On the morning of July 18, 2024, our phones were suddenly flooded with images of injured students – our campus was under attack. Students protesting the nationwide escalation of police brutality against the quota-reform movement were being met with tear gas and bullets. Soon, locals and students from other private universities rushed to their aid, fighting back the police and Awami League (AL) goons; a mass uprising was unfolding before our eyes. Attempts to suppress the rebellion led to grotesque violence, turning the tide against the 15-year-long regime that would finally topple on August 5, claiming over a thousand lives and leaving some 11,000 injured along the way.[1]

Looking back, walking with my comrades amidst the mayhem alongside thousands of injured but defiant students feels like a surreal fever dream. To this day, it is hard to believe that we survived that war zone unscathed. Private university students must have been either remarkably brave or foolish to join a battle where they had nothing to win and everything to lose, given how few aimed to join the civil service. Their courage compelled us to stand by them and against the brutality of a regime that was quickly spiraling beyond all control.

As an activist and academic writing about gender, class, and social movements for over a decade, I am familiar with the ‘transversal’ nature of contemporary movements (Yuval-Davis, 1997). It is crucial to recognize the fluid nature of the ‘political field’[2] in which these forces battle, capable of pushing these movements from left to right at any time. The road from the ‘Anti-Discrimination Student Movement’ to the July Uprising was no different. These fields are contoured by the uneven distribution of power, capacities, opportunities, and everyday interactions among actors – civil society, donors, parties, the state, and transnational forces – setting limits on ‘legitimate’ ways of doing politics. This essay explores these interactions, addressing the aspirations behind the July Uprising and the inevitable erasures they entailed.

It all began with the demand to cut back on the 56% quotas in the Bangladesh Civil Service (BCS) exams, in particular the 30% reserved for the 1971 war veterans and their descendants, which many saw as a ‘loyalty scheme’ for the AL. Students had been pursuing quota reform since 2013, with the movement gaining momentum in 2018 and reigniting in June 2024. Unable to quell the protests, the High Court eventually ruled in favour of reform in a desperate attempt at appeasement. However, that ‘victory’ came at a hefty price: reserving only 5% for freedom fighters, 1% for indigenous communities, and 1% for third gender people and people with disabilities. Women and minorities were excluded altogether, a concession to the majoritarian sentiments that underlay the movement from the beginning, with many young protestors still spellbound by the neoliberal illusion of ‘meritocracy.’

To understand how it could all go so far, we must recognise that Bangladesh was established on the principle of liberation from economic deprivation. By the turn of the 20th century, an educated Bengali Muslim middle class had entered the wage economy, whose aspirations and struggle for recognition necessitated a new social contract, ultimately leading to widespread support for the Pakistan movement. Over the next two decades, that support dwindled in the face of what could be called Pakistani ‘internal’ colonialism, giving birth to secular Bengali nationalism as an “antisystemic political programme” and a radical mobilizing tool until the liberation war of 1971, after which it was quickly appropriated to legitimize the new state elite (Van Schendel, 2001). Stagnant industrial development under successive colonial regimes had failed to cultivate a ‘homegrown’ capitalist class, and it was the civil-military-bureaucratic alliance that would dominate the political process in the new nation (Ahmed, 2009). Tertiary education, burgeoning employment opportunities, and social networks within civil-bureaucratic circles enabled a convergence of capitals (Sabur, 2014), paving the way for the Bengali Muslim middle-class to hegemonize the right to articulate the nation, marginalizing those who lacked access to the state (Sabur, 2020). Fifty years later, the quota-reform movement was powered by a similar narrative of deprivation. This was a struggle for recognition by a new aspiring middle class, seeking a new settlement that can only be established on the ruins of the old.

Once again, middle-class aspirations turned to education and the state. Amid skyrocketing inflation and years of ‘jobless growth,’ the BCS offered a lifeline for the thousands of aspiring graduates without the necessary social, cultural, and economic capital, striving to enter a precarious wage economy; the 56% quota system stood in their way. However, this was not the only point of contention. The all-consuming rage of July was also fed by visceral memories of repression, juxtaposed against the selective nationalist history parroted by the AL regime for 15 years. For these students, 1971 was a story in textbooks that they had come to mistrust. One-party rule was all many of them had ever known. They did not witness the 1990 mass uprising that toppled autocratic rule, nor the brief period of functional democracy under the BNP.[3]-AL cycle. However, they did see the co-optation of Shahbag in 2013 and the brutal suppression of the quota reform and road safety movements in 2018. The regime’s ability to get away with sham elections, mass incarceration and extrajudicial killings had rendered it reckless and indifferent to public opinion, gradually eroding the consent of the hegemonic middle class. Sharp divisions within civil society had impaired its ability to keep the state in check. The failure of conventional party politics bred a profound distrust of established power structures/elites, leading to a proliferation of seemingly ‘illiberal’ movements (Bilgrami, 2018; Canovan, 1999; Laclau, 2007; Mudde, 2016) that shaped the consciousness of a generation of students.

By their third term in power, the promise of a ‘Smart Bangladesh’ had grown stale, and a cascade of corruption, money laundering, and embezzlement scandals along with rampant inflation and unemployment had begun to overshadow the dazzle of ‘mega-projects’ like the Padma Bridge, which had long protected the regime’s development narrative. The government’s acquiescence to the new ‘power elite’ proved disastrous. A culture of entitlement replaced ideological politics (Comaroff 2011; Weyland 1999), undermining the political fabric of the party itself. Gone was the tradition of nurturing grassroots leaders through councils; memberships were now offered to family connections or the highest bidder. The systematic annihilation of the opposition and permissiveness towards this oligarchy represented perhaps the most significant missteps of the ‘democratic’ era, breeding political mercenaries ready to align with any cause for the right price and facilitating the rise of majoritarian politics.

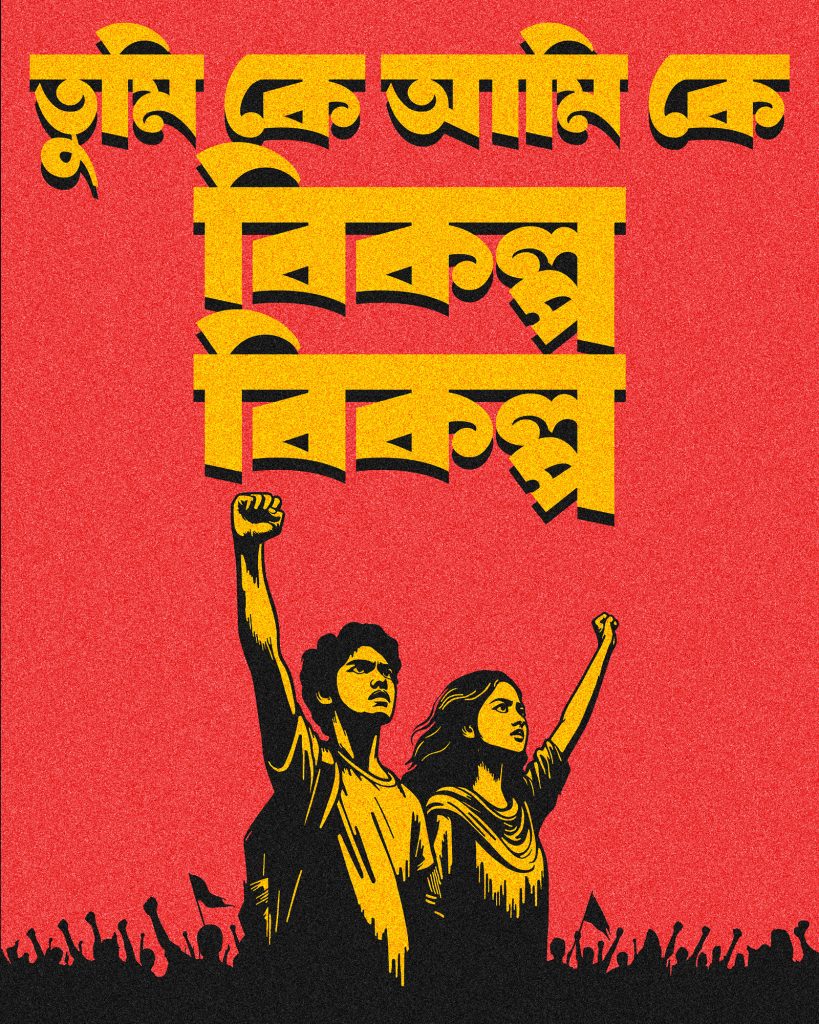

The students leading the charge in July had no place in the promises of ‘nation building’ or ‘development,’ thereby finding allies in others ‘left behind’ by the nation and aspiring to become the ‘alternative’ themselves. The ‘Anti-Discriminatory Students Movement’ aimed to create a platform for collective resistance against the AL regime, fostering a coalition of students with ideologies ranging from left to liberal to extreme right, and with significant participation of women, gender-diverse groups, and indigenous and minority religious communities. However, as the euphoria of ‘victory’ subsided, conflicting narratives of the uprising emerged that began sidelining many of the key protagonists. As the OHCHR report states: “Having been at the forefront of the early protests, women, including protest leaders, were also subjected to arbitrary arrests, torture, ill-treatment, and attacks by security forces and Awami League supporters.” The frontline women coordinators and activists have been systematically excluded from the advisory boards and commissions of the interim government, as well as the post-uprising student leadership. Within a day, the recently launched National Citizens’ Party (NCP) – formed by the leading faction of the student coordinators – caved to online abuse and dropped a gender-diverse member from their leadership committee.

Many female coordinators expressed their despair during a series of dialogues held by Bangladesh Mahila Parishad (BMP). Ipshita[4] from Dhaka University (DU) asked, “Where are our women after the movement? They were left behind in the media after the movement succeeded.” Shithi (DU) echoed similar sentiments: “Traditionally, women have been used as showpieces in major political parties […] No one provided space for us; we had to fight for it even during the movement.” Oishhorjo (DU) and Prarthona (Brac University) recalled the ‘protective’ attitudes of their male counterparts and how they were often made to work under senior male members. Along with bullets and arrest, these women also faced slut-shaming and rape-threats both during and after the movement. Alma from Jahangirnagar University said, “Coming from a conservative family, joining politics was difficult for many of us. We deserve credit. This cannot be the revolution we fought for.”

The July Uprising failed to uphold its spirit of ‘inclusivity’ within a week of toppling the government. Reports of retaliatory killings, looting, and the destruction of minority property and places of worship (including Sufi shrines) were often dismissed as ‘propaganda.’ The OHCHR report has documented the targeting of AL officials and supporters, as well as police and media, as the regime began to crumble. Hindus, Ahmadiyya Muslims, and indigenous people from the Chittagong Hill Tracts were also subjected to human rights abuses. While around 100 arrests have reportedly been made, acts of violent revenge and destruction are continuing with impunity. Indigenous students demanding constitutional recognition as ‘indigenous’ were openly attacked by Muslim majoritarian men with tacit police support. By failing to safeguard its religious and ethnic minority citizens, the state has de facto excluded them from a place in ‘Bangladesh 2.0.’

Euphoria and despair are inevitable aspects of any mass movement (Chowdhury, 2019), but we must also address how the dialectic of aspiration and marginalisation is realigning the political landscape. The political landscape of Bangladesh has never been stable, nor has the relationship between the state and civil society. Women’s organisations and civil society groups had wholeheartedly joined the post-war reconstruction effort, which had taken a socialist direction despite the disapproval of Western donors (Hossain, 2025). That nation-building alliance ended with the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975, initiating the era of military-backed autocratic rule. The successive regimes of Generals Ziaur Rahman and Hussain Muhammad Ershad – beholden to US-Saudi diplomatic ties – oversaw rapid denationalisation and economic/trade liberalisation whilst fostering a new entrepreneurial class, the privatisation of industries, the mushrooming of NGOs, and the declaration of Islam as the state religion (Sabur, 2021). Both regimes selectively adopted progressive policies to preserve donor confidence, advocating for ‘Women in Development’ (WID) while simultaneously pandering to Islamists for legitimacy. The first decade of democracy lifted Bangladesh out of the aid trap; by the 2000s, the country was a poster child for human development, admired by donors instead of being at their mercy (Hossain, 2025).

Each reconfiguration in the political landscape prompted civil society to prioritize different survival strategies, growing less militant with the transition to democracy in a manner closely resembling the situation in Pakistan (Zia, 2009). The rapid growth of a globalized Muslim majoritarianism, continued pandering to Islamists by successive regimes, and the return to power of the ‘secular’ nationalist Awami League in 2008 muddied the waters even further (Sabur, 2025). Since then, civil society’s complex allegiance to and dependence on the state empowered the latter to fight its battles against ‘uncivil society’ on its behalf. The AL regime deployed Islamophobia as a scare tactic to stifle dissent while simultaneously rewarding Islamists and building thousands of mosques; neither could save them in the end. The depoliticisation of the party and the politicization of civil society entirely upended the political field. The interim government reflects this disturbance, peopled with ‘NGO-sourced’ advisors ill-equipped to handle pressure from above or below. Meanwhile, the inexperienced and ideologically discordant student leadership appears increasingly keen to appease reactionary forces for their own survival, ignoring the alarming rise in crowd vigilantism and sexual violence, which has prompted women to organize themselves and take to the streets again as we speak. A thousand lives is a steep price to pay for the reign of ‘might is right.’ After 54 years of bloodletting and plunder, the people of Bangladesh deserve the chance to rest, to have the bare minimum that they have repeatedly fought for – a functional democracy, fundamental civil rights, freedom from foreign interference, and a state that delivers at least as much as it takes, if not more.

Seuty Sabur (PhD) is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the Department of Economics and Social Sciences, School of Humanities and Social Sciences at BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Her core research interest has been the Metropolitan Middle Class of Bangladesh – their lifestyle, changing gender role and their social and transnational networks.

Notes:

[1] As per the recently released UN OHCHR Fact-Finding Report: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/ohchr-fact-finding-report-human-rights-violations-and-abuses-related

[2] Bangladesh Nationalist Party, the AL’s chief political rival.

[3] A ‘field’ signifies “a structured, unequal, and socially constructed environment within which organisations are embedded and to which organisations and activists constantly respond,” maneuvering forms of capital to occupy positions within this hierarchical structure (Bourdieu 2002; Ray 1998).

[4] The coordinators’ names have been changed for their protection.

References:

Ahmed, K. (2009). State against the Nation: The Decline of the Muslim League in Pre-Independence Bangladesh, 1947-54. Dhaka, Bangladesh: University Press Limited.

Alam, Shamsul, S. M. 1995. The State, Class Formation, and Development in Bangladesh. Lanham, New York and London: University Press of America.

Bilgrami, A. (2018). “Some Reflections on the Limits of Liberalism Akeel Bilgrami.” Social Scientist 46(7): 3–20.

Bourdieu, P. (2002). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. London: Routledge.

Canovan, M. (1999). “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47: 2–16.

Chowdhury, N. S. (2019). Paradox of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Comaroff, J. (2011). “The End of Neoliberalism? What Is Left of the Left.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 637(1): 141–47.

Hossain, N. (2025). The Aid Lab: Understanding Bangladesh’s Unexpected Sucess. 2nd, Bangl ed. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

Laclau, E. (2007). On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

Mudde, C. (2016). “Europe’s Populist Surge: A Long Time in the Making.” Foreign Affairs 95(6): 25–30.

Ray, R. (1998). “Women’s Movements and Political Fields: A Comparison of Two Indian Cities.” Social Problems 45(1): 21–36.

Sabur, S. (2014). “Marital Mobility in the Bangladeshi Middle Class: Matchmaking Strategies and Transnational Networks.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 37(4): 586–604. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00856401.2014.954757.

———. 2020. “Shahabag to Saidpur: Uneasy Intersections and the Politics of Forgetting.” Südasien-Chronik – South Asia Chronicle 10: 97–122.

———. 2021. “Women’s Rights and Social Movements in Bangladesh: The Changing Political Field.” In Civil Society and Citizenship in India and Bangladesh Edited By, eds. Sarbeswar Sahoo and Paul Chaney. New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd.

———. “Radical within Limits: Women’s Movements, Civil Society, and the Political Field in Bangladesh.” Melbourne Asia Review (12).

Van Schendel, Willem. 2001. “Who Speaks for the Nation? Nationalist Rhetoric and the Challenge of Cultural Pluralism in Bangladesh.” In Identity Politics in Central Asia and the Muslim World: Nations and Labour in the Twentieth Century, eds. Willem Van Schendel and EriK J.Zurcher. London and New York: I.B Tauris Publisher, 107–47.

Weyland, K. (1999). “Neoliberal Populism in Latin America and Eastern Europe Author ( s ): Kurt Weyland Published by : Comparative Politics, Ph . D . Programs in Political Science, City University of New York Stable URL : Http://Www.Jstor.Org/Stable/422236 REFERENCES Linked.” Comparative politics, 31(4): 379–401.

Yuval-Davis, N. (1997). Gender and Nation. London, California, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Zia, Afiya Shehrbano. 2009. “The Reinvention of Feminism in Pakistan.” Feminist Review (91): 29–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4.