Almost two years into the global pandemic of Covid-19, the contention surrounding wet markets as one of the pandemic’s outbreak origin narratives remains. Amid the furor of demanding that China put a blanket ban on wet markets, a rare agreement emerged among Mitch McConnell, Jane Goodall, Paul McCartney, and Anthony Fauci in March-May 2020. Declaring wet market as the literal and symbolic place of the “dirty, cruel, and primitive Asians” who butcher animals in public, hands and aprons covered in blood, a global discourse stigmatizing wet markets has peaked in the pandemic anxiety. Anthropologists have since attempted to combat these false charges by clarifying the point that the wild animal trade is a rare presence in the daily food markets of China, known as wet markets in English (Lynteris and Fearnley 2020). Some have gone further to argue that wet markets are a local way of food consumption that value neighborhood, face-to-face interactions while acquiring the benefit of reducing the over-packaging of food items commonly seen in supermarkets (Cheung 2020). What is missing in the two sides of global discourses pertinent to the issue at hand is the labor history of wet markets. This community-scaled food infrastructure is widely available not only in the People’s Republic of China, but also in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Southeast Asia, among other places. This is not to mention that the term “wet market” was first minted in official policy in Singapore in the 1970s, as the city-state began to differentiate air-conditioned supermarkets from food vendors using ice to keep produce fresh at the stall, in open-air temperatures. When the ice melted and sometimes dampened the market’s floor, there emerged the attribution of “wetness” in the term “wet market.” It is thus fair to argue that wet markets, as a category and a named social practice aimed at global translatability, is in and of itself a post-war invention.

The international advocates for a ban on wet markets amid the pandemic turns out to be evidence of a continuous Orientalism reinforced by the anti-China sentiment fueled by the pandemic. Looking back, it is now clear that wet markets were the scapegoat for the dismantled public health care system and other social problems looming underneath the just-on-time capitalism of our age. Even the contentious Huanan Seafood Market itself, now forced to close, was a wholesale food market mostly supplying restaurants and was a congregation of cross-province trucks and large refrigerators, with Wuhan being China’s inland hub city. This fact runs counter to the Euro-American ascription of the Huanan Seafood Market being a small, dirty “wet market” filled with random transactions. Instead, it was a well-organized wholesale organization managed by the Huanan Fruits Wholesale company with an investment amounting to about US$7.68 million. The scale of the marketplace itself is a story of contemporary China: it encompassed 50,000 square meters (12.36 acres) and in this sense, it resembled the textile, small merchandise, art, or even antique-collecting markets emblematic of the unique form of megasized wholesale commercial zones birthed in China’s market reform era. In 2011, the total trade at the Huanan Seafood Market amounted to US$183 million, [1] with the parent company of its management being a real estate corporation. It has even received the title of “Civilized Market in Wuhan” several times.[2] The main investors in the wholesale space include 24 corporations from Wuhan, Shanghai, and Beijing.

What about Taiwan?

Since mid-2020, I have started to conduct ethnographic fieldwork at several wet markets in Taipei—first initiated as a rebuttal to the global stigmatization of wet markets as a global biosecurity risk embedded in the capitalist food system. Indeed, local food markets in Asia are now deeply woven into the international food system and cargo logistics, while they also employ a large labor force to process animal meats and produce on behalf of Asia’s rising urban consumers alienated from the complex, and highly uneven food production process. Yet fieldwork has its own ontogenesis to surprise a researcher. I gradually found that the issues surrounding biosecurity always point to biopolitics. It is not only true that the flow of air in outdoor markets helps to reduce the aerosol transmission of the Covid-19 virus, which makes the outdoor wet markets in Taiwan a safer space to shop than supermarkets and the government-managed indoor compounds, both of which are sometimes located in basements with cramped stalls in an environment of bad ventilation. It is also true that the labor history and friction over wet market vendors is very telling of Taiwan society’s tangled relationship with capitalism through the colonial to post-war times.

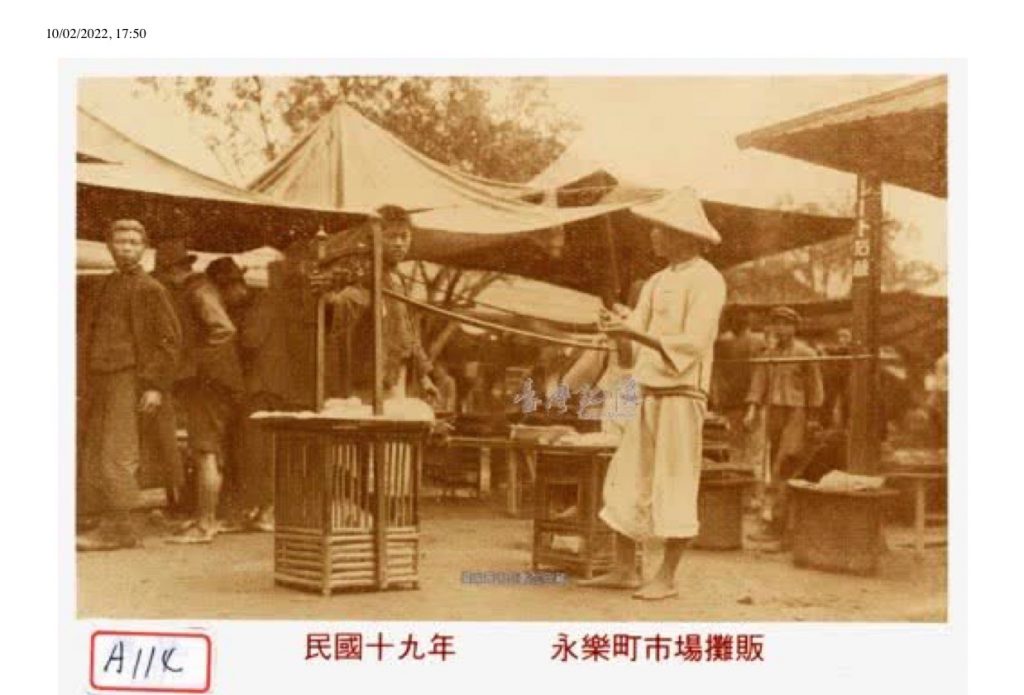

As anyone who has ever been to Taiwan would know, the gigantic, indoor compounds dressed up in a Cold War architectural style of bureaucratic mono-color (fifty shades of blue, if one may) have been the norm for public food markets in Taiwanese cities, designed to improve hygiene standards and managerial excellence. In researching the regulations on street markets in Taiwan, the archival work leads me to discovering that the Japanese colonial origin of indoor food markets was first designed to be a major tax revenue generating mechanism for the first Colonial Governor, who used the lucrative tax collected at colonial public markets and slaughter houses to fund his ambitious hygiene infrastructure implemented in the early 1900s. This first public, indoor marketplace was established in colonial Tainan in 1905, in a baroque style that even surpassed its Japanese counterparts established as late as the 1930s. In the Cold War era, the Nationalist government continued the colonial governmentality regarding street markets as a source of social chaos and hygiene concerns. Yet the more effort put into rounding up street vendors into indoor market compounds, often from their original neighborhood to far away locations, the more it seemed to be a futile attempt as new vendors would soon appear at the original wet market’s location. And of course, the unruliness of street vendors is a constant story of political tension in Taiwan. The most infamous case was the instigation of the 228 Incident in February1947 — when a 40-year-old woman Lin Jiang-mai, a vendor selling contraband cigarettes at a local street market in Taiheichō, was struck by the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau enforcement team trying to confiscate her cigarettes. Taiheichō was one of the known street market locations in the pre-Japanese Qing era, and it was such a popular designation that later the Japanese Colonial Governor set up an indoor market compound in the old street market’s location in 1908.

The Labor History of Wet Market

The labor history of wet markets in Taiwan is even more telling of the biopolitics of food infrastructure. In the anti-eviction activism for a wet market located in central Taipei in 2020-2021, the international friction on wet market embeds itself into the concrete, everyday struggle faced by the vendors and migrants whose lives are deeply entangled in these neighborhood-scale food supply organisms. Situated at the juncture of the old and new in central Taipei, the wet market of my fieldwork site, Shuanglian market, has been caught up in the storm of gentrification enhanced by Taipei municipal government’s zealous pursuit of rebranding Taipei as global city, which resulted in an infrastructure renewal aiming to replace community grassland alongside the wet market of about 200 vendors with a design claimed to be Tokyo “Shinjuku” style of trendiness. This design would cover the already over heated city center with cement surface throughout one subway line’s ground-level park. Initially, the excuse for eviction of the wet market went by branding the vendors an urban safety risk for potentially causing fire in the neighborhood and obstructing fire trucks getting through (an entirely false accusation as the open space of park by the wet market provides plenty of space for emergency evacuation). This excuse uncannily resembled the eradication of the so-called “low-end population” campaign that removed migrant communities in Beijing in 2017-2019.

In participating in the year-long protest launched by Shuanglian’s community members who support the wet market, I found the grassroot organizing among the vendors can surprise our dominant academic discourses regarding these day laborers as the precariat class. Our academic discourses often depict contingent labor in our time as “the dangerous class” who are hard to organize and prone to anti-social resentment. To the contrary, despite all the difficulties of organizing meetings, elections, and petitions among a group of high school dropouts, illiterate elders, Buddhist moms, southeast Asian vendors and neighborhood hooligans against a hoard of techno-bureaucrats and civil engineers from the Taipei Metro and municipal government, the wet market is like a sponge absorbing a variety of invisible livelihoods, providing everyone a place to labor, to connect and make a living. Indeed, after interviewing many vendors, I found a large percentage of them were once factory workers at textile or shoe factories who had been laid off when Taiwanese factories went overseas in droves in the 1990s, to mainland China or southeast Asia. Many vendors initially took up odd jobs and gradually found their way into these organically gathered wet market locations, catering for community-oriented food consumption by providing sophisticated, individualized service for housewives and seniors who frequent their familiar vendors.

What the Taiwan story tells us is that the local wet markets, called caishichang (菜市場) in mandarin, provide a social mechanism to digest the over-commodified factory workers created during the golden era of Taiwan’s manufacture-export in 1960s-1980s, who later were forced into unemployment during the first crisis of rising wages and living standards following the Taiwanese capitalists going overseas to reduce production cost in pursuit of higher profit. These day laborers were nonetheless first created by Taiwan’s “aiding the industry with agriculture (以農養工)” in the 1960s-70s, which forced peasant families to rely on one or more members working at factories, while the island’s special economic zones provided jobs for sewing shoes, making toys, or assembling chemical products for US companies such as Johnson & Johnson. Later, when these manufactures left for cheaper labor in the then opening People’s Republic of China, the workers in Taiwan found themselves falling into a precarious situation. Eventually many found their way into wet markets and night markets, where labor for food preparation arose to cater for the urban white-collar households. Despite the government’s consistent efforts to erase wet markets in major Taiwanese cities, the scale of outdoor food markets simply has continued to swell everywhere in the past twenty years, particularly at the margin of large metropolitan centers or in emerging technology towns such as Taipei and Hsinchu – where major IT companies like the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing reside. The mono-industry path launched in Taiwan in the past 30-40 years has indeed contributed to a flourishing engineer class working for the IT industry, yet this narrow concentration also abandons and leaves behind a generation of workers who were not included in the technology boom. So these workers turn to basic human needs: food and care, the things that every neighborhood needs and desires. It is thus no surprise that about 70% of this union of the vendors working at the Shuanglian market is female. And it is also no surprise for any labor scholar to anticipate that one major obstacle they face is confronting the Taipei municipal government’s initial ignorance and negligence of these vendors’ livelihood, rights to work, and well-being.

There is thus no surprise that wet markets exist in many Asian trade hub cities, for they serve as an organism absorbing surplus population. And this defines the social life of wet markets. The labor history of wet markets also calls for a perspective of multispecies ethnography, for the labor which is involved in the food production processes tends to be placed at the lower rung of the social hierarchy, alongside the produce and animals they deal with. They are categorized and denigrated by having to deal with the bodily fluids of animals, the unavoidable wetness, however much commodity fetishism tries to hide these material realities from the supermarket consumer by deploying ever more plastic packaging. It is thus also imperative to consider the biopolitics of wet markets as a problem of capitalist crisis converging with environmental crisis, particularly in light of Rob Wallace and others’ call to dwell analytically on the constant outbreaks of zoonotic pandemics of our time in the context of human’s increasing depriving wild animal of their habitats for urban expansion and industrial animal farms.

The global friction of wet markets urges us to confront capitalist surplus production and surplus population, articulated in the Marxist theories of crisis, in the increasingly solidified Asian urban household economy that outsources family food preparation and food care to wet markets in metropolitan areas. The laborers who carefully prepare a piece of pork at a pork stall in a wet market absorb a whole history of food infrastructure, and its stigma, in exchange for rising Asian urban consumers demanding freshly slaughtered meat for a dish on the dinner table. If we cannot consider wet markets in the origin outbreak narrative of Covid-19 as inevitably caught up by multispecies labor relations taking place at global trade hubs, against a backdrop of increased inequality embodied in the degradation of public health around the world, we might never see the end of enhanced pandemic cruelty, which defines a new horizon of (in)humanity in our time.

I-Yi Hsieh is a Postdoctoral Researcher, ICCS, Taiwan Yangming-Chiaotung University

NOTES

[1] See the Sina Finance report on the Huanan Seafood Market’s management team: https://cj.sina.com.cn/articles/view/1704103183/65928d0f02001iyab

[2] Ibid.