In November 2017, news flashed around the world about the defection of a North Korean soldier stationed in the Joint Security Area at the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating the two Koreas. Shot during the crossing, what made headlines was rather the parasitic worms found in his intestines during surgery. Humanitarian health workers know this is a common condition in the developing world, which can be prevented with access to safe water and sanitation, and treated with drugs or surgery if available, as in post-war Vietnam.

This case underscores the extent to which environmental crises are fraught with politics, both in the way domestic policies are framed within a country, and for North Korea in how its environment is understood and addressed by international actors from the United Nations to humanitarian organizations. In disregard of doctor-patient confidentiality, politicians and pundits used the public release of the details of the soldier’s health status to highlight difference in conditions between the two Koreas.

However, what is revealed in the tragic story is North Korea’s environmental crises. These include (1) the direct impact of the Korean War on its environment; (2) indirect impact of ongoing conflict on its capacity to handle these environmental problems; (3) and finally, the severe constraints on humanitarian organizations to address environmental factors of the health crises in North Korea (officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK).

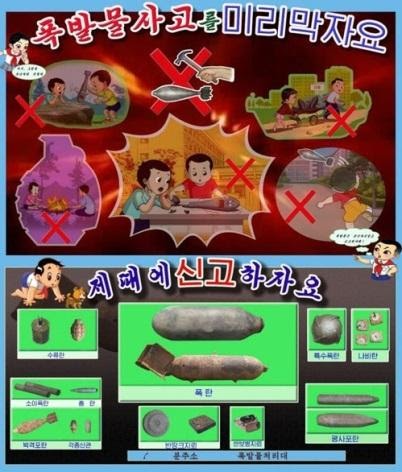

Symbolized by the soldier’s post along the DMZ, the first, direct result and continuing legacy of the Korean War are its remnants. A sustained bombing campaign in the three years between 1950 and 1953 levelled the country, leaving obvious environmental hazards but also many unexploded ordnance (UXO) embedded in the ground. North Korean authorities report that there have been over 16,215 victims of explosive remnants since the end of the war. Farmers are frequent victims of these exploding devices, particularly as the mines move during natural disasters such as floods and landslides.

Secondly, the gunshot wounds and the intestinal worms were not this soldier’s only medical problem. During a full examination he additionally presented with hepatitis, pneumonia, and malnutrition. Until the 1970s the North Korean government had been able to supply farmers with chemical fertilizers, but in the face of increasing economic hardship in subsequent decades, animal and human waste had to be used to secure food production, explaining the parasitic worms. By the 1990s and the dissolution of the Socialist bloc and thus the end of trade and oil subsidies, there was a devastating flood which led to a severe famine, known in North Korea as the Arduous March. Humanitarian groups responded to North Korea’s request for aid, but met with challenges as North Korea came under repeated sanctions.

Consequently, according to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), “an estimated 10.3 million people [in North Korea] suffer from food insecurity, under-nutrition and a lack of access to basic services” due to recurrent natural hazards that in 2018 included “a heatwave, a dry spell, a typhoon, floods and landslides” and a broad sanctions regime that has limited state access to such basic medical supplies as “vaccines, antiviral medicines, rapid testing kits, personal protective equipment for health workers and hand sanitizer.” This example illuminates how politicized differentiations between humanitarian and development aid based on separate funding sources constrain basic life processes and the soldier’s body vividly shows us what happens when supplies of fertilizer and provisions of clean water and sanitation facilities are discontinued.

On the other hand, North Korea’s predicaments are symptomatic of industrial agricultural production in general. Since its founding in 1948 until the early 1980s, North Korea had met its food needs. To compensate for its short growing season and the fact that only 18 percent of all land is arable, the state developed a decentralized system of cooperative farms, aided by capital investments in rural electrification, irrigation, mechanization, agro-chemicals, and hybrid seeds. Dependence on coal and hydropower plants, however, accelerated negative impacts on the environment, exacerbated by greater weather anomalies. Over reliance on chemical fertilizers resulted in soil acidification and thus decreasing yields. As previous plots produced less, more marginal lands and forests were cleared for production, leading to deforestation and soil erosion, worsened by foraging, directly contributing to more severe flooding. And still, facing these compounding problems, increasing sanctions over the last decade severely hamper North Korea’s ability to import new seeds and technology.

Historically, the common twentieth century drive for industrial development in the form of state-led developmentalism with an emphasis on heavy industries shaped North Korea’s environment. Like South Korea in the same period, this was North Korea’s policy between the 1960s and 1980s until the 1990s natural disasters and subsequent famine. This led to the imperative to supplement developmentalism with humanitarian aid. Caught between developmentalism and humanitarianism, its example shows just how inadequate these paradigms and categories are for addressing environmental issues, which no matter how good or bad the prevailing circumstances require long term solutions rather than short term developmental goals or humanitarian funding.

Climate change only increased the frequency of disasters and community exposure to the effects of deforestation, landslides, extreme weather, and more frequent and devastating floods, with debilitating consequences on food production. North Korea deals with serious flooding almost every year. Floods cause destruction and loss of lives, homes, and crops. At the same time, drought is common in the spring, coinciding with the rice planting season and affecting sensitive early crops. Thus, North Korea is one of the places most vulnerable to climate change, not only geographically as are parts of Africa, but also politically due to extreme sanctions. Consequently North Korea has little recourse. When access to resources to improve production, like fertilizers, irrigation, and technologies are restricted, even minute changes in weather patterns result in outsized impacts on food production and population sustainability.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) attributes vulnerability to climate change on three factors: exposure to hazards (such as reduced or increased rainfall), sensitivity to those hazards (such as farming dominated by rain-fed agriculture), and the capacity to adapt to hazards (for example, whether farmers have the money or skills to grow more drought-resistant crops). According to the IPCC, all three factors apply to North Korea, as confirmed by its own 2012 climate change report. Adaptation measures, such as better protection against floods, improved organization and connectivity within and between communities, and reinforced adaptive knowledge and capacity, are needed to reduce vulnerability. By sheer necessity then, North Korea has emerged as a “champion in the fight against climate change,” ratifying the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, or Convention) in 1994, the Kyoto Protocol in 2005, and the Paris Agreement in 2016. In 2019, the North Korean government established and completed its 2019-2030 national environment protection and disaster risk reduction strategies based on the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. However, the cost of major infrastructure reinforcement often exceeds national resources and the current sanctions against North Korea pose major challenges.

The everyday reality in North Korea reflects global patterns of the developing world in which the top causes of infant and childhood mortality are diarrhea and acute respiratory infections due to lack of access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation (for almost 40 percent of the population), while cases of pneumonia and tuberculosis are on the rise due to malnourishment and shortage of food, as well as lack of medicines, with more than 5.6 million North Korean people (almost a quarter of the entire population) affected by natural disasters between 2004 and 2015. These and not the mainstream media emphasis on nuclear issues pose the most urgent concern to North Koreans and consequently to the world.

In 1995, the DPRK Red Cross requested international support from members of the IFRC for the first time, following the major flood disaster. An IFRC delegation was established and has since then remained in Pyongyang staffed with 6 internationals and 20 Korean nationals. The initial large scale response focused on food and non-food essentials distribution. Over time the Red Cross developed annual community based programs supported by the IFRC, centered on restoration of water supplies to health clinics and households in cooperative farms, distribution of essential drugs and basic medical equipment to over 8 million people in 2,000+ village level clinics and county level hospitals, as well as comprehensive disaster preparedness in allocated geographical areas. The local community’s own contributions to the programs have been massive and continuous; they provide all labor without financial compensation, and mobilization may involve thousands of villagers to install several kilometers of pipe, plant tree saplings over large areas, or to build mitigation structures against floods. Despite these local measures, international procurement of material like pipes, pumps, and transformers can take up to six months, and does not include the time taken applying for sanctions exemptions. This leads to chronic crises.

In 2005, the North Korean government officially informed international organizations including the IFRC that the country sought to transition from humanitarian assistance to international cooperation on development and sustainability. This request ran into a familiar road block. When funding streams are, for political reasons, restricted to short term (6-12 months) humanitarian budgets, how is it possible to engineer long term, developmental programs. On national security grounds, North Korea could not meet the requirements for banking transparency, external audits of ministry bodies and strict financial regulations required by development cooperation financing instruments.

And yet, somehow, the Red Cross began community support with simple vegetable greenhouses in 2007, in line with policy directions from the North Korean government. Often managed by trained disadvantaged women from the community (e.g. women from poorer families, female headed households, women with many children, women with disabilities), this project has increased production of fresh vegetables during longer periods of the year and provided a more diverse diet to vulnerable groups. In 2012, a small pilot project commenced for more integration of community programs toward long term sustainability, with seed funds from the Norwegian and Swedish governments as well as the German Embassy in Pyongyang. The Red Cross also applied learning from an exchange mission to Nepal, where the Nepalese Red Cross carries out similar programs led by communities themselves. Learning from the pilot project led to a standard program called the Integrated Community Development Programme (ICDP), with a combination of programs such as disaster preparedness and risk reduction; community based health and first aid; water, sanitation and hygiene promotion; livelihood through greenhouses and reforestation. Over time, the greenhouses have become more substantial and technologically innovative; for instance, through the use of solar energy favored by the government as part of its push toward renewable energy.

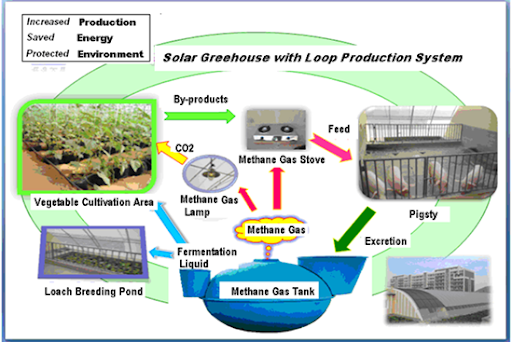

Building on the last ten years’ experience, the Red Cross and the DPRK Academy of Science are implementing an EU funded Food Security Project, which includes international technological exchange and capacity building drawing on expertise from European based organizations. In the project plan, the construction of an integrated solar greenhouse with a loop production system is included as shown in the diagram below. This model incorporates breeding of pigs and fish, and the production of methane gas as by-products for vegetable production.

After 70 years of protracted conflict in Korea, the situation is critical for people’s livelihood as well as for the environment on the Korean peninsula, although environmental issues are not North Korea’s problems alone. The persistent focus on output in the history of industrial agriculture has depleted the soil throughout the world, even as climate change further accelerates food shortages. Depleted soils are proof of an agrarian history of mismanaged land use, foreshadowing a grim future for agriculture and food availability worldwide. Enormous investments in “green manure” – grown as nitrogen-fixing crops that is worked into the soil rather than harvested – would be required for sustainable agriculture. But given the short term goals and needs to maximize harvests, North Korea has followed the path of the developing world.

From early warnings of increasing weather anomalies and the adverse impact on food production worldwide to the environmental dangers of weapons of mass destruction, North Korea has followed the debate about climate change and its social impact much more closely than one might expect given its current political standing in the world. Parallel to its nuclear weapons program in the last decade, North Korea has also been an active participant and advocate of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, voting in 2016 in favor of starting UN negotiations to ban nuclear weapons although it has yet to sign the new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons that opened for signatures in 2017.

The inconsistencies reflected in North Korean nuclear policy is symptomatic of the contradictions inherent to nuclear technology, which for under-resourced countries like North Korea can mean both energy and deterrence. If the current model of development and food production – as well as nuclear confrontation – is ultimately unsustainable not just for North Korea but globally, then sustained effort and international cooperation are necessary as demonstrated by North Korea’s own efforts to find a path toward “sustainable and resilient human development.” Between the obsolete models of developmentalism and the conventional stopgap measures provided by humanitarianism in the aftermath of developmental failures, the integrated approaches of local first responders like the Red Cross that focus on community development offer a model of sustainability that accounts for our symbiotic relationship with the environment.