Introduction1

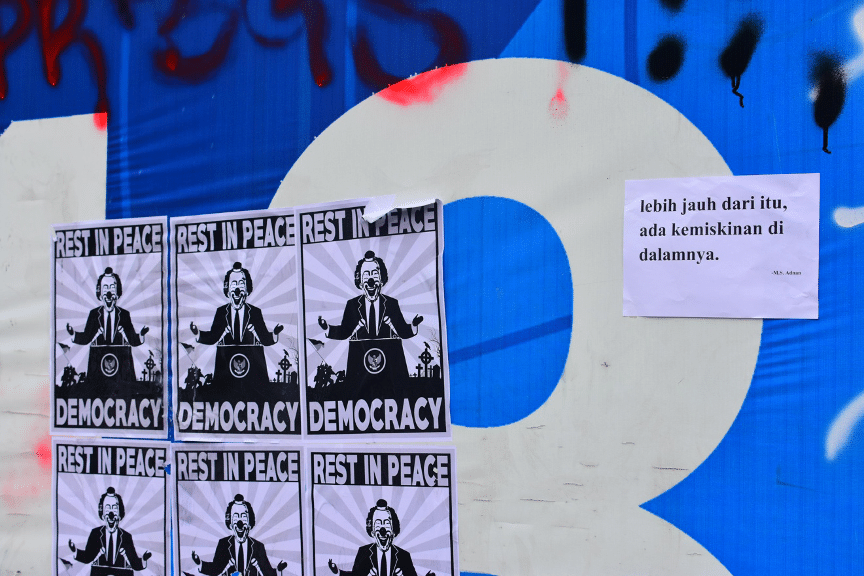

In August 2025, a dramatic wave of demonstrations swept multiple cities in Indonesia. Originating in Jakarta and its surrounding areas, it quickly spread to dozens of other cities across the archipelago. Throughout the month, social media was flooded with visuals of groups that rarely mobilized together; from university students in colored alma mater jackets, ride-hailing motorbike drivers, and mothers donning hijabs, clutching brooms and Indonesian flags. They joined forces in response to announcements made two weeks earlier about a housing allowance amounting to IDR 50 million (approximately USD 3,000) per month that members of parliament were set to receive. This figure is close to ten times Jakarta’s minimum wage of IDR 5.4 million (USD 320). The announcement came out at a time when people were questioning the government’s ability to create secure jobs and deliver basic services.

This commentary situates the late August 2025 grassroots mobilization as a continuation of a series of protests that erupted against democratic de-legitimacy and the deepening of inequalities in the past decades. We argue that as a whole, this series of protests represent a momentary coherent articulation of grassroot grievances where scattered, specific discontents among diverse groups were aligned through collective expressions that provided a shared framework for understanding systemic problems. Yet, as we will show, these articulations ‘from below’ have repeatedly been re-articulated by competing oligarchic factions to advance their own interests through strategies of co-optation, symbolic concessions, and the re-appropriation of movement languages that ended up fracturing the coherence of emerging cross-class coalitions.

We reflect on this recurring pattern of articulation and re-articulation, during which political expressions of solidarity organically form and reach temporary coherence only to be swiftly rearticulated. Rather than consolidating into a productive force capable of sustaining opposition to the hegemonic social order, each wave of protest becomes a fleeting moment of cross-class alignment of short-term interests with little capacity to coalesce and give expression to long-term politics.

We situate this pattern of articulation and re-articulation within the main contradictions of Indonesia’s democracy, where democratization (1998 to 2024) has shaped competitive political terrains while leaving intact the oligarchic social formation consolidated under thirty decades of authoritarianism (1965-1998). Factions within this social formation struggle to concentrate wealth and power within their respective networks, all the while neutralizing oppositional forces. Meanwhile, grassroots grievances are expressed in disjointed ways, shaped by historically constituted processes that inform organizations’ identities, interests, and capacities as well as the divergent ways political subjects understand their own specific struggles. Within these contradictions, articulations of grievances are often re-articulated in ways that benefit the interests of competing elite projects rather than the interests of broad-based counter-hegemonic forces.

Oligarchic Democracy and Inequality

We situate the series of protests that took place in the past decades as a response to the democracy setback in Indonesia. The democracy setback was accompanied by the formation of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s (2014-2024) political dynasty. It paved the way for the victory of authoritarian President Suharto’s former son-in-law Prabowo Subianto and Jokowi’s son Gibran Rakamuning in the 2024 Presidential Elections, which arguably marks the end of democratization. These processes transformed and entrenched the oligarchic social formation within a political economic system where competitive elections take place and electoral institutions exist.

These transformations intersect with local conditions of uneven development that have fostered the rise of populist leaders in the past decades. This can be seen in the likes of Ridwan Kamil (Bandung, West Java), whose persona was built around being a people-oriented technocrat; as well as Tri Rismaharini (Surabaya, East Java), who is known as a motherly defender of the poor against bureaucratic inertia. But none rose as influentially as Jokowi, “the man of the people,” during his tenure as mayor of Solo, Central Java in 2005, continuing through his victory in the Jakarta gubernatorial elections in 2012, and culminating in his Presidency in 2014. In his final term, this ”man of the people” persona accompanied his extensive infrastructure development and welfare distribution programs. These programs masked his government’s reliance on bond-financed growth that funneled debt through state-owned banks to underperforming state-owned enterprises.

Populist policies and programs have served as vehicles through which meanings associated with uneven development are re-articulated by elites—even at the local level—in their formation of oligarchic social relations. Rather than addressing the structural roots of inequalities that produce crises and discontents, populist projects mainly protect elite interests.

At the same time, many citizens must survive on low and unstable incomes, without adequate access to social protection. New regulations have exacerbated citizens’ vulnerability. One example is Law No. 20/2020 (the Omnibus Law), which encourages the use of flexible labour arrangements to attract foreign investors. New forms of precarity, such as those tied to digitalization and the gig economy have normalized the deprivation of workers’ of basic rights. Dangerous forms of work have become the backbone of state-backed projects, while facilitating rent-seeking arrangements that serve entrenched elite networks.

Subianto’s presidency has introduced several populist policies including “Free Healthy Meals” for students and vulnerable groups, and “Red and White Cooperatives” to promote local community economic empowerment. Nonetheless, income stagnation, especially among the middle class, persists.

The Temporary Coherence

Against this backdrop, the announcement of parliamentary members’ exorbitant allowances in mid-August 2025 exposed the stark gap between the lavish lifestyle of government officials and the shrinking resources devoted to the welfare of citizens. The killing of Affan Kurniawan, a ride-hailing motorbike (ojol) driver by police during a demonstration, followed by further incidents of killings and arrests of citizens and the banning of social media accounts, intensified public outrage over state coercion. This resulted in a temporary moment of popular coherence, where various groups of people managed to piece together fragments of understanding into collective understanding of systemic problems.

In a brief moment of unity, thousands ojol drivers participated in a convoy that escorted Affan to his funeral and chanted demands for justice over the incident. Student groups forged solidarity with ojol drivers to oppose state brutality. Ojol drivers, in turn, joined students and other collectives in voicing discontent over job scarcity, institutional distrust, as well as concerns about police and military power.

The colors “brave pink” and “hero green” emerged across digital platforms (TikTok, Instagram, and X) and street protests (banners, posters). “Brave pink” represents the veil worn by Ibu Anna, an ordinary mother, whose image confronting a police barricade with a stick and an Indonesian flag during a demonstration in front of the parliamentary building, was celebrated online. Meanwhile, “hero green” refers to the helmet worn by the fallen ojol driver Affan, whose death was mourned across online spaces through the phrase dilindas (run over) and ditindas (oppressed).

A group of social media influencers summarized the initially scattered demands of individual activists and academics and students, labour, pro-democracy, women groups into the 17+8 demands. Pros and cons leading up to the formation of the demands reflect the contested ways through which grievances are articulated. The ultimate mobilization of the 17+8 demands as the movement’s slogan facilitated the absorption of the demands of previous protests. This extended the demands of previous protests across diverse groups, thus reflecting a shared framework that helped define commonly shared discontents.

For instance, demands 1, 12-14, all directed toward the president and the military, call for an end to the military’s involvement in civil security and civilian affairs. This echoes concerns over the reassertion of military power in post-authoritarian Indonesia, as articulated, among others, through large-scale protests that took place in March 2025. Demands 15-17 call on the ministries of manpower, finance, and others to ensure decent wages, to prevent mass layoffs and to initiate dialogue with unions. Such demands, along with concerns over the return of military dominance, show continuity with demands that emerged among labour unions and civil society organizations in previous protests, including those against the implementation of the Omnibus Law in 2020.

Re-Articulation of Grievances

Nonetheless, radical theorists remind us that meaning is not inherent but is constructed by linking ideas and social practices in unstable ways. The meanings and understandings of grievances are continually redefined from “below” — across grassroots activists and organizations — and from “above” — by elite networks — within the oligarchic social formation. While this allows diverse movement groups to temporarily coalesce around a coherent articulation, oligarchic factions can diffuse and reorient these articulations to advance their own interests.

We thus witness how expressions of grievances against state coercion and deepening inequality by app-based motorbike drivers, student and other groups were swiftly reappropriated through populist gestures. Subianto himself paid visits to Affan’s family, while publicly announcing donations to compensate for their loss. Meanwhile, ride hailing companies pledged financial support for Affan’s family. Across the region, police forces took part in solat gaib (Islamic prayers for the deceased). Heads of police offices set meetings with protesters, promising justice for the fallen driver. These gestures demonstrate elite re-appropriations of grievances in ways that are intended to pacify the public’s anger, albeit without addressing structural inequalities and the very systemic violence that triggered the protests in the first place.

The deployment of populist programs helps to coop shared grievances. In September 2025, the government announced a 50 percent discount on the state-sponsored employment insurance (BPJS Ketenagakerjaan) premium, with ojol drivers designated as the main target. In October 2025, the Ojol Kamtibmas program — translated roughly as Ojol Drivers For Public Security — was launched, recruiting hundreds of thousands of drivers as civilian auxiliaries to partner with ride-hailing companies and police forces in crime reporting and prevention efforts.

Through the BPJS premium discount, workers’ discontents are absorbed and rearticulated into renewed legitimacy for the state. Meanwhile, the Ojol Kamtibmas program rearticulates workers’ expression of political solidarity against state brutality into support for the police amid ongoing contests among elite networks backed by the police and the military that have intensified in post-authoritarian Indonesia. As major trade unions continue to mobilize against the military’s involvement in civilian life following amendments to the military law that triggered protests in March 2025, the positioning of some ojol drivers as police supporters further strained the already fragile relations between non-unionized gig workers and organized labour. It also sharpened divisions among those aligning themselves against the state’s coercive power, as manifested in the August 2025 protests.

The articulation and the rearticulation of grassroot grievances appears as a recurring pattern, from the 2020 anti-Omnibus Law protests to the March and August 2025 mobilizations. Returning to the 2020 protests, while they were initially sustained by a broad coalition of labour unions, gig workers, students, and youth groups, signs of fragmentation surfaced when several labour unions showed support for the law under the promise of tripartite negotiations despite its detrimental effects on labour and environmental protections. The Constitutional Court’s 2023 ruling to exclude employment regulations from the Job Creation Law likewise reflected intra-elite maneuvering, as legal concessions were granted only after unions leaders pledged support for the president.

Conclusion

Grassroots grievances often produce waves of mobilization in which diverse groups temporarily find shared frameworks to make sense of their marginalization. Yet contestations over the meanings attached to these grievances take place in contexts where marginalized groups, activists and organizations articulate the grievances in disjointed ways, shaped by varied material circumstances. Meanwhile, the populist reorientation of such grievances by elite networks help to consolidate oligarchic social formations.

This leaves us with the task of unpacking how political subjects do not confront structural problems in the abstract but through localized everyday practices within historically shaped spaces and temporalities. Notwithstanding political subjects’ positions within nexuses of multiple, often contradictory forces and relations, it is crucial to trace how new links emerge while old ones dissolve amid moments of coherent and incoherent articulations. The 2025 mobilizations exemplify how fleeting coherence emerged from disjointed articulations of grievances. They materialized through evolving connections that unfolded beyond the mobilizations themselves, within the everyday, historically shaped lives of political subjects.

Diatyka Widya Permata Yasih is assistant professor at Department of Sociology and co-director of Asia Research Centre, Universitas Indonesia (ARC UI). Inaya Rakhmani is associate professor at Department of Communication and inaugural director of ARC UI.