By now, an impulse to document, archive and process traces of our life has become a widely shared phenomenon across the world in the time of COVID-19. A plethora of coronavirus diaries and quarantine vlogs are circulating online, an increasing amount of web users are consciously saving screenshots of valuable information and building personal archives, hundreds of documentation projects are flourishing and calling for participation, and a string of academic and art journals are collecting think pieces to register markers of our thinking and contour the crises of our time (as what we are doing in this issue). Although it might still be too early to call this boom of coronavirus archives a “documentation movement,” what we are observing now is an ongoing process of collectively building a participatory digital archive about our life in the pandemic. This rapidly accumulating archive involves not only the organized efforts from professional “chroniclers,” such as oral historians, archivists, journalists, writers, translators, filmmakers, artists and academics, but also the creative and structureless uses of social media employed by amateurs in a guerrilla fashion. Instead of focusing my analysis on a particular form of archive, my goal here is to think broadly on the impulse behind these numerous practices of documentation: why are many of us obsessed with preserving records in this pandemic? What are we driven by? What structural and temporal tensions are revealed in our engagement with documentation? What possibilities of cohabitation do our coronavirus archives open up?

To address these questions, I will formulate my thoughts in four theses. I would like to specify my entry point to the issue of “documentary impulse,” which originates from one of the major fields I study, Chinese urban cinema. In the context of Chinese cinema, the term is used to accentuate the cinematic efforts to construct a visual record of urban demolitions and unearth the traumas triggered by the collapse of home and habitats. In this essay, while I extrapolate the notion of documentary impulse from cinematic intervention to the broader practice of online documentation, what I consider crucial in the term’s valence to our COVID-19 situation is a psychic condition this term captures in a quagmire of crumbling realities and uncertain futures: the documentary impulse hits us when we find ourselves no longer at home in the realities we used to be familiar with; it is the vast gap between the past and the destabilized “new normal” that produces an urgent desire to comprehend that gap and negotiate with the political realities through documentation. In this light, the documentary impulse, echoing Jacques Derrida’s phrasing “archive fever,” is not only a desire to participate in the unmaking of a violent reality, but also a pathological condition reflective of an impasse of getting there. In exposing the tension between the dystopian reality and the constructed archive, the documentary impulse is at once a symptom of and a response to the social illness.

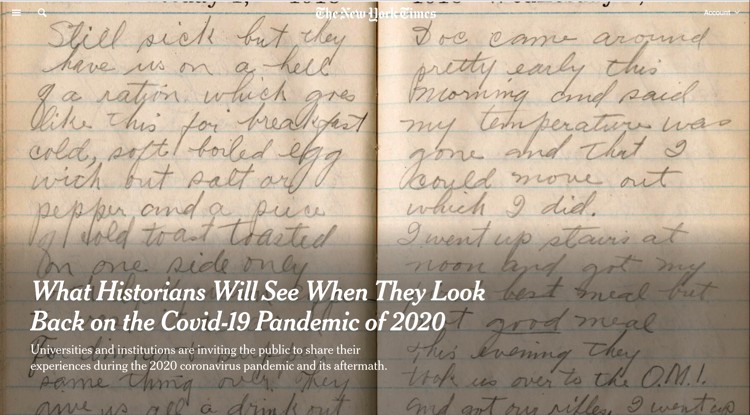

Reading the connection between the documentary impulse and the social illness, accordingly, leads to my first thesis about documentation in the time of crisis: a plethora of self-fashioned digital archives have emerged out of this pandemic when official records and mainstream media have fallen short of speaking to the nuance of everyday lived experience. The premise behind this thesis is that what we are experiencing as a pandemic today is never simply a public health failure, but an interlock of political, economic, media and mental health crises that coordinate with the spread of the virus. Under this circumstance, where a strong documentary impulse erupts is where the lived experience of numerous ordinary lives, in forms such as pandemic humor, care and solidarity, is betrayed and threatened by the current social structure, whether it be a capitalistic structure that deems millions of the economically disadvantaged “essential but disposable,” or a media apparatus that spreads pervasive misinformation, partisan biases and xenophobic hatred. When our current language is still inadequate to capture the fears and uncertainties of living in this form of political injustice, to jot down traces of the present is not only a makeshift to process the gap between everyday experience, official discourse and media representation, but also an effort to reconstruct a lexicon from the everyday and of the everyday.

A sense of the illegibility of the lived experience in the present leads to my next thesis about a futuristic imagination associated with the documentary impulse: in a time in which political violence and mis/non-representation betray our lived experience, the practice of documentation is essentially oriented towards the future, towards a promise of remembrance and justice rooted in the future. When we browse numerous collections of coronavirus archives and diaries, it is not uncommon to discover a future-oriented consciousness in examples such as “historians of the future will want to know…” and “this archive provides records for the future generation to…” In a recent rewrite of Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, Philosophy and History students Benjamin Davis and Jonathan Catlin even put down the following words as one of their “Theses for Theory in a Time of Crisis,” consolidating the link between the small stories we tell today and the archive of the future they open up:

Share small stories, and tell your own. There is more to a crisis than the headlines. Possibilities for alternative futures are hidden in the granularities of day-to-day life. Cuba’s medical brigade to Italy belies nationalist border-building as effective policy; Fang Fang’s diaries exemplify the need to keep unofficial records. The preservation of social scenes in memory is the archive of and for the future.

While documentation focuses on the dynamic act of collecting records, the archive is a space that houses the records and invites the future to enter a conversation. As Davis and Catlin formulate here, the coronavirus archive, co-created by a multitude of “small stories,” is becoming an archive “of and for the future,” because “possibilities for alternative futures” stem from the ways in which plural forms and meanings of day-to-day life are documented, presented and passed on. In forging a bond between the present and the future, the practice of documentation creates a concrete passage for the future generations to access our COVID-19 memory, relate to our current conditions of existence and be able to anatomize the political impasses that are not yet fully legible to us at this epoch. Just as Derrida writes, “The question of the archive is not, we repeat, a question of the past. […] It is a question of the future, the question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow.”

At this point, I should make it clear that an archive becomes an archive not simply because it preserves factual and historical values of the present, but probably more importantly, because it contains an imaginative and relational quality that enables the documented present to be readable, relatable and translatable to the future. In this regard, what I would like to suggest about the cultural significance of documentation is its open-endedness to a radical imagination of the future, for the future and with the future: by always anticipating an interlocutor from the future who will have salvaged the archive from oblivion and inherited the commitment of the present, the archive is kept “live” (renewable, updatable real-time) and “alive” (relatable, memorable over time) across generations.

In bringing forth the imaginative and relational quality of the archive, what I would like to consider for my third thesis is to situate the COVID-19 crisis within a larger collection of disaster archives and reflect on conditions of relationality today. How do we see this pandemic crisis not merely as a memory for the future, but also as a “future” loaded with catastrophic memories from the past? Here, different from a common grouping of epidemics that compares COVID-19 with SARS, H1N1 and Ebola, what foregrounds the basis of my cultural comparison is a catastrophic experience entailing the collapse of home, community and a normal social order triggered by an emergent disaster coupled with ingrained structural crises. This catastrophic thinking, provoked by COVID-19, leads my attention to a different set of historical experiences in the digital age: the Fukushima triple disaster, the Haiti earthquake, urban demolitions in China, Hurricane Katrina, and the September 11 attacks, etc., all of which had to deal with the same set of questions about how to reconstruct an inhabitable world upon crumbling realities, how to reform the political structures in and after the times of crisis, and how digital, visual and oral documentation could take an interventional role in these processes. The existence of these traumatic experiences reminds us that what we are living as “the end of the world” today is nothing unprecedented even to recent history. Especially in the post-3/11 Japan, conditions of economic crisis, political collusion, pervasive fear, strengthened media control, disposability of the bottom-rung and the rise of xenophobia and ultra-rightism that accompanied the Fukushima triple disaster are highly similar to a series of challenges we are facing in the pandemic crisis today. However, despite these similarities of catastrophic experiences, crises prior to COVID-19 were often confined within provincial, national and linguistic borders, in which case local and national grief and pains were often insulated from the rest of the world. Ironically, as COVID-19 is becoming a truly global pandemic and global crisis today, almost everywhere in the world is now forced to be dislodged from a bystander’s safe spot and encounter the dire realities of intensified nationalisms, border closures, exploitative capitalisms and ideological divides. With no more escape, we have to face these problems candidly and collectively.

When historians of the future comb through our coronavirus archives, “crisis,” “conflict” and “contention” will probably leave some indelible traces in their reading of our time. It is important to remember that what will sediment into our dense archives are not only gentle voices calling for solidarity and mutual aid, but also highly contentious debates and verbal attacks provoking us to rethink the ground of dialogue and cohabitation. Or let’s say, in this disturbing time in which we are all immiserated by the pandemic crisis, can we still think of cohabitation? Cohabitation not in the sense of harmony within a closed boundary of community, but, rather, in the sense of sharing the same habitat (Earth) with those who are radically different from us and understanding the stakes of intimate hatred, dissension and indifference in our living-together. In the early 2010s, Judith Butler picked up this topic of cohabitation in her reading of the Israel/Palestine conflict, by emphasizing our ethical obligations to the geographically distant Other in a world in which we cannot choose with whom to cohabit. If Butler, back then, was inviting us to imagine the distant Other as our fellow neighbor in a globally connected world, in today’s context of exploitative capitalisms and xenophobic nationalisms we will have to modify our thesis about cohabitation: rather than being someone who resides remotely from us, the Other, today, is more likely to be someone who is intimately dwelling in the same domestic or international political system with us, but being disposable in the invisible corners of the political economy, or being blamable as the suspected enemy at the other end of an ideological spectrum. This is not to say the Other is no longer our neighbor on Earth, but now we have to understand how our neighbor—no matter how close or how far this person is geopolitically from us—may be speaking and living in plural languages foreign to us and demanding a close, hermeneutical engagement of listening and translation more than ever. In other words, in a time in which we could no longer presume a fictive proximity with the Other, the strong divides of opinions across the world today are reminders of the Other’s irreducible difference that cannot be easily assimilated into one political agenda—whether it be multiculturalism or unilateralism. Such divides, I would like to suggest, are demanding us not to turn away from each other, but to take one step further to listen for the foreignness in the Other’s language, truly understand where the Other comes from, and let the foreign tongues challenge the monolingual presumptions of the world. At the risk—or, with the necessity—of sounding untimely, this effort of listening to the Other and engaging in the Other’s language is not only a precondition for working through the deep levels of distrust and violence in our cohabitation today, but also an imperative move towards possibilities of alternative ethical futures.

Having discussed the questions of futurity and cohabitation, my fourth and final thesis concerns an imagination of being with the dead and carrying their pains with us as we muddle into the future. In this pandemic in which too many families are left with no time to bid farewell before their loved ones pass away, death is only the starting point of an endlessly long process—for the ones still alive—to cope with trauma and live in pain. Just as thousands of Wuhan residents were lining up to receive the cremated ashes of their family members after the city lifted its weeks-long lockdown, grief may be delayed and unheard, but it is not absent. Just as a myriad of Chinese people continue to visit the deceased whistle-blower doctor Li Wenliang’s Weibo account and mourn the doctor every day like treating an old friend, grief and mourning, through the participatory digital archive, can take interactive, modest and ordinary means to keep alive an intimate relationship with the dead. In this latter context, the digital archive, as a “tree hole” for whispering secrets and affectionate messages to the dead, transforms into a communicative space for remembrance and community healing. Through this collective work of mourning, not only does the deceased gain a social afterlife in both the cyberscape and the memoryscape, but the ones alive are also granted a connective memory to share grief and pursue a form of delayed justice in carrying the dead together. As time goes by, even if we will gradually adjust to a new normal life and public discussions of the deceased and the pandemic will slowly die down, the existence of such a living archive will not only attest to the scars lasting into our memory, but also remind us that we are never free from our responsibility for the dead.

After all, we are all living in the shadow of history, and carrying the heavy baggage of life passed down to us.