theme should touch upon a critical concern shared by both departments. Edward Said’s Orientalism was, of course, a departure point. Another consideration was the matter of representation. Both organizers had a similar frustration at the planning stage about the narrow ecosystem of Princeton’s cinema community. Not to mention, Princeton does not have a film department, so there are few opportunities to access Near Eastern or East Asian films. I was also interested in theoretical inquiries that we can pull out from this series. “Queering” seemed a perfect way to encapsulate our project since it deviates from canons, disciplinary divisions, and eccentric archives.

Xinyi Wei (XW): Whether you want to call it Middle Eastern Studies or Near Eastern Studies or even Oriental Studies, the field that I am in always has had a crisis in definition. The very history of the terms and establishment of area studies departments imply deep entanglement with European and U.S. imperialism. If we are being really generous with the intellectual scope of the “near east”, it could go as far west as Spain (al-Andalus) to China in the east. To be in this field suggests the necessity of being aware of where one is positioned, and to where one is looking. I have a funny anecdote that when my parents were in Istanbul, they called it “the West” because, well, it was west of China. I hope the film series, by alternating films from NES and EAS each week, can generate and prolong this moment of critical awareness of being disoriented.

VC: What were some of the recurring thoughts or questions during the post-screening discussions? Which film(s) in particular stood out in framing these conversations?

HK: Recurring questions are these two: what is “national cinema,” and “What is queer about this film?” For me, these two questions are more theoretically inculcated questions. Both the idea of nation and cinema become the ambit of reconsideration. The questions about queer brought more diverse reactions. Queering is again a more expandable theoretical method and category. Deviation, eccentricity, and even “low,” according to queer scholar Jack Halberstam, were the matters of concern with how to rebut the given idea of a feature film, whatever that means. From the East Asian studies side, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Tropical Malady was the one. The film has an eccentric plot comprising two chapters. The first chapter seemingly touches upon queer subjects, the latter not much. Discussions pulled out precisely the question’s point. Is it Thai cinema? Is it a queer film? We also attempted to push back against a more logocentric interpretation of the plot, trying not to think about whether this film’s story makes sense.

XW: Saim Sadiq’s Joyland also offered opportunities for discussing what makes a story queer. Joyland seemingly centers on the love affair between a cisgender man and a transwoman in contemporary Pakistan, but Saim Sadiq has publicly resisted categorizing the film as a queer story.

VC: You’ve described the name “East Meets East” as a parodic response to the “East Meets West” trope, as well as an emphasis on the collaboration between your disciplines, East Asian Studies and Near Eastern Studies. Can we also take this as a method? How do watching and discoursing on East Asian language films through the lens of Near Eastern Studies – and vice versa – illuminate the otherwise unnoticeable aspects of those films?

HK: This is an interesting question. But the number of curated films is not to draw a concrete comparative method to approach East Asian Studies and Near Eastern Studies. There are methodological differences between organizers, perhaps relevant to the disposition in each discipline. I tried to touch upon theoretical queries about national borders and subjectivities. Considering my study’s relevance to the film series, media literacy for reading formal components or audiovisual structure has been my particular interest in the discussions.

XW: Personally, I’ve always been amused by people’s reaction when I tell them I am in the department of “Near Eastern Studies” (Just recently I had to explain that to the immigration officer at SF airport, which was a lot less fun). My previous education at New York University in Abu Dhabi always encouraged global, comparative analysis and emphasized “provincializing Europe,” so East Meets East just made sense to me as a project. I find the framework crucial in preventing scholars from falling into the trap of essentialization and Orientalization. As area studies departments, both EAS and NES are interdisciplinary in nature, so Heejoo and I come from different disciplinary backgrounds. I tend to focus on the socio-historical contexts of the films, and I am especially interested in exploring film as pedagogical tools. In the first half of the series, it struck me that from Farewell My Concubine to Joyland to The Blue Caftan, there was this common story/trope of the dead wife who was married to a queer man. It is not always the case that the wife has to die for the queer man to be happy; Farewell My Concubine and Joyland both ended in tragedy. But is this the tragedy of homosexuality or the tragedy of heterosexuality, or something more, like a critique of patriarchal norms overall? The Chinese fifth generation directors such as Zhang Yimou used to be criticized by the public for catering to “western” aesthetics and imagination when their films were critical of Chinese history. Can we transcend these critiques out of the geographies of China, Pakistan, and Morocco? If so, how? These were the questions on my mind.

VC: Could you tell us about how you came to the decision to replace the last few screenings with Palestinian films? Both of you had already been actively participating in various walk-outs and protests in support of Palestine, moving from Princeton campus to the White House. What do you find particularly significant about bringing that work into the more intimately intellectual space of film screening and discussion?

XW: We learned in the beginning of the week that there was a walk-out scheduled to take place on Thursday, November 9th, which is the day our screenings take place. We originally planned for Kamran Heidari’s My Name Is Negahdar Jamali and I Make Westerns. While we were waiting to hear details of the walk-out, I was leaning towards canceling the screening altogether. I could not justify consuming arts from the Middle East while ignoring the reality of a genocide unfolding. When we learned that the walk-out would not conflict with our screening time, Heejoo and I decided to show a film from Palestine instead. At the time, news reports and social media were drowning in images of brutalized and dead Palestinian children. It was also the week that a video of Gazan children pleading to the world for a cease-fire came out. We settled on Juliano Mer Khamis’ Arna’s Children because we wanted to show that Israeli violence against Palestinian children did not start on October 7th, nor has it been limited to children of Gaza.

VC: Which sources did you consult when choosing these films about Palestine and how did you come across them? Could you introduce these sources and films for the readers?

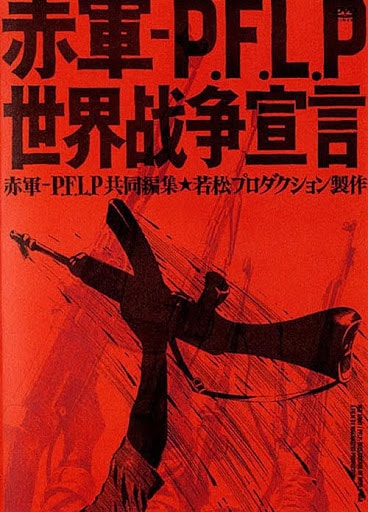

HK: I could only introduce one film and its corollaries for my lack of knowledge and methodological precision about Middle East-East Asian comparative media studies (if there is anything like that). THE RED ARMY/PFLP: DECLARATION OF WORLD WAR was directed by two radical Japanese filmmakers Adachi Masao and Wakamatsu Kōji in the 1970s. The film follows Adachi and Wakamatsu, filming the Japan Red Army Faction in Beirut and their solidarity with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). It was a pleasant surprise to find this film. Not only does it have significant status in Japanese New Wave cinema history, it is an example of transnational revolutionary solidarity between two cultures, which echoes the precise purpose of our film series. Furuhata Yuriko’s Cinema of Actuality: Japanese Avant-Garde Filmmaking in the Season of Image Politics has a chapter on Adachi and the film. It offers the historical context and the film’s artistic and political significance. There are also multiple films that give specific attention to the leader of the Japan Red Army at the time. Her name is Fusako Shigenobu. Her daughter, Mei (May) Shigenobu starred in films that deal with the legacy of female left wing revolutionaries, such as Shane O’Sullivan’s Children of the Revolution and Eric Baudelaire’s The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years without Images . Children of the Revolution was recommended by Professor Junko Yamazaki in our Department of East Asian Studies. If there is an opportunity, I would love to watch it.

XW: Currently there is a renaissance in Palestinian films, and I found the website Palestine Film Institute a huge help in tracing the evolution of Palestinian film making. I consulted Hamid Dabashi’s edited volume and online archive Dreams of a Nation, On Palestinian Cinema. I also came across Aflamuna (they are on instagram too!) which is dedicated to independent Arab filmmakers. I am especially grateful to my friend Adam Anabosi, a graduate student at Princeton, and Professor Fadi Bardawil, since both were incredibly generous and helpful in orienting me in the field of Palestinian cinema.

VC: How did people respond to the change/interruption in the program? Did this affect the turnout at all? What are your takeaways from these receptions?

HK: Of course, there was some confusion, but it turned out that much of the Princeton community responded positively to our series’ decision. New audiences came and shared their knowledge of occupied Palestine. Much emotional turbulence also occurred as we had to face what had been happening in Palestine. The experience once more reaffirms the idea that film screening is a communal experience. It can be a strand of political activism.

XW: We were so nervous on the day we announced the screening of Arna’s Children, because tension was high on campus and people were agitated. But I think our regular attendees welcomed it, and it even attracted newcomers. Arna’s Children might be one of our best attended events that semester.

VC: The film series and its subsequent reorientation prompt us to consider different functions and modalities of film-watching, such as film-watching as a pedagogical tool, as a mode of inquiry, and as an interruption. And the latter also raises the question of interruption as pedagogy. Along these lines, how might we consciously incorporate Palestine into our intellectual and everyday conversation with fellow students/scholars in your respective departments and beyond?

HK: I can only give a general answer. Emphasizing media literacy rather than ‘understanding the story’ of films might be one way to think about the role of interruption. Here, I use interruption in Walter Benjamin’s analysis of Bertolt Brecht’s epic theater. Benjamin notes that the organizational force in Brecht’s play lies in its disruption and unfamiliar change in dynamics between audiences and the stage. Rather than quickly identifying the characters’ feelings encouraged by narrative films, we could discuss why this film feels so unfamiliar and what formal, aesthetic elements make both art and political reality beyond the scope of easy understanding. For this reason, I want to focus more on discussing media literacy in future screenings. Making political issues visible and audible is an essential organizing tool. Just like our film series’ introductions to the films, we try to speak and stand in solidarity with occupied Palestine. I think that sensory exposure to the issue of concern shapes people’s perspectives.

VC: Could you tell us about your current theme?

XW: Our theme for Spring 2024 is “Drifting Bodies” where we explore various forms of diaspora, migration, and displacement. Heejoo came up with the title to highlight the different manifestations of “bodies” in dislocation.

HK: We will see more bodies drifting and migrating around and across borders. History of war, occupation, neoliberal economy, traveling, the question of identities are all combined.

Vero Chai is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Rutgers University and an editorial assistant of positions: asia critique. Her research concerns the interplay of film, literature, and photography vis-à-vis the archive, with much of the theoretical grounding in Afrofuturism and an emphasis on the Asian diasporas and their sonic, affective, and intersubjective articulations. She is also interested in critical university studies and has published “University and Its Other: On the Referent-We of Sylvia Wynter’s ‘No Humans Involved’” in diacritics: a review of contemporary criticism.

Heejoo Kim is a Ph.D. candidate in the East Asian Studies Department at Princeton University. She works on contemporary Korean and East Asian media culture after the Asian Financial Crisis. Kim’s research incorporates multifarious methodologies from interdisciplinary training. She aims to situate contemporary Korea as a critical locus in a broader ecology of knowledge and sensibility. Kim’s research interests include media and film studies, techno-aesthetics, cultural sociology, feminist and queer body and space, and dissent politics of art-urban collectives.

Xinyi Wei is a PhD candidate in the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. Her dissertation examines the social history of slavery in medieval Iran and China between the 13th and 15th centuries C.E. Drawing inspirations from subaltern studies, Black Feminism, and Afropessimism, Wei’s research considers how the exploitation of unfree female bodies participated in the construction and reproduction of human hierarchies before the advance of racial capitalism. Outside of her research, Wei is interested in using film as a tool for community organizing and pedagogy.

Critical Companion to “Re-Orienting Desire” from positions: asia critique

Earl Jackson Jr., “Desire at Cross(-Cultural) Purposes: Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” 2:1 (1994)

Martin F. Manalansan IV, “(Dis)Orienting the Body: Locating Symbolic Resistance Among Filipino Gay Men,” 2:1 (1994)

Yukiko Hanawa, “Inciting Sites of Political Interventions: Queer ‘n’ Asia,” 4:3 (1996)

Gayatri Gopinath, “Nostalgia, Desire, Diaspora: South Asian Sexualities in Motion,” 5:2 (1997)

Cui Zi’en, “The Communist International of Queer Film,” 18:2 (2010)

Petrus Liu, “Why Does Queer Theory Need China?” 18:2 (2010)

Lisa Rofel, “Queer positions, Queering Asian Studies,” 20:1 (2012)

Miyo Inoue and Aaron Kerner, “Imagining Reality as a Set of Chinese Boxes: An Interview with Matsumoto Toshio,” 22:4 (2014)

Howard Chiang, “Gender Transformations in Sinophone Taiwan,” 25:3 (2017)

Gavin Walker and Naoki Sakai, “The End of Area,” 27:1 (2019)

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.