Laurence Coderre (30 July 1984 – 8 January 2026) was our colleague, our friend, our inspiration. Born in Canada, she went to high school in Binghamton NY; her undergraduate degree is from Harvard and her PhD from Berkeley. She spent a postdoc period in Michigan before coming to NYU, where she was a tenured Associate Professor in East Asian Studies. Her book, Newborn Socialist Things (Duke 2021) immediately was hailed as a pathbreaking study of Maoist China, and it continues to make waves in the China field and beyond. Her parents, Shirley Smith and Jacques Coderre, along with the East Asian Studies Department at NYU, organized a “celebration of life” event on January 29, 2026. These four testimonials for Laurence were among the many delivered at that moving and joyous event.

S.E. Kile

For the past decade, Laurence and I have met weekly for a writing group of two. It is fitting, I suppose, that I first encountered Laurence in writing, in 2014, when I read her application to the Michigan Society of Fellows. On that first meeting, I sensed a patience, a curiosity, an openness in her approach to her objects, particularly in the way that recorded sound and the human body figured as things in the process of subject formation. What struck me even more was the way that that imagination and flair in the conception of her topic shifted, in their execution, to a methodical, bold, and very compelling working out of how those things thus refused to confirm the stories people had been telling about them. I remember thinking, then, that that voice sounded fearless. I remember thinking, I have got to meet this person. After a decade of friendship, I think I understand something of the relationship that this masterful, defiant, typo-free, and utterly unmistakable written version of Laurence held to her life off the page – that is, to a daily refusal on her part to confirm the presumptions people made about her, the assumptions they made about what her own body meant, absent the cloak of her meticulously crafted words.

As it happened, a spot in the Society of Fellows that year wasn’t in the cards, but Laurence was selected for one of the inaugural postdoctoral fellowships at Michigan’s Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies, so she ended up at Michigan that fall anyway. At the end of some academic lecture early in the fall semester, I remember chasing unceremoniously after her as she made her way to the elevator, eager to introduce myself. We got to talking, and at some point that year, Laurence suggested that we form a writing group. We met at Sava’s in Ann Arbor for a time, and shifted to that glitchiest of videoconferencing apps, Bluejeans, when she moved to New York to start her job. As we started out on the tenure track, our writing group remained fundamentally a place to think and talk about what to write, but it morphed into also being a place to think about our lives and their many competing priorities, about how to apportion time to write in the midst of new responsibilities. Writing group was also a shared identity, a pronoun even: we referred to each other in the singular and collective mostly as writing group, abbreviated WG.

I was impressed, from the beginning, with how organized a thinker Laurence was, how absent the scattered thoughts and false starts that litter my own notebooks and legal pads and hard drive were from her process — she would work through ideas in her mind to near final form before sending them on their way in elegant, finished prose. She set modest writing goals, but her 500 words or three paragraphs would come out fully formed in her inimitable style. She held on fiercely to that style, to the frustration of many a copy editor.

Already virtual, when the pandemic came, writing group felt somehow prescient. We switched to Zoom, where we found escape in the virtual beach background with animated waves. Laurence and her family had been traveling to Aruba some winters, and now that no one could travel anywhere, that shared virtual background made the Zoom room feel like a real destination. One day on that beach, I told Laurence that my editor had insisted I give up the long-planned title for my book. After some exhausted brainstorming, I had sent my editor a list of six equally awful titles, one of which she had already chosen and installed in the proofs. It was too late, I told writing group (that is, Laurence Coderre), to change anything. Over the next seven or so minutes, Laurence made clear that writing group could not live with, that I could not live with, my book being known by any of those mealy titles. She prompted me to think of a phrase from my primary sources that might encapsulate some of the arguments I was trying to make, and she approved, heartily, and with substantial relief on her face, of the first one that came to mind.

We finished our books; we got our tenure. We then both started working on new projects: reading scholarship, hunting for primary sources, trying out arguments. But the writing was slow. In October 2025, after another weekly report of getting everything done but writing, we decided we needed to put some pressure on our weekly writing goals. We came up with the “Writing Group Negative Incentive Post-Tenure Plan,” which would require us to donate $20 to a cause we found vaguely unappealing if we missed our weekly writing goals. With money on the table, Laurence finally came out with the problem that had delayed her progress on her planned second scholarly monograph. She was unable to shake the feeling, she said, that she could write nothing until she had written a memoir about her experience living with her disability.

It worked – Laurence started her memoir, and I started my monograph, and we both met our goal every week. (When Jacques found out how cheaply we could be motivated, he didn’t let us hear the end of it.)

On December 19th, Laurence’s writing goal was not numerical, but to “finish the damn preface.” Which she did.

The next week, even though we had waived the penalty for the holidays, Laurence began writing the first chapter of the memoir.

On December 26th, she sent a text: “Reporting to wg: Inspired by wg’s example, I now have a new document with 309 words. Look at us go!”

A few minutes later, another text: “Update: 423 words. I decided to keep going with a quote.”

In the final months of 2025, that is to say, Laurence began to work through, for a reading public, how it was for her to be in the world. In closing, I’d like to share those last 423 words with you:

Season 1 of Netflix’s The Witcher turns, in large part, on a choice made by a young mage, Yennifer of Vengerberg (Anya Chalotra), to remake her body at the expense of her ability to bear children. We first meet Yennifer in Episode 2, “Four Marks,” as a gnarled and abused girl who escapes a beating by accidentally performing magic. She is subsequently sold by her father to the head mistress of a sorcery academy for the dirt cheap price of four marks, less than the price of the pigs she is forced to tend and bed down with. Her humped back, serpentine spine, and crooked jaw are attributed to the poisonous contamination of elf blood. Yennifer’s remarkable magic initially stems from her rage at her forced helplessness, a helplessness rooted in the world’s revulsion at her disfigurement. She becomes fixated on a need for power and control over her own destiny. Attaining that power and control requires a drastic change in the way she looks. That is, within the context of the show, power and beauty go hand in hand. The former is predicated on the latter.

Yennifer is in luck, here, for her the end of her magical education or “ascension” to the Brotherhood of mages is accompanied by two things: “the enchantment” and an appointment as advisor to/manipulator of a royal court. The enchantment, which we later learn in Season 3 was specifically designed to help get women a seat at the Brotherhood’s table, is a one-time opportunity to completely remold one’s body from head to toe exactly as one desires. In a triumph of imagination over nature, the body becomes a medium sculpted by a magician’s hand, always with a view towards the maximization of beauty in the quest for power. Talk about a position of singular privilege. As headmistress Tissaia De Vries (MyAnna Buring) tells Yennifer in Episode 3, ”Betrayer Moon,” “There is not a person alive that does not look into the mirror and see some sort of deformity. Except for us. We remake ourselves on our terms. The world has no say in it.” As for the specifics of Yennifer’s new look, Tissaia counsels her to “[i]magine the most powerful woman in the world. Her hair, the color of her eyes, yes, but also the strength of her posture. The poise of her entire being.” She thereupon magically transfers the image in Yennifer’s mind onto the mirror. Kept hidden from the viewer, it is nonetheless meant to serve as blueprint for the transformation to come.

S.E. Kile is Associate Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Michigan

Rebecca E. Karl

What can I say about a friend I knew so well and yet so little? About a person whose expansive life exceeded every parameter I could have imagined? About someone I thought I had time to deepen a friendship with, but whose time ran out too soon, too early, too young? I miss her already so much: her wit, her intelligence, her self-knowledge, and her impatient generosity towards the abled world, in which she had to operate but which sometimes – often even? — did not recognize or yield to her needs and desires. As I was preparing for this semester’s teaching, which I would normally be doing with Laurence for a course we’ve collaborated on for over a decade on the Chinese Cultural Revolution, I have had occasion to think intensively and frequently about her. I was tempted to remember the first time we taught together, in Spring 2017, when, after the assistants in EAS set up her computer and linked it to the classroom tech, I nevertheless busied myself about the classroom pretending to know what she needed and what I could do. Several weeks in, I finally saw I had no idea how to help and I asked her what she needed me to do. Laurence quipped: “It is always a source of amusement to see how long it takes able-bodied people to admit they have no idea how to handle themselves around me; you’re no better than average: it took you a few weeks.” That’s when I knew for sure that we’d not only be co-teachers, but we’d be friends and allies in the institution, in the field, in our lives.

I wanted to say a bit about Laurence as a teacher and advisor, in the classroom and with her graduate students. I’ve taught at the undergraduate level with Laurence a lot, and I learned consistently from her stern but sympathetic mode of interaction with students. While I tend towards the overtly gruff; she tended towards the playfully strict. She treated students with great respect and a certain wry humor, and they would sometimes develop a misconception and think that they could get the better of her; were they ever mistaken! She had a steel spine and a steel will, well disguised by the wheelchair and her easy demeanor. Sitting in her classroom, witnessing her unspool an analysis was a real privilege: it modeled for students (and for me) how to approach learning, and how to appreciate the act of thinking itself. Since her passing, I have heard from a number of the students we co-taught in years past, many of whom write of how much they loved learning from her, how much they appreciated her generosity and erudition, and how much she impacted their sense of possibility and accomplishment.

I also have co-advised graduate students with Laurence, and it is in this setting that her brilliance shined so brightly while her patience was sometimes tried so fully. Her probing questions based in her close readings indicated how seriously she took the task of instruction and how much she valued intelligent students who challenged and pushed us to be better. By the same token, I marveled at how patient she could be with students: her intellectual commitments to them and her persistence in encouraging them to live up to their potential are enduring lessons in what it means to be an educator and a mentor.

Of course, Laurence’s writing, her research, and her publications will stand as enduring legacies to the largeness of her mind and the range of her capacities. In the near future we will be holding some workshops devoted to exploring her work and her intellectual legacy more fully. For starters, at this year’s AAS (Association for Asian Studies), I along with Emily Wilcox (who worked with her at Michigan) and Andrew Jones (who was her advisor at Berkeley) will host a special session on Laurence and her work. Those of you intending to be at Vancouver, please do plan to join us at the Convention Center, West Meeting Room 201, on Saturday March 14 at 12:15-1:45pm.

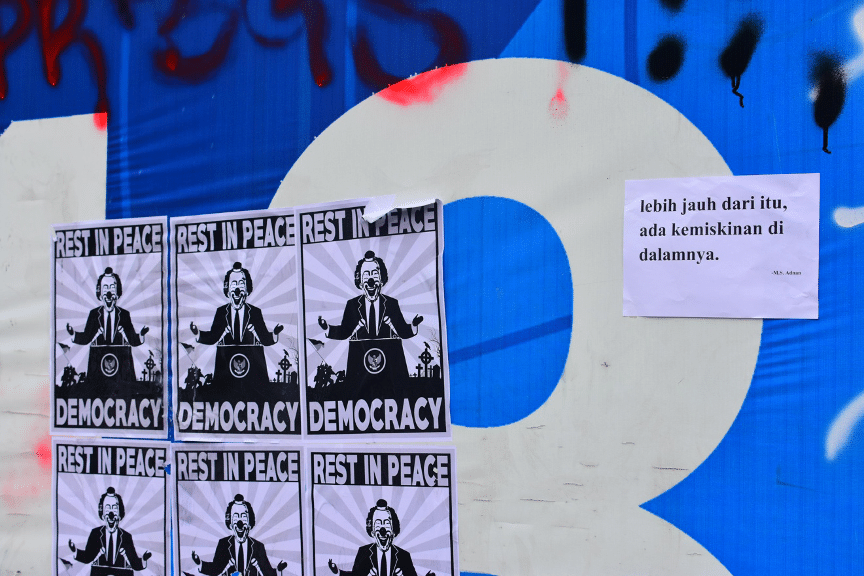

I’ll end on a small anecdote. In the first year we co-taught our Cultural Revolution class – in Spring 2017 – we had a group of perhaps 24 students. We started each class with an image from the CR, to try to help students build a vocabulary and capacity for “seeing” what was the visual landscape of social life at the time. About three weeks in, one of the students commented that they noticed that many of the posters we asked them to look at focused on torsos and hands. Laurence deadpanned: “I’ve always thought legs were overrated.” I guffawed while the students looked around in panic, until Laurence made it clear they could laugh. Of course, I cannot know what living in her body was like for her, and I know that she had started writing explicitly about her relation to her disability. What I also know is that she inspired me with her courage and her intellect, and, most of all, I know how I will miss her so.

Rebecca Karl is Professor of History at NYU

Todd Foley

We all know what an outstanding scholar Laurence was, and many people at NYU got to know her as a gifted teacher and caring mentor. For my part, I’m not really best positioned to speak to the special ways she fulfilled these roles, although she was sometimes a teacher and mentor to me, and we did sometimes talk about scholarship – or “the content,” as we called it. But to me, Laurence was mainly a good friend. She was my regular drinking buddy, and, as she called me in her acknowledgements, a “partner in crime.” I’m finding it hard to describe something so feelings-based and ineffable as a good, true friendship. But maybe our criminal activity is one place to start: we had such a good time sharing our unvarnished opinions, exchanging our not always laudatory observations on academia, and sneaking a Guinness before class (although to be honest that was usually just me). I loved dropping by her office, and seeing her give a wry smile and say “shut the door,” which was always a prelude to some entertaining remarks.

I first met Laurence almost exactly ten years ago, at the ACLA at Harvard. At one point a friend of mine asked me if I knew her, as she had just gotten the tenure-track job at NYU. That was news to me, and I have to admit, given her no-nonsense seminar performance, I was a little worried—this person means serious business, I thought, and I was not anticipating a new friend. But as soon as I talked to her on one of the breaks, I knew I was wrong. I think we could both tell right away that we were signing off the same hymn sheet, so to speak, and I remember us tittering together right up until the final dinner.

That was one of the great things about Laurence–she often did mean serious business, but she was also fun. I think part of the reason for this was her impeccable judgment–she knew what was funny, or what I’d think would be funny, at the right times, but she was also a solid rock of professionalism who never compromised her intellectual rigor. I recall meeting with a prospective graduate student a few years ago who was wondering about the graduate program’s structure and professional outcomes–don’t worry, I said, we have Laurence. It might have been a weirdly ambiguous answer, but that’s how I thought of her: totally dependable, able to steer any ship in any weather. I called her “laoshi,” like she was one of my college Chinese language teachers–it was a joke, but also an expression of the real awe and respect I had for her.

Laurence was genuinely caring and thoughtful. At the end of the semester she’d present me with Scotch eggs to eat on the train, a nod to my favorite snack at one of our regular hangout spots. For a while she’d also give me bags of Sixlets for my son Cliff, until I sheepishly had to reveal he didn’t really like them anymore and I’d just been eating them myself. Before the pandemic, my dad and father-in-law teamed up to build a ramp so she could get into our house in New Haven. She used it once, and we had a great time. I’d always assumed we’d be using it again, but the circumstances never allowed it. I’m so honored to have gotten to know Laurence, and I’m going to miss her very much.

Todd Foley is Adjunct Assistant Professor in East Asian Studies at NYU

Christine Ho

I first met Laurence at a conference in Ann Arbor. She wheeled her way toward me and said, “Why haven’t I met you before?” Thus, I was lucky enough to have been befriended by Laurence.

Over the next few years, no conference on socialist culture was complete without Laurence and her mom Shirley, the indefatigable travelers. Many greater minds than mine have attested to Laurence’s tremendous standing as an intellectual, teacher, mentor, colleague. Certainly her approval—and actually Shirley’s approval, too—was very important to me. But what I really loved about Laurence was how she was so unrelentingly pugnacious and, above all, deeply stylish. When I think back to my memories of Laurence, I remember her sparring with coolheaded tenacity with an esteemed historian of Chinese consumption, refusing to give an inch; I think of her assuring her dad at the National Gallery that I was not going to yap on about color; I think of her going back and forth in front of The Ambassadors looking at its anamorphic skull and saying drily, “Cool trick”; I think of her telling stories about viciously bargaining over porcelain sculpture in Jingdezhen; I think of her airy office, the only scholar’s office I have ever seen where the books were beautifully arranged around works of art placed on stands.

Above all, I remember the talk on Zoom she gave at Berkeley during the late pandemic. At the end, Laurence appended some advice to the gathered graduate students, jittery with tension as they waited to give their own papers. She described her own writing blocks and occasional doubts, and talked about how she got herself out of the valleys of academic work. Then she concluded with– “At the end of the day, everything’s work.” Then she repeated herself: “It’s all work.” At the time, as a new parent, I felt both seen and also completely exhausted by this advice. But now I understand it as she intended it, that all experiences high and low mattered and enriched. From video games to bubble teas to music to vampire shows to reading, and everything else that Laurence took pleasure in, all informed each other, and were inseparable from a life of thinking about being human. And this was perhaps what we all loved about Laurence, that she was so deeply humane.

I did not know you well, Laurence. There were aspects of your life and work that I could only partially glimpse. But I thank you for asking us to go back to work.

Christine Ho is Associate Professor of East Asian Art, UMass-Amherst