This essay looks back upon China’s LGBTQ culture around the 2008 Summer Olympics to reflect upon its contemporary gender and sexual politics around the 2022 Winter Olympics.

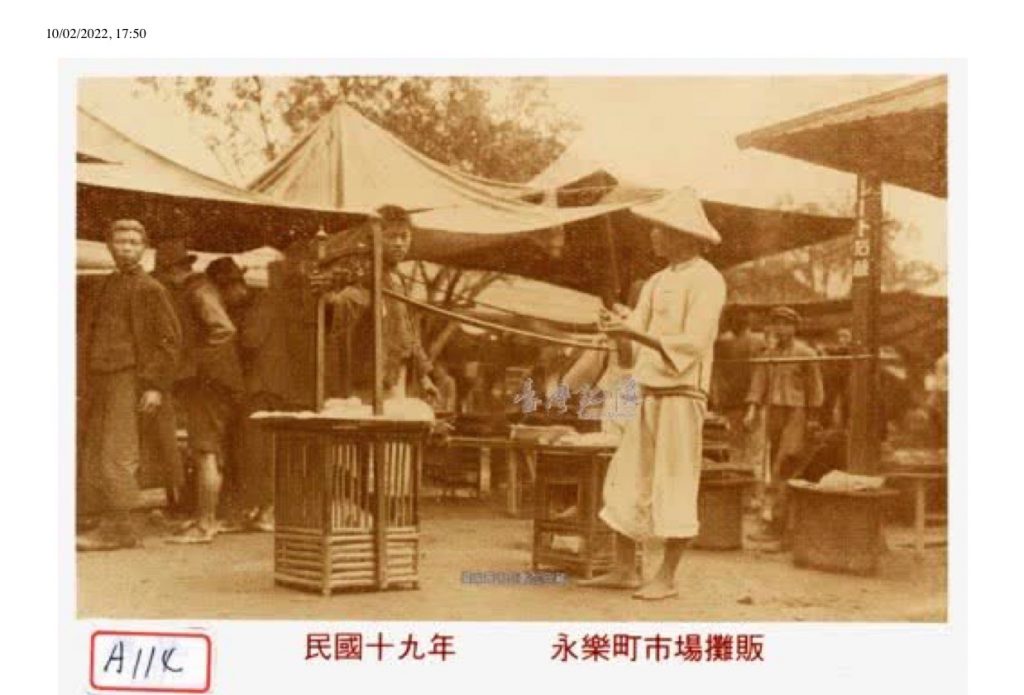

On 14 February 2009, on the newly renovated Qianmen Street near Tiananmen in central Beijing, a ‘same-sex wedding’ was taking place. A gay couple and a lesbian couple were taking wedding photos in public in front of strangers. The scene attracted the attention of many curious passers-by. Some volunteers distributed flowers to the onlookers and wished them a happy Valentine’s Day. A small film crew followed the photo shoots and also interviewed the passers-by about their attitudes toward LGBTQ people and same-sex marriage. Although some interviewees expressed concern or even objection to the idea of same-sex marriage, most people interviewed seemed supportive of LGBTQ people and their rights. The atmosphere was relaxed and the conversations were good-humored. There were security guards standing nearby but no police intervention occurred. The event was later covered by national and international media including China Daily, China’s official English-language newspaper.[1] The Guangzhou-based Southern Metropolitan Weekly reported the event with an eye-catching news headline: ‘Same-Sex Wedding in Beijing: From Underground to the Street’ highlighting the historical significance of the event.

It was later revealed that the scene mentioned above was a piece of performance art in the ‘flash mob’ form of activism organized by Tongyu (‘Common Language’), a queer organization based in Beijing. This has been considered a milestone event in China’s LGBTQ history, epitomizing a glocalized form of queer activism that is flexible, contingent, culturally sensitive and that does not have to follow the Western LGBTQ Pride paradigm.[2] The documentary that recorded the event, New Beijing, New Marriage, co-directed by Fan Popo and David Zheng, also became a landmark film in Chinese queer cinema, exemplifying a performative mode of documentary, what I call the ‘theatre documentary convergence’.[3] More importantly, the film captured the optimism and creative energy within China’s LGBTQ communities in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The film’s reference to the Olympics could not have been clearer: the film title New Beijing, New Marriage was a tongue-in-cheek parody of the 2008 Olympics slogan ‘New Beijing, New Olympics’. The filmmakers also asked in the film synopsis: did the freshly branded ‘New Beijing’ also bring about ‘new concepts’ about love and marriage?[4]

There are positive and negative things to be said about the 2008 historical juncture. In hindsight, it was an era marked by openness and an undogmatic way of doing things. Having successfully joined the World Trade Organization and escaped the global financial crisis, China was eager to show to the world an open image, and the Olympic Games became a good way for such a showcase. For many LGBTQ people, it was a time full of hope and optimism. Although not legally recognized by the Chinese government, LGBTQ people were nonetheless able to set up grassroots organizations and conduct rights-based activism, often under the disguise of HIV/AIDS intervention or women’s rights. In 2008 alone, some key community organizations with national impacts were established, including the Beijing LGBT Centre, China Independent Queer Film Tour, PFLAG (Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) China, and Chinese Lala/Lesbian Alliance. In the same year, the community zine Friend celebrated its tenth anniversary, and Cui Zi’en’s documentary about queer community history, Queer China, ‘Comrade’ China, was completed. I attended the film’s premiere in Songzhuang, an artist and filmmaker’s community near Beijing, in November 2008. No one said doing things was easy back then: queer filmmakers and activists had to constantly negotiate with often idiosyncratic political control and media censorship. But it was still possible to do things, and there seemed endless possibilities and creative energy at the time.

Fourteen years later, in 2022, we are living in a different world, not least because of the raging COVID-19 pandemic and the escalating war in Europe. Meanwhile, Beijing held another Olympics, a Winter Olympics of a smaller scale in comparison to the 2008 Summer Olympics. The glamour and ambition of the 2008 Olympics was heavily reduced this time, in the context of the pandemic and also because of several countries’ diplomatic boycotts. Even with all the controversies surrounding these Winter Olympics, Beijing promised to impress the world with its stringent quarantine measures, excellent athletic performance, as well as the power and determination to get difficult things done.

Unlike in 2008, however, today we cannot hear the open expression of LGBTQ voices in China, and it is difficult to know what—if anything—is going on in China’s LGBTQ communities. This is hardly surprising, given China’s frequent crackdown on LGBTQ rights in the last few years: in 2020, China’s longest running LGBTQ public event, Shanghai Pride, was forced to shut down.[5] In 2021, dozens of social media accounts run by LGBTQ university students were blocked and deleted without warning.[6] The few remaining LGBTQ organizations—if they are allowed to exist at all—have to keep a low profile. The ‘same-sex wedding’ event that took place in Qianmen in 2009 would no longer be imaginable in today’s Beijing. What was thought of as the beginning of Chinese queer activism back then had turned out to be a peak. At a time when limited spaces for LGBTQ culture have fast been shrinking, the 2008 historical juncture seemed a nostalgic ‘golden era’ for many queer activists.

Today we see the relentless rise of a patriarchal and heteronormative culture in mainstream media and in Chinese society. Its zeitgeist is embodied by the hard, macho-type of ‘wolf warrior’ masculinity in the Chinese blockbuster Wolf Warrior 2.[7] Soft masculinity and gender androgyny, which used to be valorized in East Asian contexts, has been designated a social problem. In early 2021, China’s Ministry of Education called on schools to reform their physical education curriculum in a proposal titled ‘The Proposal to Prevent the Feminization of Male Adolescents’.[8] In late 2021, China’s media regulator issued a ban on ‘effeminate men’—derogatorily referred to as niangpao (‘sissy pants’) in the official document—on TV and video streaming sites.[9] Meanwhile, women have constantly been called on to go back home, get married, to be good housewives and mothers, and to give birth to more children.[10] #Metoo has been banned and feminist activists have been detained or put under strict surveillance.[11] Late in 2021, after having accused a retired, high-ranking Chinese government official of sexual harassment, Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai disappeared from public view for a while; her safety remained a public concern after her staged reappearance.>[12] Even during the 2022 Winter Olympics, news about the trafficking of women in eastern China’s Jiangsu Province surfaced—and then quickly was censored—on Chinese social media.[13] What we are witnessing, in other words, is the resurgence of a conservative and patriarchal gender ideology advocated by the state and endorsed by mainstream media. This ideology is often imbued with a strong nationalistic undertone: there seems a clear demarcation of what is considered Chinese and what is considered Western, regardless of the inaccuracy of these claims vis-à-vis the long history of gender variance and sexual diversity in China, as well as the messy entanglements of gender discourses and activist cultures globally.

These conservative state policies and media discourses have real-life consequences. In December 2021, Zhou Peng, a 26-year-old young man from Zhejiang province, was found dead. His note suggested that he might have committed suicide because he was bullied for being ‘too effeminate’.[14] Although the case was quickly dismissed by the police, it raised serious concerns in Chinese cyberspace. Many people came to the realization that this tragedy could happen to anyone who does not—or is not willing to—fit into the newly-enforced gender, sexual and social norms. Something like Zhou Peng’s death was not unexpected in a society where hegemonic masculinity is valorized, ‘masculinity education’ increasingly is becoming a norm, and LGBTQ groups and social media accounts are routinely shut down. Zhou Peng’s death is not the first and may not be the last of such gender related tragedies, and it reminds people of the human cost of the state-led conservative, masculinist, and heteronormative gender discourses.

The valorization of masculinity, as well as the endorsement of conservative gender norms, is the result of an increasingly macho and aggressive Chinese politics. Situated in dramatic tension within global geopolitics, China is flexing its muscles to the world by ‘toughening up’ its national and international image and by conducting a ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’.[15] In the 2022 Olympics, we witnessed Chinese athletes achieve plenty of gold medals, and Beijing has shown off its political and economic power through extravagant opening and closing ceremonies (even if in empty stadiums). But is China strong and determined and confident enough to offer sufficient space and freedom for men, women, trans and queer people who do not fit state-mandated gender norms? It seems that, for the moment, gender and sexual minorities in China are perceived as so threatening that there may not yet be a place for them in the country’s grand ‘Chinese dream’ and ‘shared future’.[16]

NOTES

[1] China Daily: http://www.china.org.cn/living_in_china/news/2009-04/16/content_17615339.htm

[2] a milestone event: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9781003027898-9/new-beijing-new-marriage-hongwei-bao

[3] theatre documentary convergence https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-handbook-of-global-sexualities/i6278.xml

[4] New Beijing, New Marriage: https://www.cultureunplugged.com/documentary/watch-online/play/54331/New-Beijing–New-Marriage——————

[5] Shanghai Pride: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/08/14/asia/shanghai-pride-shutdown-intl-hnk/index.html

[6] LGBTQ social media accounts: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/08/outrage-over-crackdown-on-lgbtq-wechat-accounts-in-china

[7] Wolf Warrior: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/2018/02/22/wolf-warrior-ii-the-rise-of-china-and-gendersexuality-politics/

[8] The Proposal to Prevent the Feminisation of Male Adolescents: https://radiichina.com/masculine-feminization-teenagers/

[9] niangpao: https://www.vice.com/en/article/xgx3nn/china-masculinity-sissy-stars

[10] more children: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/31/world/asia/china-three-child-policy.html

[11] feminist activists: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/apr/17/chinas-feminist-five-this-is-the-worst-crackdown-on-lawyers-activists-and-scholars-in-decades

[12] Peng Shuai: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-59376438

[13] trafficking of women: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1009739/investigators-release-trafficking-details-of-woman-chained-to-wall-

[14] Zhou Peng: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-59576108

[15] wolf warrior diplomacy: https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/interpreting-chinas-wolf-warrior-diplomacy/

[16] Chinese dream: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-22726375 Shared future: https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/together-shared-future-unveiled-motto-beijing-2022-games-2021-09-17/