Joyce Mao

America’s relationship with China is long and tangled, and despite the single-handed efforts of Donald Trump, this new era of bad feeling should not be seen as entirely novel. The Trump administration’s approach to the PRC was but a recent chapter in the ongoing decline of US-China relations. The new cold war resounds with echoes of the old one, including geopolitical maneuvering and proprietary competition over technological innovations. Trump’s exhortations about the “China virus” and allegations of lab cover-ups in Wuhan cannily demonstrated Americans’ gut willingness to believe the worst of the Chinese state. If the original Cold War was an era marked by feeling, knowing, and the ambiguity of both, this was especially true within US-China relations. The lack of a formal relationship and consistent dialogue from 1949 to the early 1970s created a reality gap, leaving much of the unknown to become the irreconcilable. Despite significant changes after normalization, today’s renewal of tensions also thrives on perceptions – what is known, unknown, or anticipated.

The historical economic dynamic between the two countries can tell us much about the origins and contexts of today’s enmity, which squares with a long pattern of American concern about what China’s economy means for the United States. It also affords key insights into why this new cold war feels simultaneously of-the-moment (Covid-19, the ongoing trade war) and like déjà vu (anti-Asian hate crimes, reflexive anti-communism). More than any other aspect of Sino-American relations, the subject of Chinese development has encapsulated what Americans think they know about a country most of them will never see firsthand. These include characteristics used to romanticize and vilify China for centuries: its geographic vastness, massive population, and “sleeping giant” potential. Together, those expectations formulated a modernization story about the United States assisting an alien, less advanced counterpart via trade and capitalism. Sen. Kenneth Wherry from Nebraska summed up the impulse in 1940, exclaiming, “We shall lift China up and up, ever up, until it is just like Kansas City!”

Since the 1700s, the Chinese economy has occupied an idiosyncratic place within the American imagination. As Gordon Chang has described, China was a formative part of the Revolution and the republic’s founding. Mercantile trade with China figured as a significant share of the new national economy and also an outsize measure of American ideological and financial ambitions. Well into the 20th century prominent religious, business, and military figures continued to regard China as the cradle of US global influence as well the nation’s domestic economic growth. The so-called special relationship between the two countries was a common American narrative. Voices within the US described the bond as specifically anti-colonial, an ideological and emotional connection based on common impulses toward free trade, Christianity, and democracy. Tellingly, the Chinese in the US were not considered part of this kinship; immigrants and native-born alike endured oppression via discriminatory laws and other forms of racialized violence. Rather than running counter to America’s love affair for China, domestic anti-Chinese further evidenced how inequitable and non-pluralistic that infatuation really was.

While its proponents described the Open Door as mutually beneficial, its hoped-for effects were one-sided. Heralded as a vital source of goods, labor, and trade, China was thought of as the place where Americans could realize their personal economic fantasies. On a national level, access to Chinese resources and markets would allow the United States to further its passage into globalized modernity. Meanwhile, benefits for the Chinese were trickle-down at best and framed as a collective experience of democratic capitalism, in contrast to the individualistic aspirations that China would fulfill for Americans.

This story ultimately proved unfounded and irresponsive to a changing global order. With the founding of the PRC, US influence and Americans’ access to the mythical China market were eliminated. Apprehension and a sense of loss replaced those earlier optimistic imaginings. The latter, which was real even if not based in reality, held substantive consequences. Since 1949, US officials and ordinary citizens alike have vilified the PRC as a paper tiger, a threat to Western financial practices, and the manifestation of a totalitarian state’s greed.

The moderate liberals who dominated US foreign policy during first half of the Cold War processed events in China through a lens of capitalist development that continues to influence the way US foreign policy organizes the world. Their brand of internationalism championed global financial networks reinforced by military intervention to counter leftist influence. At the heart of liberal internationalism was a faith in economic “modernization” as anti-communism’s most effective tool. Modernization theory argued that orderly capitalist development, with limited regulation from the state, was the only sustainable path to modern democratic societies. Applied to the Cold War, it made strategic foreign aid a centerpiece of containment policy. Capitalist development projects in both the private and public sectors would theoretically encourage Third World nations to reject left-leaning politics. In turn, the growth of global capitalism would spell the death of global communism.

In the case of China, without bilateral relations and reliable firsthand information, the liberal internationalist strategy was to wait and see. Leading figures like Dean Rusk, McGeorge Bundy, and Eugene Black regarded the PRC as an antagonist that, while dangerous in the short-term, was incapable of long-term success. Keen to know more about Mao’s regime, the White House, State Department, and National Security Council looked to CCP economic policies for concrete clues. Any insights could then shape the US calculus for the entire Pacific region during critical moments of the Cold War.

None other than Walt Rostow, the thinker synonymous with modernization theory, forcefully promoted this approach. Counselor to two presidential administrations, including National Security Advisor from 1966-1969, Rostow was a prominent voice within the foreign policy establishment. Early on he identified China’s economic development as a key conundrum. China was “an enormous challenge to the United States and the Free world,” he wrote in 1954. It was first and foremost a financial puzzle: agrarian, revolutionary, rich in manpower but not industry, a country that remained impervious to Western standards of modernity. Rostow concluded that Communist rule was incapable of remedying the lack of a consumer base or technical expertise. China’s potential, he argued, would never be a serious competitor in the global economy. Any attempt to rapidly industrialize flew in the face of what he described as ingrained cultural patterns that stretched back thousands of years. Therefore, capitalist development and modernity would not come easily to China, if it came at all.

And yet it was imperative that the US pay attention. “Peking’s pretensions to power in Asia and its claim as a model of theory and practice for Asia are unlimited,” Rostow explained. As a non-white nation that had experienced ideological, economic, and military revolution, the PRC’s power lay in influence over developing countries the US needed to align with the West. Here was both peril and opportunity for American interests. Rostow urged his fellow liberal internationalists to be ready for the diplomatic opportunities that would arise when China asserted itself. As US officials came to learn about the catastrophic Great Leap Forward, he appeared to be something of a seer.

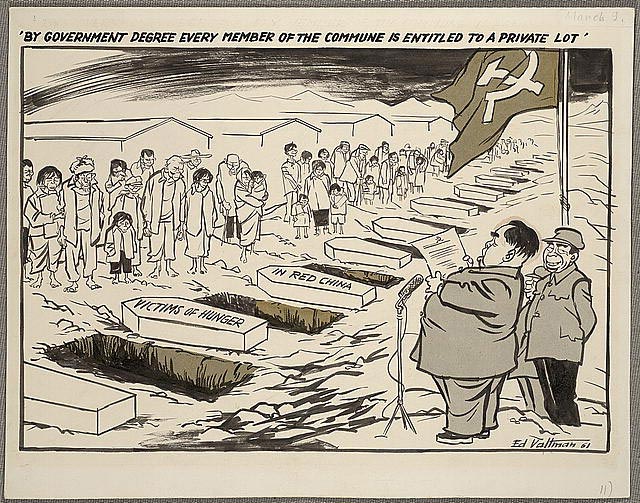

Marked by agricultural disaster and the loss of tens of millions of lives, the Great Leap Forward was a failure for the PRC, wiping out the modest growth of the early 1950s. In one memo, China expert Alfred Jenkins described it as a “fiasco” that “not only set the economy back a decade but nakedly paraded the fallibility of Maoism and of Communism itself.”1 His thoughts reflected the predominant reaction among American officials. They described the Great Leap Forward as the product of inherent Chinese characteristics, namely irrationality and backwardness. The consistency of the language used within government analyses and communications after the Great Leap Forward is striking. It was as if symptoms had finally been observed and a collective diagnosis regarding China’s mental state was possible. Adjectives like “insane,” “sick,” “psychotic,” and “pathological,” were common. The persistent use of scare quotes (“Great Leap Forward”) amplified the characterization of China as psychologically unwell. By questioning the self-description, and even the existence of, China’s attempts to construct a modern economy, US analyses inferred the entire program was a Chinese delusion. Not only was it a subject for mockery, but its very existence as a significant economic endeavor was called into question.

This derision made its way into the public eye via press releases and other statements. In a 1963 speech in San Francisco, Asst. Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Roger Hilsman referred to “the wall of secrecy with which (the Chinese) surround themselves.” He described the “’Great Leap Forward’” as “an attempt to rewrite economics,” replete with “grandiose slogans and frenetic schemes.” It was supposedly proof of how difficult the Chinese were and that they could not be taken seriously. “The Chinese Communists,” Hilsman said, “have set themselves up as a model for the less-developed nations. But, like the king in the fairy tale, they seem unaware that they have no clothes.”2

Such depictions went beyond merely presenting the PRC as a cautionary tale. The Great Leap Forward obviously touched some kind of nerve. The program had audaciously defied established modernization theory, which emphasized development along scalable and predictable, historical lines. Its policies also challenged presumptions of China as a country without an impulse toward modernity. Both offenses had to do with time: US officials still subscribed to the notion of China as ancient and immutable, despite its republican and communist revolutions. The Great Leap Forward, with its emphases on rapid change and self-sufficiency, contradicted US expectations of China as a nation incapable of undertaking industrialization without external intervention. It seemed implausible that China could take so bold an initiative; even the Great Leap Forward’s failures were not enough reassurance. Taken aback, American officials reached again and again for familiar constructions to restore order.

By the mid 1960s, US officials considered China as much a threat as the Soviet Union. Military conflicts like Korea and Vietnam, as well as the PRC’s successful detonation of an atomic bomb in 1964, informed that assessment. However, it was Chinese economic policies that inspired American liberals to re-evaluate the US approach while still retaining presumptions about China’s implausible modernity. In sum, Chinese economic madness justified US intervention. “There has perhaps been more emotion about our China policy than about our policy toward any single country since World War II,” Hilsman told his audience, “yet our nation must look squarely at China, pursuing policies which will protect the interests of our country, of the free world, and of men of good will everywhere.”3

Unlike the conservatives who called in vain for Chiang Kai-shek’s return to the mainland, liberal internationalists actually had the power to craft a proactive China policy. With no formal relationship and an ongoing embargo, direct US intervention was difficult. Washington would have to use other channels to teach the PRC its lesson. The key would be a regional economic and security network composed of ally nations catalyzed by US foreign aid, diplomatic support, and military placement.

Consequently, the US sponsored major initiatives like the Asian Development Bank with the dual motivation of encouraging capitalist modernization and countering Chinese influence. In its subsequent treatment of Asia as a sort of economic laboratory, US policy steadily escalated investments in anti-communism – including multi-lateral diplomacy, foreign aid, and military action – throughout the region. The approach clearly set a precedent for 21st century projects like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. In a 1966 letter to Sen. J. William Fulbright, Walt Rostow wrote: “Our objective in the years ahead should be to help the Asians build a regional structure which could not only deter China from an aggressive, ambitious path but also encourage a more moderate China, addressing itself to enter constructively into Asian Affairs as a major actor.”4 Instead of ignoring the PRC, American liberals were determined to find a way to make it “well and sane.” 5 A pragmatic dose of development internationalism was the antidote for China’s psychosis.

That combination of derision and largesse continues to mark US China policy. Elements of the new cold war, such as conflict in the South China Sea and aggressive trade tariffs, owe much to US policymakers’ residual mindset about what a growing Chinese economy symbolizes for American interests. It is an attitude that continually underestimates China’s capabilities. When those expectations prove wrong, the backlash cuts across partisan, socio-economic, and cultural lines. A recent poll by the Pew Research Center found that a wide swath of voters, not just conservative Republicans, regard the PRC unfavorably. Heightened anxiety about the PRC has historically reflected Americans’ confidence (or lack thereof) in their own governmental institutions, and anti-China rhetoric has proven effective political shorthand for worry about US global status. If popular opinion fuels the politics of foreign relations, the climate of public health crisis, economic hardship, and political uncertainty suggests that the “new” cold war will not be easily resolved at either the grassroots or policy level.

Economic epistemology and its anticipations are intrinsically tied to the calculus of supremacy, but what happens after traditional processes and metrics of progress have been toppled? How will those circumstances shape foreign relations? China’s post-COVID recovery stands in stark contrast to the devastation currently afflicting many First World economies. Given recent contexts, including a new Biden administration, the US-China relationship becomes even more important. In recent remarks Joe Biden has tried to strike a balance, warning China to expect “extreme competition” while also averring that the US does not want conflict. He described Xi Jinping as “very bright” but “without a democratic, small D, bone in his body.” It was a striking echo of liberal Cold War language that remarked upon Chinese leadership’s intellectual capabilities while drawing innate, bodily differences between the two countries. Beyond rhetoric, Biden has signaled he will continue key aspects of his predecessor’s approach, including an emphasis on infrastructure spending and trade protectionism expressly to challenge China. So far, the White House has shown that habits, old and not-so-old alike, tend to die hard.

Joyce Mao is associate professor of history at Middlebury College. Her work focuses on the intersections between American foreign affairs and national politics during the Cold War era, with special attention to US-Asia relations.