Bishnupriya Ghosh examines the “frontline intelligence” of healthcare workers who recorded or reported their qualitative perceptions during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

edited by Lan Li

Over the last year, the COVID-19 catastrophe has taught us many a bitter lesson. One of the most difficult ones is the steady corrosion of social trust that dogged public health efforts across global regions, perhaps most notably in large democracies headed by populist authoritarian strongmen such as Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, and Jair Bolsanaro. It will take years for the dust to settle on comparative studies. This is a but modest attempt at understanding one dimension of the problem that stretches beyond the COVID-19 episodes: the problem of collective intelligence that ensures public buy-in for health measures. Field notes from the epidemic frontlines—or “frontline intelligence,” as I characterize it—can foster a concrete sense of a novel condition, moving us beyond anodyne public health messaging. Frontline healthcare workers recording qualitative perceptions lead the way, even as they inhabit precariously unsafe conditions.[1] Perhaps closer attention to such first looks can facilitate public immersion in epidemic conditions by rendering statistical abstractions as sensuous information.

This is more and more possible because of ever-widening global telecommunications infrastructures and corresponding media devices (cellphones to tablets), media platforms (wikis to WhatsApp), and media cultures (micro-blogging to video-sharing). If COVID-19 is the first “digital pandemic,”[2] what can we learn from “frontline intelligence”? What can it teach “us,” the wider public, about pandemics to come? How might the dispersive and sensuous qualities of field notes emplace publics distrustful of state advisories at distributed points of care and make survival a collective enterprise? Might frontline healthcare workers, often seen as part of the greater swarm, the foot soldiers rather than the decision-makers, be the best knowledge-makers in bringing the pandemic home? Conduits of social trust, healthcare workers are uniquely placed to accomplish such a task. I look at two coteries of frontline healthcare workers to explore the epidemic intelligence of their first looks: registered nurses (RNs) working in COVID-19 wards in the United States, and social health workers who gather data door-to-door in India. I place them in relation to each other to draw out commonalities of epidemic intelligence at the frontlines, despite glaring discrepancies between them in terms of resource distribution, clinical expertise, and the public health systems that employ them.

Pandemic archives since the late nineteenth century have left traces of frontline healthcare worker testimonies scattered across institutional platforms.[3] Media affordances since the late twentieth century in resource-rich contexts have made it possible for frontline healthcare workers to record their qualitative perceptions, sometimes as the historical record (as in the National Institutes for Health’s “In Their Own Words” archive for HIV/AIDS), and, at others, as urgent public health messaging (as in the COVID-19 episodes). For frontline healthcare workers without such access, global communications infrastructures are expansive enough to offer media platforms that range from WhatsApp videos to worker monthlies to structured interviews in news media. The American Journal of Nursing (AJN)—the leading publication for the profession in the US—hosts the “Off the Charts” blog with a dedicated “COVID-19 (*regularly updated*)” site[4] and a rapid-fire “Frontline Nurses WikiWisdom Forum”[5] for RNs to share information. Frontline observations also find audiovisual documentation across platforms: these documents range from films such as Carolyn Jones’ In Case of Emergency (2020) and the New York Times Death, Through A Nurse’s Eyes (2020) in the US, and the NewsMinute Day in the Life (2020) in India.

India’s 1 million Accredited Social Health Activists (or ASHA workers) who collect health data for the National Health Mission have recourse to a monthly periodical in some states and share information on Whatsapp; but there are no institutional archives for their first looks.[7] Indeed, their views from the field made landfall across news channels because of the precarity of their COVID-19 frontline encounters. Highly local, embedded in their communities, ASHA workers are known for handling maternal and newborn care in rural, peri-urban, and urban areas. When COVID-19 broke out, they were deployed for door-to-door data-gathering, contact-tracing, and health assessments—all for a bonus of Rs.1000 a month ($13.50) that failed to arrive in 75% of the states.[8] As independent media channels such as Wire.in or local news channels and feminist digital platforms (such as Behen Box[9]) documented their stories, a clearer sense of the difficulties of testing, quarantining, and social distancing emerged, calibrating differentiated pandemic experiences.[10]

The point is not to only celebrate RNs and ASHAs as the proverbial “unsung heroes.”[11] This is done across the mainstream media archives, microblogging sites, and activist media networks, and rightly so. Nor is it to point out the shoddy, sometimes deadly circumstances that confronted them in the contact zone of the epidemic (lack of PPE, long shifts, public fears, scant knowledge). Both are important moves for recognizing how “we” extract value from frontline workers, appreciating their supportive care as supplements to real changes that we ascribe to institutional policies and scientific research. Beyond this extractive valuation, we might ask what fragmented “field notes” can induce in listeners/readers/ viewers removed from imminent danger. Below I chart three dimensions of first looks to track how frontline intelligence re-routes qualitative perceptions of a global pandemic “out there” (in the news as abstract data) to the “in here” (in bodies, homes, neighborhoods) of lived experience.

As multi-leveled emergences, pandemics mandate the habitation of different orders of association—medical and social, economic and technological. Global publics struggle to keep abreast of emergent medical insights and therapeutic/prophylactic advances as well as job losses, evictions, drying revenue streams, mental health, and social isolation. The very dispersiveness of frontline intelligence is invaluable in this regard. In RNs and ASHA observations, the medical state is always singular, taking into account the convergence of factors (patient histories to family situations) enfolded in one instance—effectively personalizing a compound experience.

Noting the face-off between “business” and “health” concerns in the U.S., four RNs working in New York City hospitals recognize widely divergent pandemic experiences to be the main problem. “When they look around, everything else looks normal,” they write. “In many areas of the country, they may not even know anyone who has gotten sick, let alone died. Their hospitals are still quiet. For them, the obvious threat is not illness, it’s poverty. The loss is not of a friend or father or son, it’s of their livelihood, their ability to care for their families. They fear they will never recover. We understand. Though we are all confronted by the same threat— COVID-19—our experience of it differs dramatically. We as nurses are immersed in the human suffering of the illness itself, while many others are immersed in the human suffering of the economic and social fallout.”[12] Holding onto socioeconomic differentials and pandemic multidimensions, they make the case that the critical zone maybe just around the corner for those still-immured from harm. In the Indian case, health advisories were difficult to deliver across the socioeconomic spectrum, often because of crowded living quarters and endemic labor migrancies. This is why ASHA workers faced attacks from some families fearful of prohibitions for work and travel should any member test positive for COVID-19.[13] One ASHA working in the northern state of Haryana noted fears further arose from erroneous and scant information: “People are scared of this disease. Many think it spreads through touch. They keep saying ‘social distancing’ in the media. Even after I explain what coronavirus is and how they need to stay apart, I don’t know how to look them in the eye. What is social distancing in a 10-foot by 10-foot house where seven people live together?”[14] Here is a candid assessment of living conditions that make following standard health prescriptions difficult to follow; here is the effortless inter-leaving of medical and the socioeconomic conditions. The fullness of singular situations in the frontline optics reveals the very entanglements that sometimes underlie resistance to health policies.

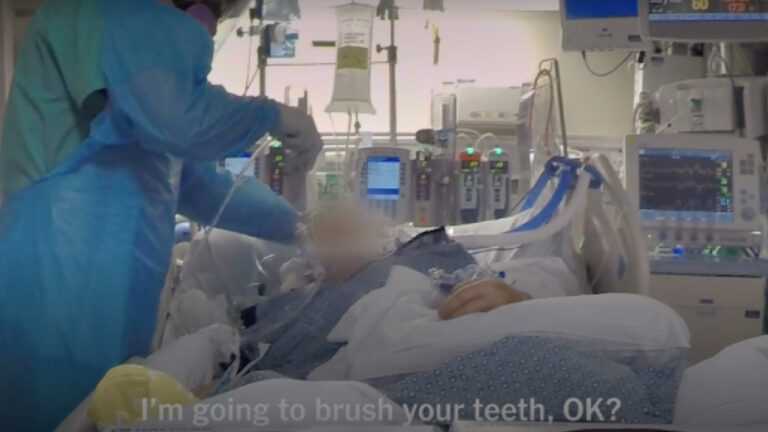

Public trust turns out to be a heavy burden for both RNs and ASHA workers. Both coteries espouse clear commitments to the communities that rely on them. The RNs in emergency wards are often the last link between families and loved ones who die alone: “We see the suffering, the loss, the final goodbyes taking place over FaceTime, the sadness of dying alone in a makeshift room in a temporary ICU.”[15] RNs across the US speak of heartbreak and despair in operating existentially, as the last link to the human world. In cellphones and tablets, they become the interface between patients, friends, and families, habitually exposing the medial dimensions of the pandemic experience (see Fig.4). Balancing the heavy demands—long shifts, proverbial uncertainty, emergent advisories, and emotional drain—some nurses are outspoken about the sacrificial demand. As contributing editor to AJN Theresa Brown remarks: “All nurses know that saying, “A nurse is a nurse is a nurse.” It encapsulates the idea that all nurses are interchangeable and therefore don’t need to be cared for as employees. Covid nurses profoundly felt this lack of caring, to the point that many of them quit their jobs, if not nursing altogether.”[16]

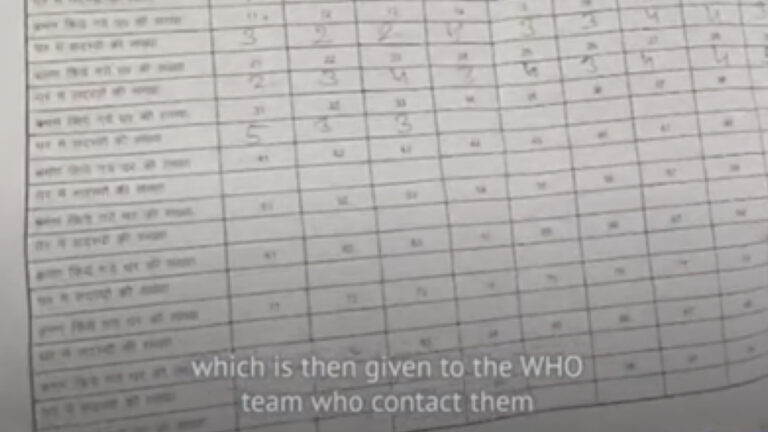

For the ASHA workers, community investments fuel their work. Experienced ASHAs are an established social network, connecting households to state public health infrastructure. During the COVID-19, they linked remote rural areas to both the National Health Mission and the World Health Organization (WHO) data collection enterprises (Fig.6). But beyond administration, ASHAs are hyper-aware of their embeddedness in the communities that they serve: “The community trusts and respects me,” says Minara Begum from Assam’s eastern district. That’s the only reason why I stay on.”[17] Faced with sudden distrust, many feel undervalued for their disproportionate share of the COVID-19 burden—the twelve-hour shifts, the trek on foot in the summer heat (armed with salt, lemon, sugar, and water), the uncertainty of their reception. Several ASHA Unions have WhatsApp groups as support systems, and these sustain the ASHAs in their role as the social network. In one notable instance, faced with the lack of PPE, an ASHA from the Haryana Union made a video of turning her chunni (headcover) into a protective shield for the face.[18] That the video went viral among ASHAs revealed the subterranean mobile network among the workers separated by linguistic differences and regional eccentricities.

The social and technological networks exposed in following RN and ASHA frontline notes establish the relationalities constitutive of epidemics: the many interfaces between individual and population, clinical procedures and public health, state and global institutions. One gains an inside look at the complex lumbering machinery of infectious disease management without the abstraction of institution-speak. Epidemiologically, audiovisual documents on RNs and ASHAs spatially emplace the wider public within nested disease milieus. Nurses wearing cameras show us the entanglement of bodies and machines in the ICU as the RNs negotiate a jumble of beds, screens, laptops, wires, tubes, gloves, gowns, liquids and pills. We come to inhabit an intricate assemblage. The ASHA treks take us into neighborhoods and enclaves not just marked administratively (usually in a subtitle) but also physically: the small lanes and pathways, courtyards and squares, an intimate encounter with disease spread that obviates epidemiological cartographies.

In both cases, the lack of PPE placed the RNs and ASHAs in jeopardy. In the frontline notes, this observation arises frequently, voiced in despair and anger. The precarity of frontline proximities resonates as distress, underscoring the pandemic as a deeply somatic experience. The RNs habitually balance necessary protections with the need to humanize: “Some of us pin a picture of ourselves to our gown so patients can have a connection to a real person, not just the muted voice of a faceless clinician behind a mask, covered head to toe in personal protective equipment.”[19] The long hours nurses spend with patients establish an intimacy absent in the physician’s visit. The ASHAs drive home this embodied connection in no uncertain terms: “A doctor’s job begins only after we have monitored every person in our community and identified people with symptoms,” said Lakshmi Singh, an ASHA in Bhind, Madhya Pradesh. “Yet, when the doctors come into the village they are in full gear, looking like robots, while we are not even given a mask.”[20] While Singh’s point concerns the precarity imposed on the ASHAs, it is also a recognition of the physical immersion of the workers within the communities that they serve. The ASHAs speak of individual symptoms and living situations, of water and temperatures, of fears and desires, conveying a concrete compound experience of facing disease emergence. RNs who volunteered during COVID-19 to serve communities present similarly sensuous emplacements. One RN who signed up for the California Health Corps in Pasadena recalls the shock of overwhelmed assisted living facilities: “I saw soggy diapers on the floor at the heads of many beds on most mornings. One day a bedbound patient needed the bedpan. I searched every closet and drawer but there were no supplies. I filled a basin with warm water and cut up a PPE gown to make washcloths to clean the patient.”[21] The epidemic sensorium emerges bringing publics closer to suffering bodies, to endemic scarcities, to the onerous work of embodied care. In this regard, first looks flesh the statistic.

Historically born of war, epidemic intelligence was the brainchild of Alexander Langmuir, an epidemiologist in the U.S. Army 1942-46 largely responsible for establishing the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the CDC in 1951 which was a precursor to the WHO’s Epidemiological Surveillance Unit. As such it was as a highly-specialized form of expertise with restricted circulation, one which has undergone increasing datafication in the last forty years. This post-World War II model of “epidemic intelligence” as expert espionage against germs lives on as field specialists gather data for global infectious disease detection and control; as we have seen, they are the necessary supplement to a formidable armature of contemporary real-time disease surveillance networks (DSN).[22] But in this essay, frontline intelligence suggests something else. In the stories of RNs and ASHAs, another modality appears: a distributed swarm intelligence, dispersive and sensuous, that can connect wider publics to suffering bodies, remote dwellings, and affected communities. This, too, is epidemic intelligence in collective vein. As qualitative perceptions spill over in fragments and traces, pulling us into the eye of the storm, the pandemic becomes lived experience. Their first looks emplace us in the field. Perhaps such participatory inhabitation can turn attempts to stem pandemic injuries and losses into a collective enterprise.

Bishnupriya Ghosh teaches in the Departments of Global Studies and English at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is completing a monograph entitled The Virus Touch: Theorizing Epidemic Media which explores how mediatic processes detect and compose epidemics as crises events. In the COVID-19 interregnum, they found a sudden interface in their research trajectories: hence, the imperative to share first looks that reflect upon the COVID-19 pandemic.

Music by MOIZ