In late November, mass public protests erupted in numerous Chinese cities following a building fire in Urumchi. Angry citizens and students took to the streets and voiced their anger and frustration against the country’s zero-Covid policy and political censorship. During and in the immediate aftermath of these protests, the overall silence of China’s public intellectuals was worth noting. Given China’s strict media and cultural censorship, in tandem with the backlash against the writer Fang Fang at the start of the pandemic, such silence was probably not so surprising. But this did not mean that literature and culture played no role in China’s public protests. Instead, we witnessed a proliferation of protest slogans, poems, essays, songs, and artworks, most of which were created by ordinary citizens and university students from China and globally. This essay presents some of the poems publicly circulated online and on social media to demonstrate the use of protest poetry in contemporary China.

Amongst all the recent protests in Chinese cities, the one on Urumchi Road in Shanghai was probably the most prominent. This was perhaps a reflection of the symbolic significance of Shanghai in the country’s geopolitics. Arguably, the protest in Shanghai was among the most politically sensitive ones, as some protesters demanded the resignation of Xi Jinping and the end of the one-party rule in China. Shanghai protesters made the link between people’s sufferings in the two cities: Shanghai and Urumchi. On the night of 26 November 2022, a piece of A4 paper was posted on the Urumchi Road sign, and the paper contained an untitled, four-line, hand-written poem:

乌鲁木齐的朋友

我爱你们

就像爱这条路

就像爱我的家人

Friends in Urumchi

I love you

Just as I love this road

and my own family members.

Regardless of whether the protesters knew about what had happened in Xinjiang in the past six years, the fire in Urumchi became a rallying point for them to publicly articulate intercity and interethnic solidarity between Shanghai and Urumchi and between the Han majority and the Uyghur minority. Although the poem was taken down from the road sign not long after it had been put up, the picture was uploaded on social media and circulated on the Internet, which continues the poem’s life journey in the subsequent national and global protests.

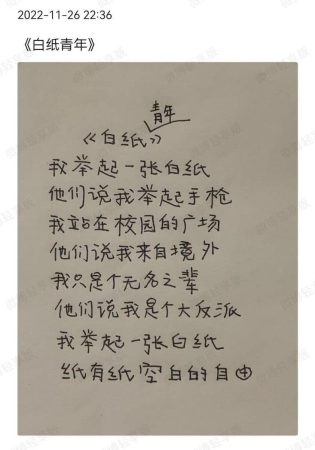

Holding a blank piece of A4 paper was a powerful symbol of protest against China’s political and cultural censorship in recent events. Blank paper has also been used to write protest slogans and poems on. These poems were often handwritten and anonymous, showing the spontaneous but sensitive nature of the act and the human touch of the protesters and representing the multitudes of ordinary people they represented. The following poem, titled ‘Blank-Paper Youth,’ offers a justification for the use of blank paper in these protests:

我举起一张白纸

他们说我举起手枪

我站在校园的广场

他们说我来自境外

我只是个无名之辈

他们说我是个大反派

我举起一张白纸

纸有纸空白的自由

I’m holding a blank piece of paper.

They say I’m holding a gun.

I’m standing at the campus square.

They say I come from overseas.

I’m just an insignificant ordinary person.

They say I’m a big counterrevolutionary.

I am holding a blank piece of paper.

Every piece of paper has its right to remain blank.

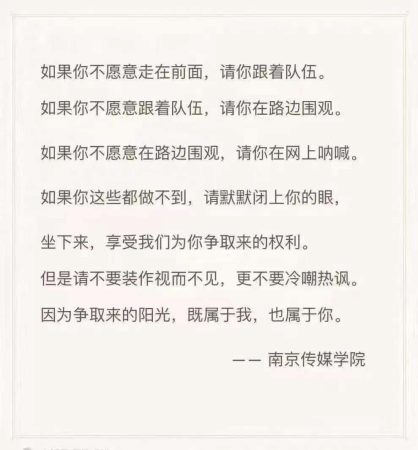

Students from more than fifty Chinese universities and numerous international universities participated in the protests. Protest poetry was used to recruit participants and rally bystander support. The following poem first appeared at the Communication University of China, Nanjing:

如果你不愿意走在前面,请你跟着队伍。

如果你不愿意跟着队伍,请你在路边围观。

如果你不愿意在路边围观,请你在网上呐喊。

如果你这些都做不到,请默默闭上你的眼,

坐下来,享受我们为你争取来的权利。

但是请不要装作视而不见,更不要冷嘲热讽。

因为争取来的阳光,既属于我,也属于你。

If you don’t want to take the lead, please follow the crowd.

If you don’t want to follow the crowd, please stand by the roadside.

If you don’t want to stand by the roadside, please voice your support online.

If you can’t do any of these, please close your eyes in silence,

sit down and enjoy the rights we’ve fought for you.

But please don’t pretend not to see things, or even mock us.

The sunshine we’re fighting for belongs to me, and you.

— Communication University of China, Nanjing

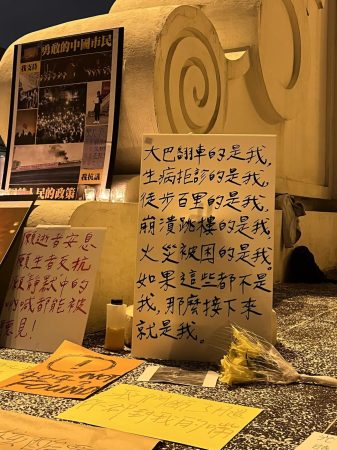

The following poem was first seen at the Northwest University of Political Science and Law in Xi’an, where a student held a placard at a local PCR test station. The poem was subsequently quoted in several candlelight vigils outside China. Its emphasis on the tremendous human cost of China’s stringent pandemic policy was particularly powerful:

大巴翻车的是我,

生病拒诊的是我,

徒步百里的是我,

崩溃跳楼的是我,

火灾被困的是我,

如果这些都不是我,

那么接下来就是我。

It was I who fell victim to the coach accident.

It was I who was denied medical treatment despite my illness.

It was I who had to walk home on foot for hundreds of miles.

It was I who was driven to the brink of despair and had to jump off a building.

It was I who was trapped in a burning inferno.

Even if I wasn’t among any of them,

I would follow them soon afterwards.

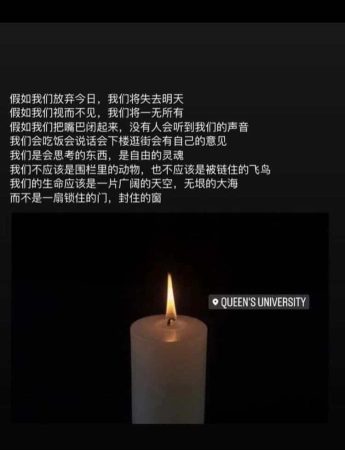

The following poster used for a candlelight vigil has Queen’s University’s name on it. Against a black background and above the picture of a burning candle is an untitled poem:

假如我们放弃今日,我们将失去明天

假如我们视而不见,我们将一无所有

假如我们把嘴巴闭起来,没有人会听到我们的声音

我们会吃饭会说话会下楼逛街会有自己的意见

我们是会思考的东西,是自由的灵魂

我们不应该是围栏里的动物,也不应该是被链住的飞鸟

我们的生命应该是一片广阔的天空,无垠的大海

而不是一扇锁住的门,封住的窗。

If we give up today, we’ll lose tomorrow.

If we turn a blind eye to everything, we’ll end up with nothing.

If we shut our mouths, no one will hear our voices.

We can eat and speak and go downstairs shopping and have our own opinions.

We’re thinking beings with free souls.

We shouldn’t be treated as fenced animals or chained birds.

Our life should be a broad sky or a boundless sea

and not a locked door or a sealed window.

As we can see from the above examples, selective and incomplete as they are, ordinary people including Chinese citizens and university students have used protest poetry to express their anger and sadness, and rally public and peer support in recent Covid protests in and outside of China. One can perhaps debate on the literray merits of these poems but this does not undermine their social significance. In an age where the public interllectural’s role is often unclear and poetry is often seen as an obsolete, high cultural form, perhaps we should reconsider the importance of interllecturals—in the forms of organic, grassroots or minjian interllecturals—as well as the use of literature in our tulmetous times.

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.