As someone who grew up in Shenzhen in the 1980s-1990s and has lived in the US since 2000, I’ve come to see returning to the Special Economic Zone today as a journey “back to the future.” During my last trip there, I walked down the “memory lane” of Huaqiangbei (Huaqiang North Road, or HQB), the place once known for Shanzhai (or “knockoff”) cell phones back in the early 2000s but that was re-branded around 2015 as China’s “No. 1 Electronics Street.” To many, HQB emblematizes the city’s 40-year history borne of China’s post-1978 Reform and Opening Up. As I found my way there just after the Chinese New Year in 2025, the comingled notion of time – simultaneously captured in the “back to” and “the future” – was precisely what I experienced.

It was one of those warm winter afternoons in southern China, now designated as the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA). I took the East Rail Line from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) (where I had been a visiting scholar) with an old friend from Shenzhen, a CUHK alumna who now works at Amazon Web Services in Hong Kong. We were going to Shenzhen to have dinner with friends from our elementary and high schools. Arriving at Lok Ma Chau, we joined the crowd heading “up” – what the Hong Kong locals would say, referring to the geographical movement up north to the mainland. Back when I first arrived in Shenzhen in 1986, visiting Hong Kong (or even purchasing goods from there at duty-free stores in the city) was an encounter with the more modern, the more advanced, the more “developed” world – “the future.” These days, however, more people regularly travel from Hong Kong (including Hong Kong natives and residents originally from mainland) to Shenzhen for leisure, entertainment, and consumption in general. As friends in Hong Kong have repeatedly told me, everything is “half-price” once you cross the border, and the service is better and choices more abundant. Many have opted to live in Shenzhen and commute to Hong Kong to cut the costs of living, hailing the GBA into everyday being.

At the Futian customs, we helped two Korean youths who spoke some Chinese with translation; they had to turn back and get their 10-day visa-free entry – newly installed by the central government to attract foreign tourists – at another checkpoint in Huanggang instead of the one at Futian. After getting through the busy customs fairly quickly, we arrived at the Shenzhen metro right at the exit. I helped my friend reconfigure her Hong Kong Alipay to take the metro and a few stops later, we arrived at the Shenzhen Civic Center. We stopped at Gaga (Gaga 鲜语, with no relation to Lady Gaga, to my knowledge). With over 20 branches in the city and a dozen more elsewhere, this woman-owned Shenzhen chain inspired by street cafés in Europe was established in 2010 and had become my go-to spot for salads, previously hard to find in China. Offering a wide variety of light fare, elegant décor, and a come-at-any-time atmosphere, Gaga has a bold mission – “to provide high-quality lifestyle solutions for China’s 400 million middle-class people.”

Fueled by my Sangria-inspired fusion tea made with fresh fruits, I decided to pay a visit to HQB before dinner time. Friends had warned me that the stores might not be open, as most migrant workers in Shenzhen typically return to their hometowns located elsewhere in China during the New Year period. But I decided to try my luck. When I arrived at the Northern end of the HQB road, I recalled that back in 2015 the street was still a site for the construction of the subway before it was transformed into a pedestrian street in 2017. Upon exiting the HQB station, the first thing that caught my attention was the busy DJI (大疆) store at Manha Electronics Plaza, packed with customers checking out the newest line of products released by the world’s leading manufacturer for consumer drones. A friend working as a partner at the law firm representing DJI had recently told me that the company also acquired Hasselblad, the premium brand-name camera maker from Sweden, in 2023. With the slogan “The Future of Possible,” the Shenzhen company founded by the Hangzhou native Wang Tao, who got his degree in Hong Kong, is now the symbol of the so-called “low-altitude economy” being promoted since 2024, highlighting drones and electric Vertical Take-off and Landing aircrafts (or eVTOLs) as its “new-quality productive force” (新质生产力). Sure enough, right outside the DJI store were rows of festively decorated stands with signs proclaiming “Huaqiangbei New-Quality Happy New Year” and slogans promoting a “state subsidy” supporting upgrades of electronics and appliances. In the economic downturn that was seemingly on the minds of just about everyone I had met in the past two months, attempts like this to stimulate domestic consumption can come as no surprise.

I then came upon one of the Steinway pianos stationed on the roadside for anyone interested in playing. When a little girl traveling with her dad finished her song, I took my turn. Another woman patiently waited to play for her male companion. As I said goodbye to the English tagline on the piano — “I love Huaqiangbei. Play me, I’m Yours” — I remembered that the world-famous pianist, Li Yundi, the youngest to win the International Chopin Piano Competition, originally trained with a Shenzhen-based music teacher. Moments later, I saw one of those “Public Welfare Piano Rooms” where you can book a 30-minute slot via WeChat and practice for free. I have yet to encounter anything like this in the Euro-American cities that I have visited, and would be curious to see if they might appear sometime in the future…

Next to the piano parlor is a vending station called “Robohub” advertising an appetizing Caramel Macchiato. The density of places where one can get coffee or milk tea in Shenzhen has been part of my amazement on this trip. (Intrigued by the ubiquity of Luckin Coffee, a Beijing-originated chain that is now a major rival of Starbucks at least in the number of branches, I tried some of its specialty drinks and understood why several of my friends have come to like it better than Starbucks. Not only does it provide varieties unavailable at Starbucks at a fraction of the latter’s price, like many other stores it’s 100% integrated with AliPay and WeChat Pay, allowing customers to locate branches and pick up orders super-fast and on the go.)

Not far from the piano room and the Robohub were some delivery workers in Meituan yellow vests and helmets resting on their e-bikes, waiting for orders. Part of living in China’s highly efficient platform economy entails at once being awed by the speed with which orders can appear at one’s doorstep and lamenting the tremendous pressure that the algorithmic regime exerts on the riders. I was reminded of a film I saw on the plane, 《逆行人生》(Upstream), about a middle-aged computer programmer getting laid off and becoming a delivery worker to support his three-generational family. Directed by the comedian XU Zheng and starring himself and the actress XIN Zhilei (famous for her role in the wildly popular TV show Blossoms Shanghai in 2024), the film has brought the daily struggles of delivery workers – previously a topic of scholarly research and investigative journalism – into cinematic visibility. To me, the film’s apparent effort in injecting a kind of “positive energy” into an economic depression was less interesting than the plot twist that, while clumsy at his new job at the beginning, the programmer later developed an app to help riders navigate the city streets. To help him perfect it, another high-earning rider gifted him a notebook filled with sketches of secret “fast routes” – arguably a subtle tribute to the embodied intelligence of delivery workers, often under-recognized by “knowledge workers” like the programmer.

Soon after, I found myself at the door of the HQB Museum, established in 2020. Upon exiting the elevator on the fifth floor of the “Modern Window Commercial Plaza” – translated from its Chinese name “现代之窗商业广场”) – that houses it, a giagantic lit-up circuit board on one side of the wall immediately caught my attention.

As colorful lights appear on the circuit indicating paths toward different directions, I thought of anthropologist Max Hirsh’s point that special border zones like Shenzhen tend to orient themselves spatially around infrastructures of mobility. The circuit wall immediately brought to mind this heightened attention to infrastructural linkages, given HBQ’s status as a key node in the global network of digital production. The more recent GBA (Greater Bay Area) discourse has also emphasized fast-improving connectivity via railways, highways, ports, bridges, and tunnels between Shenzhen – the “core engine” – and another eight Southern cities along with the special regions of Hong Kong and Macao.

If the circuit wall resembled a map, its adjacent ceiling, also lit with bright lights, was more reminiscent of a Computer Processing Unit (CPU), with sparkly transistors of various sizes protruding downward. It also looked quite like a city’s urban planning model turned upside down and shown in night mode. On the floor, the reflective black surface with crisscrossing white lines extended this digital “feel” to the three-dimensional space of the entire room – properly named the “Impression Hall.” I was for sure impressed by the apparent attempt to enact “the city as a medium” metaphor discussed by theorists such as Fredrick Kittler. More precisely, it is the “city as a computer” vision that has seemingly informed the design of the museum in ways that also reflect the aspiration of Shenzhen to evolve toward a “smart city” with an even deeper integration of information technologies with the built environment, as may be seen in the use of AI to map out traffic routes for drones.

Just as I sensed that there was something missing, I was drawn to the various panels on the wall opposite to the circuit board, titled “Memories of HQB (我,在华强北)” featuring pictures taken at HQB of workers, pedestrians, politicians, students. The central panel highlights footage ranging from elementary schoolers’ speech contests about Shenzhen’s technological development to construction workers playing the pianos at HQB. I noticed that some of the clips showcasing a worker disassembling a circuit board seemed to have come from another “main melody” (state-sponsored mainstream) film I saw on the plane, 《奇迹·笨小孩》(Nice View), a heart-wrenching worker-turned-entrepreneur story based in HQB, starring youth favorite 易烊千玺 [Jackson Yee]. After much struggle, the main character and the group of “lumpen proletariats” (such as a laid-off worker with hearing impairment and a veteran boxer) that have come to his aid succeed in launching a company specializing in e-waste processing and recycling.

It suddenly dawned on me that what was obscured in the narratives of both the film and the HQB museum was the memory of Shanzhai as a cultural practice. Back in the early 2000s, as communication scholars such as Jack Qiu and Cara Wallis have observed, HQB was full of small shops selling knockoff brand-name electronics, especially cell phones, that boasted features such as low costs, long-lasting battery, striking aesthetics (take “iPhome,” for example), and even subwoofers, that were popular among rural-to-urban migrant workers. This distinctive manifestation of the globalizing Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Regime has been subsumed in a nation-branding discourse of “From Made in China to Created in China” (从中国制造到中国创造) that seeks to transform Shanzhai culture into economic value.

A similar kind of absorption is arguably at work at the HQB museum. As I followed the moving images to “enter the past” through a “Time Corridor,” I walked through four rooms, dedicated to Dream of Development, Dream of Entrepreneurship, Dream of Innovation, and Dream of the Future (发展梦, 创业梦, 创新梦,未来梦), respectively. In the “Entrepreneurship” room, I saw a family posing for pictures in front of a mock HQB stall from the Shanzhai era, with a sign above saying “Store of a Future Billionaire” and a variety of phones that would have been characterized as Shanzhai phones displayed in the counter below. Just like in Nice View, there was a nod to HQB’s Shanzhai past, but the emphasis was without a doubt placed on the future prospect of entrepreneurship.

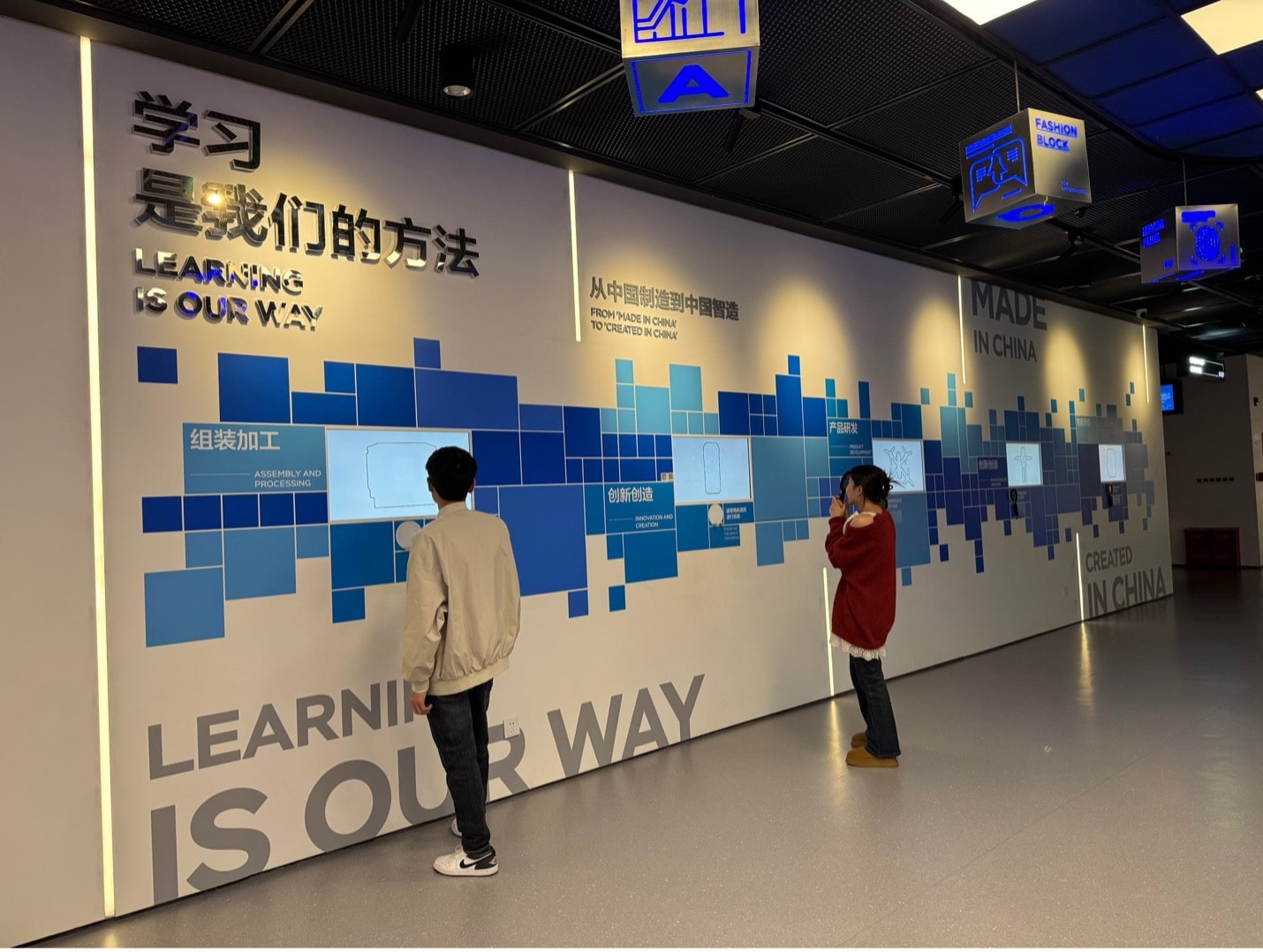

It was in the “Innovation Dream” section that I came upon “From Made in China to Created in China” again, though the Chinese for “Created in China” was no longer “中国创造” (“Created in China,” in terms of brands) but “中国智造” (or “Made in China Intelligently”). “Learning is Our Way (学习是我们的方法),” reads another sign on the same wall. Below, families with kids picked up optical lenses through which to view the inner make-up of five objects: a color TV, a mobile phone, a drone, a robot, and a 5G base station, under the labels “Assembly and Processing,” “Innovation and Creation,” “Product Development,” “Innovation and Creation,” (again) and “Intelligent Upgrade.” It was not until I accessed the online exhibition after I’d left the exhibition that I noticed the second label was originally “模仿制造(Imitation and Making),” referencing the Shanzhai phase that was rendered invisible in the physical space.

In many ways, the HQB museum has told the story of HQB – and in turn, Shenzhen – through a linear frame: once a major site for manufacturing and distributing electronics, it later became the birthplace of tech giants like Tencent and Huawei, and has now risen as an innovation hub for drones, robotics, and electric vehicles. It is perhaps understandable that the Shanzhai moment had to be left out, because it was simultaneously a moment of “backward” copycatting and “forward” technological tinkering. Its mixture of different temporalities defies the strict progression characterized by “From Made in China to Made in China Intelligently.”

After browsing through more demonstrations of robots and videos of their creators, I arrived at the restroom which had a similar décor to that of the Impression Hall. The design was even carried into the interior of the ladies’ room, with the wall above the toilet filled with old-school game consoles and the walls next to the sink painted with colorful circuit boards. On my way out, I noticed the Conclusion panel describing a “new historical starting point” for Shenzhen, with the combination of the GBA development and the city’s status as “a pilot demonstration area of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” I picked up a brochure with the tagline, “Link the Future with Memory (用记忆链接未来)” and pondered on what it might mean.

Shannon Mattern reminds us in “A City is Not a Computer” that the computational city metaphor can obscure “the countless other forms of data and sites of intelligence-generation in the city.” Even though the HQB museum has made an attempt to capture the memories of the place, I couldn’t help but wonder about an alternative storyline that does not so readily subscribe to an entrepreneurial future but pays closer attention to the meanings of Shanzhai, its shifting cultural valences, its vast appeal among migrant workers, and its negotiations with the global IPR regime. How might its aesthetics differ from that of the circuit board wall, CPU ceiling, and futuristic bathrooms?

Back on HQB road, before I used my Alipay app to hail an electric taxi to go to my dinner, I saw several fenced-in areas displaying some smart-looking eVTOLs, with signs announcing “low-altitude economy exhibition halls coming soon.” My trip back to “the future,” as it were, will have to continue upon my next return.

Fan YANG is Professor in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). She is Affiliate Faculty at the Asian Studies Program and the PhD Program in Language, Literacy, and Culture. Author of Disorienting Politics: Chimerican Media and Transpacific Entanglements (2024) and Faked in China: Nation Branding, Counterfeit Culture, and Globalization (2016), she is now working on a new book entitled Shenzhen: A Media City of the Global South.

5 Replies to “Fan Yang, Back to the Future: A Walk through Huaqiangbei in 2025”

I loved this sentence: ” I picked up a brochure with the tagline, “Link the Future with Memory (用记忆链接未来)” and pondered on what it might mean.”

Thanks, Tani! It was great to see you at the AAS!

So interesting how the shanzhai is present-yet-absent!

This is wonderful and both amazing and disorienting. Back in the 320 Globalization and Culture days (c. 2008-2019?) I had a hefty unit on Shenzen, was totally fascinated by it as I had to update it regularly. But what you describe may as well be another world. I always felt that if I went to China, Shenzen was the first place I wanted to visit, the top of my lists of “must-see.” Thanks Fan!

Walking through Huaqiangbei in Shenzhen feels like stepping into the beating heart of the global electronics industry. The streets are alive with bright lights, endless stalls, and the hum of innovation. Every corner offers something new — from tiny circuit boards to the latest smartphones. Amid the noise and energy, you can feel the spirit of creativity and technology that defines modern China..