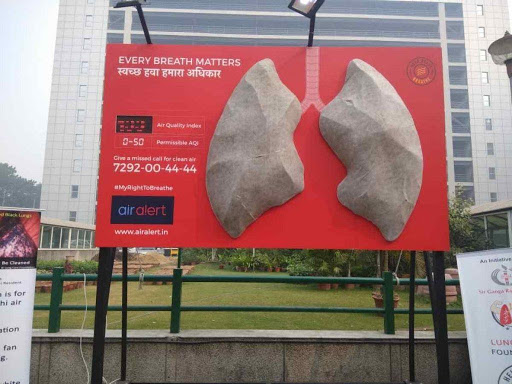

In November 2018, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital (SGRH), one of Delhi’s premier private hospitals, installed a giant replica of human lungs on a full-size billboard outside its entrance. The installation was designed to change color over time based on the quantity of air pollution the “inhalators” pulled through the porous, HEPA-filter-wrapped white exterior. An LED display of the real-time air quality index (AQI) beside the “lungs” flashed levels in the “hazardous” range (≥400).

This was north India’s third consecutive year of what activists term airpocalypse, an extreme air pollution event in the cooling late-autumn months when citywide mortality numbers rise alongside the AQI. The Indian Medical Association had declared a state of medical emergency in Delhi days before the lung installation appeared. Respiratory departments across the city saw patients line up by the hundreds, suffering from asthma attacks and irrepressible coughing.

While the clinical rooms inside SGRH provide high-end imaging analysis of individual pulmonary systems, the giant lung display outside offered a different type of imaging test. Rather than diagnosing the effects of a season or lifetime of breathing dirty air, the installation was a singular pulmonary apparatus standing in for the aggregate lung of the nation. The accumulation of particulate matter was meant to signal the accumulation of collective harm. Visualizing Indian pulmonary vulnerability, these “lungs” turned black in a mere five days, proving an effective, if obvious, object lesson in respiratory ailment.

An SGRH doctor explained the installation’s aim: “to prove the hazardous impact of Delhi’s air pollution.” If this were all that was at stake, the event would have passed unnoticed, one among many public awareness exercises admonishing residents to reduce strenuous activity on high-pollution days or stop bursting firecrackers during Diwali celebrations. However, the lung display—circulating widely in the media and popular conversation—gathered greater semiotic power through the implicit biopolitical claim it proffered: Indian lungs are the same as other human lungs, vulnerable to atmospheric pollution. As an anthropo-metrical device depicting Indian vulnerability to death-dealing airs, it announced: “we too belong to the Anthropos of the Anthropocene.” Expanding private car use, burning coal to develop industry, and throwing thousands of tons of harmful particulate matter into the lower atmosphere might be the government’s path to establishing India’s global standing—what is often glossed as India rising. The lung display flashed a warning that this path to one type of standing comes at the expense of a different one.

~~~~

In January 2014, the World Health Organization ranked Delhi as the most air-polluted city in the world. Based on the WHO’s Global Burden of Disease project, which uses globally benchmarked epidemiological models to explain the relationship between pollution inhalation and lung disease, scientists in India and abroad followed suit with widely reported estimates of mass atmospheric death: 1.24 million premature air pollution-induced deaths occurred across India in 2017 alone, found a major study published in The Lancet; Delhiites on average lose more than ten years of life due to bad air, pronounced the University of Chicago’s Air Quality Life Index.

These findings were mobilized by environmental activists through a flurry of anti-pollution legal petitions in the Supreme Court and National Green Tribunal, prompting the courts’ rollout of a ban on pre-Diwali firework sales, new regulations on construction dust, and a plan to remove old cars and trucks from the city. Key ministries in the Government of India responded differently, opposing such strict emissions controls and rejecting these death statistics as just another iteration of imperial science throwing shade on the (post-)colony. The Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC), for example, declared that “these numbers are not validated for Indian conditions,” insisting that “international studies should not be cited as reference.” The move to deflect the imperial stigmata of global health—evident in the global “ranking” of all but two of the world’s twenty most-polluted cities in South Asia—however, rested on its own presumption of “natural” civilizational hierarchy.

The environment minister, for example, stated in parliament that “medical history, immunity, and heredity of the individuals” falling ill must be considered when assessing the morbidity effects of pollution. The Ministry of Heavy Industries, in oral testimony challenging the National Green Tribunal’s ban on diesel vehicles more than ten-years-old, suggested that “fine dust” cannot be presumed to harm the Indian lung in the same way as it harms the European lung because of its natural occurrence on the subcontinent. Reintroducing the colonial specter of tropical difference and the inherently polluted Indo-Gangetic plains, the member of parliament representing the New Delhi constituency disputed the need for action to curb air pollution, remarking that “Delhi smog is a natural phenomenon, happening due to Delhi’s geography, and there are places with worse air than Delhi.” The MoEFCC secretary in January 2019 went so far as to claim that “we have no data linking air pollution with death” in India.

Governmental claims of Indian immunity to atmospheric pollution draw from a longer colonial legacy of racialized medicine. Consider, for example, Colonel Kenneth MacLeod’s remarks at the opening of the Section of Tropical Disease at the British Medical Association in 1900. Describing typhoid and “dust colic”—a disease caused by “the swallowing with water and food of irritating dust particles of grit blow by the dust storms”—MacLeod argued that “the native immunity in India, though not absolute, is undoubted.” F.G. Clemow’s 1903 Geography of Disease explained the neo-Lamarckian premises underpinning this theory of racial immunity, positing that certain germs or poisons might become “not merely an individual immunity, but a racial immunity, transmissible from generation to generation, and truly permanent so long as man shall continue to live in an atmosphere of these particular organisms.” Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century understandings of Indian immunity to dust and atmospheric pollution intersected with global interest in the comparative study of racial “traits.” The lung, it turns out, provided a perfect organ for the production of a system of hierarchical comparison, with pulmonary science dedicated to measuring and classifying lung size based on race.

The hypothesis positing non-white pulmonary difference vis-à-vis white lungs was espoused far earlier in a different colonial setting. Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, written in 1785, first introduced the language of “difference of structure in the pulmonary apparatus.” In the context of the Southern plantation economy of which he was a part, Jefferson argued that black people were especially suited to agricultural labor due to their greater tolerance of heat compared with Europeans. Lung size, it was suggested, was inversely related to the capacity of the body to dissipate heat. Small lungs were suited to tropical conditions. As Lundy Braun documents in her important book on racialized lung science, nearly a century passed before the plantation physician Samuel Cartwright tested Jefferson’s interpretive framework. Building on the newly formalized techniques of spirometry used for quantifying what came to be called “vital capacity”—measured typically as the maximum volume of air one can exhale in a single breath—he found that “the deficiency in the negro” was “20 per cent.” Defining difference as “deficiency,” Cartwright, Braun argues, “established race as a key organizing principle of lung function measurements.”

While serving as a visiting professor in 1921 at Peking Union Medical College, established by the Rockefeller Foundation, the Harvard physician-scientist Francis Peabody delivered a lecture on the “Clinical Importance of the Vital Capacity of the Lungs” to a mostly North American audience, among whom was US physician John Foster, then based at the Hunan-Yale Hospital. Two years later, Foster published the findings from the first systematic study of vital capacity among “the Eastern Races” with his Chinese collaborator P. L. Hsieh, using Peabody’s “normal standards” for “American” lungs as the benchmark. Globally comparative race-based studies of lung function would soon follow, introducing into pulmonary medicine what May Wilson and Dayton Edwards in 1922 called “a possible racial factor.”

The image above, depicting the 1921 dedication ceremony at Peking Union Medical College, shows this US–East Asia circuitry of racializing lung science. Francis Peabody appears to be on the far left of the photograph, beside someone with the likeness of John Foster. This group of mostly men might be understood to have been carrying out foundational “area studies” work, enclosing functional differences in lung capacity into the geo-racial categories of “America,” “East,” and “China,” with individual scientists helping produce “normal” vital capacity numbers for each of these respective areas. Foster and Hsieh’s 1923 paper cites Peabody’s methods in its first sentence, and the paper offers a single-line conclusion: “The Chinese show much lower vital capacity ratios than Westerners.” Reifying anatomical difference as a meaningful foundation of racial formation and vitality, race-comparative spirometric measures of vital capacity would become foundational to pulmonary medicine: you cannot breathe into a spirometer today without a clinician already marking your race. Vital capacity, as an anthropo-metric, is necessarily raced.

The first study bringing “India” into the citationary structure of comparative lung studies, published in The Indian Medical Gazette in 1929 by S. L. Bhatia, Dean of Grant Medical College, Bombay, cited Wilson and Edwards as inspiration. Testing the “existence of a possible racial factor” (Wilson and Edwards’s exact language), Bhatia replicated Foster and Hsieh’s methods on one hundred Indian subjects and concluded that “the vital capacity of the lungs of this group of 100 Indians is much smaller than normal standards given for Western people”: between ten and thirty percent smaller, he estimated. In the only table presented in his paper, Bhatia reproduced Foster and Hsieh’s standards for Chinese men, as well as their published numbers (drawn from Peabody) for “American” lung function as the benchmark against which Indian deficiency could be gauged. This marked a moment of global diffusion of spirometric norms in which whiteness became an assumed standard. Race-based anatomical difference, in turn, mapped onto immunological difference, with vital capacity operating as an anthropo-metric to demonstrate functional difference across race/area. Small lungs confirmed Indians’ racial adaptation to tropical air. Atmospheric difference produced areas of (and area as) biological difference.

While this “area studies” work was not an explicitly stated civilizational project—given the clinical need to have lung-function baselines for determining when a subject was suffering from reduced vital capacity (= ill) and not simply born into an ethnic group “endowed” with smaller lungs (= not-ill)—it did put into play an economy of commensurability allowing biological difference to be compared and judged. This is evident in the growth of a global industry of comparative spirometric studies into the mid-twentieth century that pursued racially differentiated benchmarks for vital capacity and that focused narrowly on anthropometric and genetic underpinnings, with virtually no mention of environmental or dietary factors that might contribute to variation in vital capacity. J. E. Cotes’s popular 1965 handbook Lung Function is indicative of this framing:

In general the vital capacities of people of European descent appear to be larger than those of other ethnic groups; of these, the inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent and the people of Polynesian stock appear to have the smallest volumes with the Negroid and Mongoloid peoples intermediate (356).

These findings were reproduced in updated studies in the 1970s and have held into the present. The most recent sixth edition of Lung Function, published in 2009, uses less racialized language, but its findings have barely changed, stating that across India “the levels of lung function… are systematically lower than in Caucasians (16-28% lower).” The reference paper most cited in media and judicial discussions of Indian vital capacity today, published in The Lancet in 2013, observes that “compared with North America or Europe, FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in one second; a standard measure of vital capacity] adjusted for height, age, and sex was 31.3% lower in south Asia.”

~~~

In the face of the facticity of Indian pulmonary difference, the problem of area posed so astutely in the February 2019 issue of positions by Gavin Walker and Naoki Sakai as the enclosure of difference into interiority takes on an elemental, biophysical urgency. The colonial medical thought that affirmed the mutually constituted uniqueness of European vulnerability, on one hand, and Indian resistance to (sub-)tropical air, on the other, had the effect of pushing native populations away from a livable life. The state biomedical reasoning that obstructs pollution abatement action today must be seen as enforcing this same colonial model of necropolitics: making die through atmospheric abandonment. By opposing car restrictions and related emissions controls in the name of a presumed native immunity to pollution, the Indian state is not subjecting Indian soldiers to unshielded heat or “miasmas,” as the colonial state did. It is rather submitting the entire population to slow death by breath. The SGRH lung installation’s surprising semiotic resonance—who would normally care about a hospital’s anatomical display?—thus marks a counter-visuality opposing the reduction of popular suffering to meaninglessness. It operated as a critical area studies apparatus of sorts, affirming Indian biological parity with the universal subject of global health and challenging the extension of racializing pulmonary medicine into the necropolitical project of the late-industrial state.