Edward Said was no tree hugger. Descended from traders, artisans, and professionals, the great anticolonial intellectual once described himself as “an extreme case of an urban Palestinian whose relationship to the land is basically metaphorical.” In After the Last Sky, his meditation on the photographs of Jean Mohr, he explored the most intimate aspects of Palestinian lives, from hospitality to sports to home décor. The tiniest detail (the placing of a picture frame, the defiant posture of a child) provoked a torrent of insight from Said. Yet, when he was confronted with images of Palestinian farmers (tending their flocks, working the fields), the specificity suddenly evaporated. Which crops were being cultivated? What was the state of the soil? The availability of water? Nothing was forthcoming. “I continue to perceive a population of poor, suffering, occasionally colorful peasants, unchanging and collective,” Said confessed. This perception was “mythic,” he acknowledged—yet it remained.

If farming was another world for Said, those who devoted their lives to matters like air and water pollution appear to have inhabited another planet. Speaking to his colleague Rob Nixon, then at Columbia University, he once described environmentalism as “the indulgence of spoiled tree huggers who lack a proper cause.” But the environmental challenges of the Middle East are impossible to ignore for anyone immersed, as Said was, in its geopolitics. This is a region intensely vulnerable to heat and water stress, to sea-level rise and to desertification. A recent paper in Nature Climate Change predicts that unless we radically lower emissions and lower them fast, large parts of the Middle East will likely “experience temperature levels that are intolerable to humans” by the end of this century. And that’s about as blunt as climate scientists get. Yet environmental issues in the region still tend to be treated as afterthoughts, or luxury causes. The reason is not ignorance, or indifference. It’s just bandwidth. Climate change is a grave threat, but the most frightening impacts are a few years away. In the here and now, there are always far more pressing threats to contend with: military occupation, air assault, systemic discrimination, embargo. Nothing can compete with that; nor should it attempt to try.

There are other reasons that environmentalism might have looked like a bourgeois playground to Said. The Israeli state has long coated its nation-building project in a green veneer—it was a key part of the Zionist “back to the land” pioneer ethos. And in this context, trees, specifically, have been among the most potent weapons of land grabbing and occupation. It’s not only the countless olive and pistachio trees that have been uprooted to make way for settlements and Israeli-only roads. It’s also the sprawling pine and eucalyptus forests that have been planted over those orchards, and over Palestinian villages. The most notorious actor on this has been the Jewish National Fund, which, under its slogan, “Turning the Desert Green,” boasts of having planted 250 million trees in Israel since 1901, many of them nonnative to the region. It has also directly funded key infrastructure for the Israeli military, including in the Negev Desert. In publicity materials, the JNF bills itself as just another green NGO, concerned with forest and water management, parks and recreation. It also happens to be the largest private landowner in the state of Israel, and despite a number of complicated legal challenges, it still refuses to lease or sell land to non-Jews.

I grew up in a Jewish community where every occasion (births and deaths, Mother’s Day, bar mitzvahs) was marked with the proud purchase of a JNF tree in the name of the honored person. It wasn’t until adulthood that I began to understand that those feel-good faraway conifers, certificates for which papered the walls of my Montreal elementary school, were not benign—not just something to plant and later hug. In fact, these trees are among the most glaring symbols of Israel’s system of official discrimination, the one that must be dismantled if peaceful coexistence is to become possible.

The JNF is an extreme and recent example of what some call “green colonialism.” But the phenomenon is hardly new; nor is it unique to Israel. There is a long and painful history in the Americas of beautiful pieces of wilderness being turned into conservation parks, and then that designation being used to prevent Indigenous people from accessing their ancestral territories to hunt and fish or simply to live. It has happened again and again. A contemporary version of this phenomenon is the carbon offset. Indigenous people from Brazil to Uganda are finding that some of the most aggressive land grabbing is being done by conservation organizations. A forest is suddenly rebranded a carbon offset and is put off-limits to its traditional inhabitants. As a result, the carbon offset market has created a whole new class of green human rights abuses, with farmers and Indigenous people being physically attacked by park rangers or private security when they try to access these lands. Said’s comment about tree huggers should be seen in this context. […]

Perhaps this puts the cynicism about the green movement in context. People do tend to be put off when their lives are treated with less respect than flowers and reptiles. And yet there is so much of Said’s intellectual legacy that both illuminates and clarifies the underlying causes of the global ecological crisis, so much that points to ways we might respond that are far more inclusive than current campaign models: ways that don’t ask suffering people to shelve their concerns about war, poverty, and systemic racism and first “save the world,” but that instead demonstrate how all these crises are interconnected, and how the solutions could be, too. In short, Said may have had no time for tree huggers, but tree huggers must urgently make time for Said, and for a great many other anti-imperialist, postcolonial thinkers, because without that knowledge, there is no way to understand how we ended up in this dangerous place, or to grasp the transformations required to get us somewhere safer. So, what follows are some thoughts, by no means complete, about what we can learn from reading Said in a warming world.

He was and remains among our most achingly eloquent theorists of exile and homesickness, but Said’s homesickness, he always made clear, was for a home that had been so radically altered that it no longer really existed. His position was complex: he fiercely defended the right of Palestinians to return, but never claimed that home was fixed. What mattered was the principle of respect for all human rights equally and the need for restorative justice to inform our actions and policies. This perspective is deeply relevant in our time of eroding coastlines, of nations disappearing beneath rising seas, of the coral reefs that sustain entire cultures being bleached white, of a balmy Arctic. This is because the state of longing for a radically altered homeland, a home that may not even exist any longer, is something that is being rapidly, and tragically, globalized.

In March 2016, two major peer-reviewed studies warned that sea level rise could happen significantly faster than previously believed. One of the authors of the first study was James Hansen, perhaps the most respected climate scientist in the world. He warned that, on our current emissions trajectory, we face the “loss of all coastal cities, most of the world’s large cities and all their history”—and not in thousands of years from now but as soon as this century. In other words, if we don’t demand radical change, we are headed for a whole world of people searching for a home that no longer exists.

Said helps us imagine what that might look like as well. He often invoked the Arabic word sumud (“to stay put, to hold on”), that steadfast refusal to leave one’s land despite the most desperate eviction attempts and even when surrounded by continuous danger. It’s a word most associated with places like Hebron and Gaza, but it could be applied equally today to thousands of residents of coastal Louisiana who have raised their homes up on stilts so that they don’t have to evacuate, or to Pacific Islanders whose slogan is “We are not drowning. We are fighting.” In low-lying nations like the Marshall Islands and Fiji and Tuvalu, they know that so much sea level rise is already locked in from polar ice melt that their countries likely have no future. But they refuse to concern themselves with only the logistics of relocation, and wouldn’t relocate even if there were safer countries willing to open their borders—a very big if, given that climate refugees aren’t currently recognized under international law. Instead, they are actively resisting: blockading Australian coal ships with traditional outrigger canoes, disrupting international climate negotiations with their inconvenient presence, demanding far more aggressive climate action. If there is anything worth celebrating in the Paris Climate Agreement—and sadly, there isn’t enough—it has come about because of this kind of principled action: climate sumud.

But this only scratches the surface of what we can learn from reading Said in a warming world. He was, of course, a giant in the study of “othering,” what is described in his 1978 book Orientalism as “disregarding, essentializing, denuding the humanity of another culture, people or geographical region.” And once the other has been firmly established, the ground is softened for any transgression: violent expulsion, land theft, occupation, invasion. Because the whole point of othering is that the other doesn’t have the same rights, the same humanity, as those making the distinction. What does this have to do with climate change? Perhaps everything.

We have dangerously warmed our world already, and our governments still refuse to take the actions necessary to halt the trend. There was a time when many had the right to claim ignorance. But for the past three decades, since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created and climate negotiations began, this refusal to lower emissions has been accompanied with full awareness of the dangers. And this kind of recklessness would have been functionally impossible without institutional racism, even if only latent. It would have been impossible without Orientalism, without all the potent tools on offer that allow the powerful to discount the lives of the less powerful. These tools—of ranking the relative value of humans—are what allow the writing off of entire nations and ancient cultures. And they are what allowed for the digging up of all that carbon to begin with.

Fossil fuels aren’t the sole driver of climate change—there is also industrial agriculture and deforestation—but they are the biggest. And the thing about fossil fuels is that they are so inherently dirty and toxic that they require sacrificial people and places: people whose lungs and bodies can be sacrificed to work in the coal mines, people whose lands and water can be sacrificed to open-pit mining and oil spills. As recently as the 1970s, scientists advising the US government openly referred to certain parts of the country being designated “national sacrifice areas.” Think of the mountains of Appalachia, blasted off for coal mining because so-called mountaintop removal coal mining is cheaper than digging holes underground. There must be theories of othering to justify sacrificing an entire geography—theories about the people who lived there being so poor and backward that their lives and culture don’t deserve protection. After all, if you’re a “hillbilly,” who cares about your hills? […]

The point is this: our fossil fuel–powered economy requires sacrifice zones. It always has. And you can’t have a system built on sacrificial places and sacrificial people unless intellectual theories that justify their sacrifice exist and persist: from the Doctrine of Christian Discovery to Manifest Destiny to terra nullius to Orientalism, from backward hillbillies to backward Indians. We often hear climate change blamed on “human nature,” on the inherent greed and shortsightedness of our species. Or we are told we have altered the earth so much and on such a planetary scale that we are now living in the Anthropocene, the age of man. These ways of explaining our current circumstances have a very specific, if unspoken meaning: that humans are a single type, that human nature can be essentialized to the traits that created this crisis. In this way, the systems that certain humans created, and other humans powerfully resisted, are completely let off the hook. Capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy—those sorts of systems.

Diagnoses like this also erase the very existence of human systems that organized life differently, systems that insist that humans must think seven generations in the future; must be not only good citizens but also good ancestors; must take no more than they need and give back to the land in order to protect and augment the cycles of regeneration. These systems existed and persist, against all odds, but they are erased every time we say that climate disruption is a crisis of “human nature” and that we are living in the “age of man.” […]

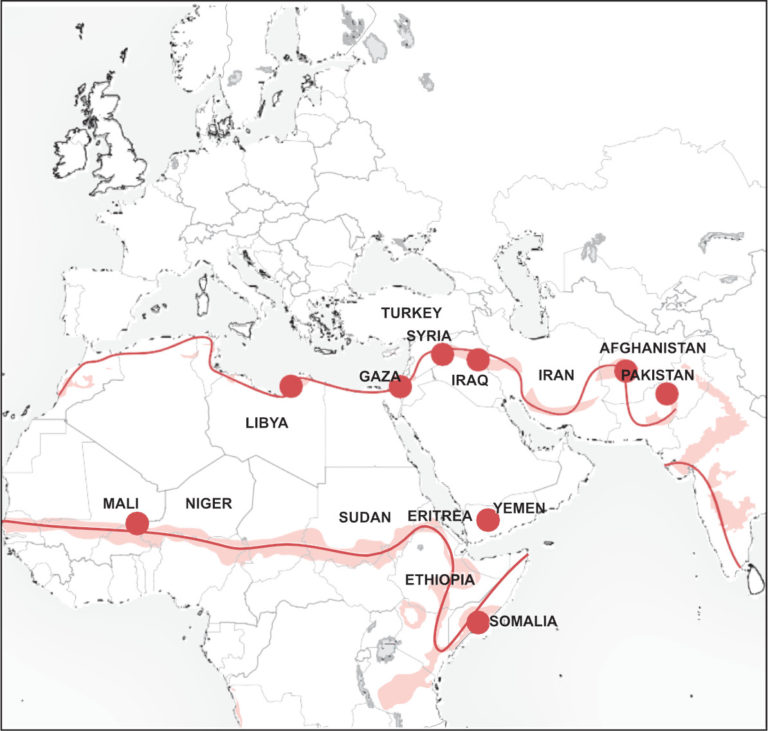

This is an emergency, a present emergency, not a future one. […] The most important lesson to take from all this is that there is no way to confront the climate crisis as a technocratic problem, in isolation. It must be seen in the context of austerity and privatization, of colonialism and militarism, and of the various systems of othering needed to sustain them all. The connections and intersections between them are glaring, and yet so often, resistance to them is highly compartmentalized. The anti-austerity people rarely talk about climate change; the climate change people rarely talk about war or occupation. Too many of us fail to make the connection between the guns that take black lives on the streets of US cities and in police custody and the much larger forces that annihilate so many black lives on arid land and in precarious boats around the world.

Overcoming these disconnections, strengthening the threads tying together our various issues and movements, is, I would argue, the most pressing task of anyone concerned with social and economic justice. It is the only way to build a counterpower sufficiently robust to win against the forces protecting the highly profitable but increasingly untenable status quo. Climate change acts as an accelerant to many of our social ills (inequality, wars, racism, sexual violence), but it can also be an accelerant for the opposite, for the forces working for economic and social justice and against militarism. Indeed, the climate crisis, by presenting our species with an existential threat and putting us on a firm and unyielding science-based deadline, might just be the catalyst we need to knit together a great many powerful movements bound together by a belief in the inherent worth and value of all people and united by a rejection of the sacrifice zone mentality, whether it applies to peoples or to places.