I-Yi Hsieh, Flora & Fauna: Domestic Nature and Private Collecting in Reform Era Beijing (Palgrave Macmillan, 2025)

“The Customer”, a prize-winning painting from 1990, depicts a middle-aged man holding a glass fishbowl. A young shopkeeper, family members and the budding aquarium hobbyist himself all appear transfixed by two goldfish swimming in the bowl at the center of the image. Judith Farquhar characterizes this artwork as an example of an “apolitical hobby” that replaced the epic depictions of collective labor favored by artists in Maoist China. I-Yi Hsieh’s delightful Flora and Fauna: Domestic Nature and Private Collecting in Reform Era Beijing (Palgrave Macmillan, 2025) offers a very different understanding of the significance of human and non-human relations forged in China’s “insect-flower-fish-bird” markets.

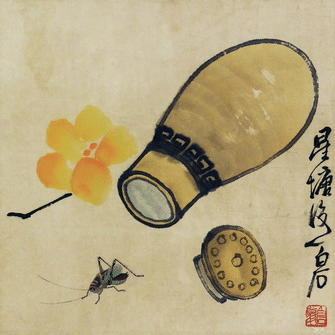

Hsieh’s book is, first and foremost, an ethnography of Old Beijing collecting (shoucang). The shop owners featured in this account do not belong to the wealthy urban elite or the migrant communities who are periodically expelled from the city. Instead, the congregation of connoisseurs who rent stalls in massive state-supported markets include former taxi drivers, grocers, handymen and others who hail from “down below” but nevertheless understand themselves as heirs to Old Beijing cultural history. In creating collaborative multisensory worlds with the help of goldfish, insect gourds, literati walnuts, and crickets, this group embraces the labors of breeding, tuning, feeding, and housing a range of non-human objects. The reward for excelling in these arcane pursuits is significant: connoisseurs who raise prized crickets emitting a refined hum that sounds like spring water can make hundreds of US dollars for the sale of a single insect. Hsieh, however, insists that these collectors are “obsessed” not with the money such business might bring, but rather, their commitment to cultivating multispecies milieu that serve as a shield against the harsh, frenetic environments they navigate in 21st century Beijing.

The book makes the case that documenting Old Beijing-inspired human-nonhuman relationships can help to dispel the Euro-American “natural order of things” that continues to insist on a separation of nature and culture. In conversation with the writings of Benjamin, Descola, Latour, Lefebvre, Mol, Merleau-Ponty, Munn and Winnicott, Hsieh works to destabilize purportedly universal categories. Her discussion of the collectors’ multispecies urban worldmaking engages two broad types of materialism—Marxist scholarship and recent object-oriented ontology—to elucidate collectors’ distinct set of ethical and ontological commitments. An accomplished curator as well as anthropologist, Hsieh’s theoretical agenda is complemented by the care and fascination with which she approaches these Beijing connoisseurs and their objects. Her vivid ethnographic descriptions of collecting practices are bolstered by the incorporation of Ming and Qing archival records, descriptions of street scenes, as well as the literary commentary of 20thcentury writers such as Lao She. The result is a compelling documentation of how the reconfiguration of objecthood offers practitioners new ways of situating themselves in continually transforming urban space.

Chapter Three, “Tanked Fish and Aquatic Happiness” offers a particularly powerful illustration of Hsieh’s project. The chapter starts with a vision of Chinese domestication that ties together “human, water, and fish as a system” (77). A dialogue between Zhuangzi and Huizi about the possibility of knowing “the happiness of the fish” grounds the subsequent exploration of the ecology required for the successful cultivation of prized red-goose head imperial goldfish in contemporary Beijing. In delineating the ecological system that supports this collective thriving, Hsieh moves from a discussion of the “metabolic labor” of the fish to the water-filled barrels preferred by prize-winning vendors, to the city’s distinctive centuries-old aquatic infrastructure. She then describes a visit to an urban village on the outskirts of the city where 187 breeding stations are staffed by migrant workers engaging in a painstaking labor of caring for the young fish that subsequently make their way to shops and collectors’ homes. The chapter powerfully conveys the appeal of“aquatic happiness” through domesticating nature in the city while revealing stark inequalities in the treatment of human workers who help to create and maintain this aesthetic world.

In the penultimate chapter, Hsieh shifts her focus from collectors to street performers. Initially celebrated as the freakish “Eight Great Marvels” in the last decades of the Qing empire, generations of performers have been subjected to shifting narratives and accompanying transformations to public spaces. In the Republic era, the performers were depicted as members of an abject lumpen proletariat before CCP media celebrated them as liberated workers in the first years of the People’s Republic. Today, wrestlers, xiangsheng comedy duos, dancers, and musical artists are feted as state-sanctioned ambassadors of the capital city’s intangible cultural heritage. Hsieh reads in their performances “historical hiccups” that unsettle their current status by revealing the historicity of earlier attempts to domesticate their marginalized traditions in China’s diverging projects of national becoming. The book culminates with a powerful critique of the contemporary “Chinese dream” as producing a chaotic and precarious existence for workers in the city that these worldmaking practices subtly subvert.

One nagging question I am left with after finishing the book involves the status of the feelings that the collectors and other figures in the text hold towards contemporary Chinese state actors. Despite Hsieh’s stated intention of avoiding an overly stark framing of Chinese citizens as “either collaborating with or resisting state power” (13), the book consistently insists that private collecting is an “implicit way of resisting” (101) and that expressive poetic worldmaking is one of “the only ways of being political within authoritarian censorship” (178). These characterizations don’t seem to allow for the possibility that collectors might hold a complex, contradictory feelings towards state actors. Silences that Hsieh reports exist among the collectors at certain points in her research might be less a direct fear of state reprisals than a hesitancy to articulate positions that diverge from those of the politically engaged Taiwanese anthropologist who is asking the questions. I was curious, too, about the relationships between the collectors and migrant laborers who supported their shops. These minor quibbles do not detract from the success of this exquisitely rendered ethnography of contemporary life in the capital. Moreover, Hsieh might respond by arguing that protecting a space for the “dialectics of self-making and world changing” in her account of Beijing collector aesthetic practices leaves open the possibility of making thecity a more inclusive, equitable place for all of its inhabitants.

Nick Bartlett is Assistant Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Asian and Middle East Cultures, Barnard College