Grace En-Yi Ting weaves together Japanese literature, Hong Kong, and Asian American identity in an intellectual and personal narrative of “sideways becoming” through queer/feminist theory.

An earlier version of this essay was presented as an invited talk in May 2021 for the Department of Literature at UC San Diego.

I. Calling out in the night

A queer feminist project of minor intimacies rummages through the everyday, tracing feelings and moments that frequently go unacknowledged in a heteronormative world. Similar to “Public Feelings” projects by queer studies scholars Ann Cvetkovich, Lauren Berlant, José Esteban Muñoz, and others, it is largely a project of “description”—by describing, it gently seeks to initiate change. Questioning the hierarchies through which our variations on love are refracted, it performs resistance to broader structures of violence that seek to dictate how we love in a severely unjust world. It is a protest that is entirely unreasonable in its refusal to quit despite its smallness.

Why should we read with deep feeling and even a sense of wonder as the world falls apart? Many years ago, I started writing a dissertation on “minor intimacies” of Japanese literature with simpler goals: to introduce queer feminist readings of the mundane and its affects to Anglo-American Japanese literary studies, to problematize sexist standards applied to literature written by Japanese women.

In the early stages of the pandemic, I was in my second year of a postdoctoral fellowship at Waseda University in Tokyo; in the summer of 2020, I packed up nine boxes of books, clothing, and household items and moved to Hong Kong to begin a position at the University of Hong Kong. Living through a world in which the most minute aspects of the everyday have been transformed, witnessing anti-Black and anti-Asian racism in the U.S., confronted with unfamiliar racial hierarchies and xenophobia amidst political upheaval in Hong Kong, I find myself returning to my project of queer readings with a renewed sense of urgency.

In Cruising Utopia, queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz critiques the “straight time” of LGBTQ politics adhering to linear narratives of progress that value political expediency and a future defined by adherence to the status quo. He situates his work among feminist and queer of color critiques to describe queerness that is open, indeterminate, built on imagination—“that is extra to the everyday transaction of heteronormative capitalism.”[1] This queerness exists not as identity but as a sort of surplus found in ordinary moments that will “challenge [us] to feel hope and to feel utopia.”[2]

Similarly, in my readings of Japanese literature, I describe the queerness of small connections that form through, around, and despite the oppressiveness of the heteronormative. The queerness of these readings is about overlooked structures of intimacy, imperfect but also sustaining in contexts defined by lack of agency. As one example, my readings of Kawakami Hiromi’s 2001 novel The Briefcase trace delicate connections produced through everyday temporalities, within spaces of loneliness and isolation.

The Briefcase depicts the relationship between a middle-aged woman and her former high school teacher, produced through chance encounters set against the backdrop of the seasons in a quiet Tokyo neighborhood. In the novel, the cyclical movement of the seasons intersects with rhythms of daily rituals involving food and drink. First-person narrator Tsukiko is an office worker frequenting a bar close to her home, where she runs into her now retired high school Japanese teacher, whom she simply calls Sensei, or “Teacher.” For much of the narrative, they “meet” by randomly running into each other at this bar—a neighborhood izakaya—sometimes not seeing each other for weeks, and sometimes seeing each other almost every night. Kawakami gives us the sense that episodes depicted in the text are plucked at random from among meetings so ordinary that many do not bear mention. Many of these encounters take place at night with the intimacy of the two characters framed by their drunkenness in a singular space of night and dreams—not quite separate from the mundane everyday, yet not entirely part of it.

The narrative is simultaneously framed by the larger structure of the seasons, materialized intimately through detailed depictions of seasonal Japanese food that the characters enjoy at the bar. Somewhat idiosyncratic, Tsukiko’s appetite nevertheless aligns well with that of Sensei. At their first chance encounter, she orders three items—natto and tuna, lotus root, pickled scallions—only to hear him mirror her exact order with his. Some time after having a fight, they ignore each other at the bar, but she cannot help noticing the parallel nature of their separate meals: “The boiled tofu came—I nibbled at it at the same pace as Sensei, downed my glass at the same pace as Sensei, and got drunk at the same pace as Sensei.”[3] Their desire for food is matched through tiny details of timing and pacing, enveloped within the larger rhythm of the seasons.

My reading of intimacy and rhythm borrows from work by Henri Lefebvre, a philosopher of the everyday. Through his concept of rhythmanalysis, Lefebvre describes the relationship between cyclical repetition—of the seasons—and linear repetition—of the modern workday. He suggests, “[Rhythm] is neither a substance, nor a matter, nor a thing. Nor is it a simple relation between two or more elements, for example subject and object, or the relative and the absolute…An energy is employed, unfolds in a time and a space (a space-time).”[4] His ideas point to lived, subjective rhythms—dependent upon “preferences, references, and frequencies”—that cannot be easily categorized or contained.[5] While The Briefcase ends with a brief romantic relationship between the two characters, throughout much of the novel, their intimacy exists precisely through such rhythms as something fortuitous, flowing, and undefined.

Both characters are out of sync with more normative temporalities of modern Japanese society. An unmarried woman in her late 30s, Tsukiko leads a starkly solitary life. Going home for the New Year, she and her mother stand next to each other but only wash the dishes in painfully awkward silence, the hollowness of their relationship expressed through this simultaneous closeness and distance. In contrast, Tsukiko and Sensei have the inexplicably right distance between them, a sort of remarkably elegant contradiction. At the bar, they sit comfortably side by side keeping a set distance—not facing each other, not as lovers, but not entirely separate either. They are neither together nor apart. There is a gap between them, but it does not need to be filled.

Elderly and retired, Sensei lives on the outskirts of society, no longer able to fulfill standards of productivity demanded by heteronormative capitalism. Tsukiko’s love for him appears in moments when boundaries between small everyday objects and humans come undone. During a short estrangement between the two, she reflects on how his presence lends an indefinable rightness to the mundane activities of her life. She compares him to an obi, the band wrapped around Japanese book jackets. Later, during a nap, she dreams that she has carefully wrapped him in a piece of cloth to tuck him away in the closet.

In another scene, she visits his house, and he fondly shows her old batteries that he feels too heartless to throw away, using a tester to reveal signs of remaining life. In the text, Sensei himself takes on the qualities of a battery, dearly loved and still giving off gentle warmth; we see that what Tsukiko desires most from him is simply proximity, to be close to him as she feels the warmth emanate from his body. The heat of Sensei’s body radiates faintly yet intensely between them, as intimacy that neither necessitates physical touch nor asks for language or definitions.

Intimacy characterized by the absence of physical touch appears for the last time at the end of the novel, after Sensei passes away and leaves Tsukiko his briefcase. At night, Tsukiko opens it to gaze at the endless expanse of emptiness inside. At different points throughout the novel, Tsukiko calls out repeatedly to him—to the universe, to herself, often a seemingly empty reaching out. At a time when he cannot respond, when it is impossible, what does this repetition produce? She is reaching across some measure of space, towards something somewhere, sending out some form of energy without knowing where it will go. In the final lines of the novel, her call reaches Sensei, whom she hears responding from the ceiling of her apartment: “When I call out ‘Sensei,’ sometimes I can hear a voice calling, ‘Tsukiko’ from somewhere near the ceiling. Feeling the effects of Sensei’s tastes, I’ve started putting cod and chrysanthemum greens into my boiled tofu. Sensei, let’s meet again someday.”[6] Their connection and intimacy live on, embedded in the small space of her home and the food she prepares. This final image is undeniably lonely but also warm at the same time.

These moments and intimacies in The Briefcase are trivial: they lend themselves easily to purely sentimental readings, and they have no obvious political power, arguably both saying and doing too little. But my readings emphasize forms of hope and sustenance produced through seemingly insignificant relations. Assumptions about what is “important,” or what “counts,” overshadow intimacies that might count for much more. Queer readings such as mine offer one way to rethink how we exist in relation to others—by finding alternate possibilities in minor, minimal forms of attachment within the rigid constraints under which we live. My readings describe queerness in the moments we are most likely to overlook, the places we take most for granted.

The last scene of The Briefcase takes on particular meaning in this moment that we are living through—when we call out to the universe, who is going to respond? Our daily rhythms sundered by the pandemic, by political change in Hong Kong and elsewhere, the delightful moments of encounter and pleasure within Kawakami’s everyday feel distinctly different. Alongside the urgency of our everyday worlds falling apart, what can minor intimacies of Japanese literature possibly mean? It is not irrelevant to reflect on the siloed nature of Japanese studies in Anglophone contexts or its lack of clear relevance to Hong Kong. With its Cold War origins and ongoing struggle to grapple with questions of race and imperialism, Asian studies might feel like a less than likely site for radical solutions. But what follows is not a defense of Japanese or Asian studies, nor is it particularly a description of what “Japanese literature” is: instead, it is my account of the unintentional effects of reading Japanese literature and queer theory, a sideways becoming through moments inflected by race, gender, sexuality, and other difference between Japan, the United States, and Hong Kong.

II. Failure: a queer woman of color at the end of the world

Intimacy within Kawakami Hiromi’s The Briefcase takes shape through small configurations of love and pleasure, precariously drawn outside the lines of societal expectations in contemporary Japan. The novel is deeply cognizant of how heteronormativity makes us lonely in the most ordinary, unspectacular, yet cutting ways, and it is also Kawakami at what is possibly her most optimistic: writing tenderly about the wonderful delight and humor of unexpected connection in daily life—which does not dispel the darkness of isolation pervading the everyday but shines through it in moments of grace. Kawakami’s text exudes gentleness; at least, this is how I read it in the past, and have continued to read it in some of the most darkest moments of my life.

Alexander Chee begins his essay “On Becoming an American Writer” by asking, “How many times have I thought the world would end?”[7] He describes his dazed state of mind the morning after the 2016 U.S. election—a vision of a white supremacist government that would deport Muslims, incite violence towards queers and people of color, accelerate climate change, and so on. A few months after arriving in Hong Kong, I taught Chee’s essay to my students to remind them—to remind myself—that it was not the end of the world.

At the time of the 2016 U.S. election, I myself was teaching at a temporary position at a small liberal arts college in the U.S. Along with the collective dismay experienced by Chee and others, I lived with constant dread that my own small world—built around a life in the academy—was about to crumble. During job interviews over the next several years, traveling to over a dozen cities in two countries, sometimes I was treated with kindness and respect, but at other times, with open disdain. Once, I texted a friend to ask, “Is this legal?” I needed to hear that my discomfort mattered, since all I could do in front of most of the world was pretend that it did not matter at all.

It might be astonishing, then, that it was in these spaces that I also found the greatest joy. As time went on, I was stripped not of fear but of uncertainty about who I would be in these moments. Each time, in front of audiences of faculty and students at unfamiliar institutions, feeling my words cut through the silence in front of me, I loved my readings of stories by Kawakami and others; in a remarkably uncomplicated way, I loved who I was.

Many accounts exist of obstacles faced by women, people of color, and other minorities in the academy. Faced with racist, sexist structures that authorize one’s humiliation, one realizes that “failure” is defined and produced through inherently unjust terms. If one is already likely to fail—to secure a job, to secure the right to stay—why do anything but perform your work with complete dignity and pride? In a space that could have been defined by banal despair, there was nothing better than speaking about literature, sharing queer readings of love, hope, and imagination. This was the space of my readings of Japanese literature. It was no one else’s; it was entirely mine.

It was not uncommon for an audience member to ask, “What is the basis of your research?,” despite the many theorists whom I quoted. Most people did not know queer theory; stray questions about lesbianism made it clear that I myself was expected to perform a specific type of “queer.” My queer readings were sometimes obviously suspect, not the type of “queer” expected or desired. Not queer enough, not feminist enough, not radical enough—not enough. But as a queer woman of color, I never once regretted choosing to do work centering my own psychic survival.

Later, in Japan and Hong Kong, in classrooms and other spaces, I began to reflect on what might be offered by the imagination of queer readings, an impulse tied closely to my own forms of failure as a queer woman and a racial minority. Transplanted from small liberal arts colleges in the U.S. to East Asia, I observed how feminism was stigmatized, queers often preferred to stay in the closet, and young people struggled to mold themselves to unforgiving neoliberal capitalist standards. At the very least, I wanted to share my queer feminism, and I wanted literature to mean something.

Trying to stay afloat in Hong Kong, I was desperate to make literature, or words, mean something. Years ago, I had worked briefly with trauma theory as a Ph.D. student. But I had never imagined moving to Hong Kong, then coming to know it—during a pandemic, after protests followed by the passing of the National Security Law in 2020—as a space of collective trauma and loss. It had never occurred to me that I would find myself repeatedly asking what it means to create queer intimacies in darkness of this magnitude, in which the world does not really end, but we continue to go through the motions of daily life with muted sadness and anger palpable in the air.

In these moments, I found myself returning to my queer readings of a novel about failure—Ekuni Kaori’s popular 1991 novel Twinkle Twinkle, which describes a marriage of convenience between a depressed, alcoholic straight woman and a gay man. Advised by a male psychiatrist that marriage will improve her mental health, Shōko enters into a sham marriage with a man named Mutsuki as they both attempt to perform conformity to satisfy their parents. The novel follows Shōko’s persistent grief over her failure: not only the failure to conform to gendered expectations for women, but to be loved by Mutsuki. Her tears overflow through the text, shaping it with chapter titles such as “The Cage of Water” or “Where the Water Flows.” Along with her tears, imagery of stars suggests the helpless nature of the characters’ longing for seemingly unattainable forms of intimacy. Other chapter titles describe constellations, the moon, and stars.

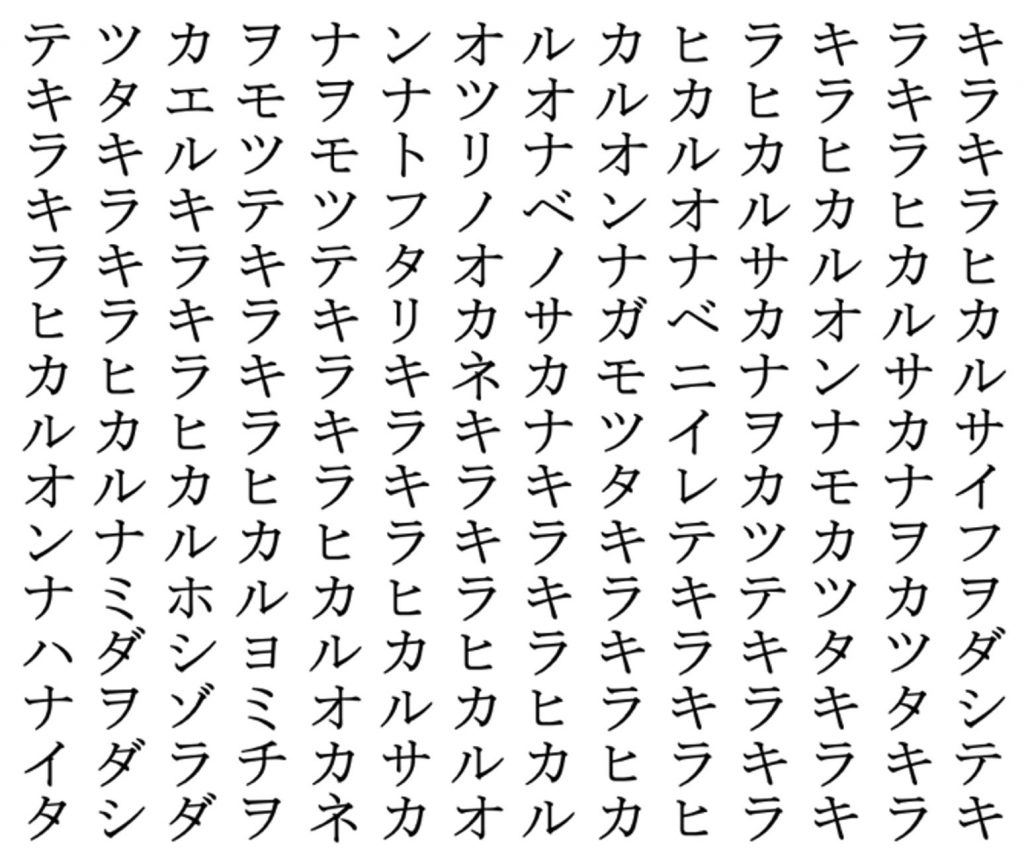

Ekuni borrows the title of her novel from the 1955 Japanese poem “Kira kira hikaru” by Irisawa Yasuo (Image 2), held together by the constant repetition of kira kira hikaru, translated more literally as “twinkle twinkle sparkling.” While the poem is meant to be read vertically from right to left, the words kira kira hikaru repeat in every column, cutting diagonally across the poem from top left to bottom right, and the top and bottom rows can be read horizontally from right to left. The poem describes the ordinary day of an unspecified subject—a fish being bought, a woman being bought, heading home with the woman, and finally, the tears of the woman. It ends with the lines, “it was a twinkle twinkle sparkling starry sky / letting out twinkle twinkle sparkling tears / the twinkle twinkle sparkling woman wept.”

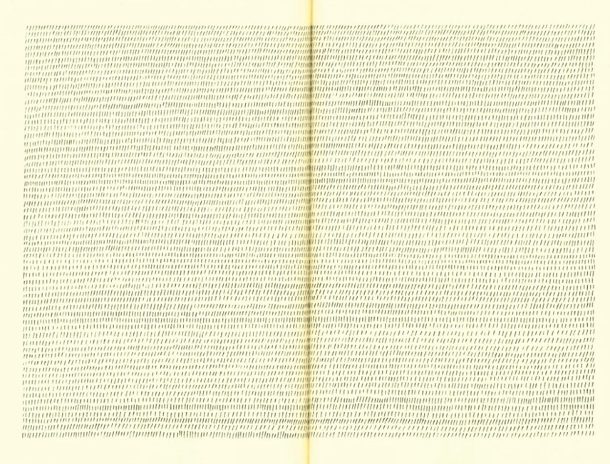

What do we make of the tears of a woman? Written entirely in katakana, a script usually reserved for loanwords in Japanese, the poem takes on a graphic, patterned appearance with its sharp edges. It hints at the sight of countless prickles of searing light, stars sweeping across the night sky, a dazzling flood of tears. The stunning visuality of this poem simultaneously centers the woman’s sorrow and renders it insignificant, turning it into the opportunity for a clever writerly feat playfully referencing a children’s song. The woman’s tears become purely decorative; her sadness is trivialized. She herself becomes an inscrutable figure lost within the repetitive, mechanical strokes of the poem.

The twinkling of tears and stars also signifies a highly gendered aesthetic—decorative, dreamy, flickering, insignificant. Nonetheless, in Ekuni’s novel, the crying woman Shōko functions not only as a figure of self-destructiveness and weakness, but also as one of minimal hope. Entering this marriage with no expectations of love, she nonetheless finds love and fights to protect it. Not only does she defy parental disapproval, but she also wholeheartedly welcomes her husband’s lover, secretly helping him purchase an apartment in the same building as their own home. Early on, she thinks despondently about the odd unreality of their life together. But later, she recklessly throws herself into defending this space when it becomes unexpectedly dear to her; she rejects the lack of imagination deeming her love too inauthentic or worthless.

Outlining the close relationship between failure and lived experiences of queerness, Jack Halberstam produces a counterintuitive reading of failure, arguing, “Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world.”[8] In several scenes, Shōko drunkenly waters the plant from her husband’s lover with whiskey and tea; she clumsily “waters” the text with her excessive tears and liquor, creating possibilities for unlikely new forms of love. As Ekuni’s imagining of the crying woman in Irisawa’s poem, she is unbearably beautiful in the painful brilliance of her tears.

Twinkle Twinkle offers no definitive happy ending but suggests that tears and stars embody the tentative possibility of love, not only grief. As I describe elsewhere, Twinkle Twinkle and other writing by Ekuni serve as a lesson for how “openness and honesty, vulnerability and awkwardness, as well as the willingness to commit in potentially painful ways, might also allow us to create queer intimacies within the night.”[9]

In the U.S., I was a responsible and occasionally inspiring instructor, and in Japan, I spoke and wrote publicly on gender and race in the academy. In Hong Kong, I began to teach and speak with an entirely different combination of patience and audacity. Weekly homework assignments turned into my excuse to ask students how they were doing or try to offer them comfort. Grading papers, I wrote not only about grammar and citation issues but also about hope and agency in response to students’ experiences of sexism, homophobia, and racism or their grief over Hong Kong. I wished to demonstrate a model of queer feminism acting as a critique of the inhospitable world in which we live.

My first year in Hong Kong was particularly described by desperate hope, and love. How does one manage to believe in life-giving connection through the transient space of an online classroom, separated by a level of distance and silence that often seems insurmountable? An instructor experiences a sense of failure when weeks go by with almost no students turning their cameras on. It is a certain kind of hell to wait every week wondering if you will be lucky enough to hear your students’ voices. I grasped a few of the biggest pieces in terms of why failure was perhaps inevitable. The relentless coloniality of English in Hong Kong means that students frequently lack confidence speaking English. The Hong Kong education system does not encourage the type of self-reflexive discussion that I value; it does not foster spaces for conversation about topics such as misogyny or colonialism. And of course, this is an era of surveillance.

Kadji Amin cautions queer studies scholars about the need to recognize the origins of Anglo-American queer theory in the U.S. 1990’s and to “ground queer in its various contexts, histories, genealogies, and inheritances.”[10] This means that we must let queer “come not only to mean but also to feel differently than it does now.”[11] In Hong Kong, queer definitely means and feels differently. First, this is true in terms of a literal sort of translation, how one must grasp basic ways in which queer theory and U.S.-centric LGBTQ politics perform differently refracted through the linguistic, racial, and cultural hierarchies of Hong Kong as a (post)colonial space.

Within my classrooms, queer has also meant broader faith in acts of translation: I teach on heteronormativity, feminism, and LGBTQ communities in Hong Kong, mainland China, and Taiwan, but I also assign readings on Anglo-American queer theory and woman of color, postcolonial, and transnational feminisms dealing with the U.S., Japan, Korea, and India. It has meant believing that, as a Taiwanese American who still knows little about Hong Kong, I myself—and what I know about queerness and feminism—can still translate for Hong Kong. And what I want most to translate is described perfectly by bell hooks when she says, “[T]heory could be a healing place” (emphasis mine)—it might be “healing, liberatory, or revolutionary” if we orient ourselves towards this.[12]

It is often unclear what translates. Soon after arriving, faced with glimpses of injury and despair around me, I was swallowed up by my own sadness coming into contact with everything that separates people in Hong Kong: painfully ordinary divides of language, colonialism, racism, xenophobia. Yet this was also why I felt queer in a different sense, removed from the responsible, meticulous teaching of theories and texts. As I began to find my place in Hong Kong, queer turned into new patience with everyday failures to make things work, an acknowledgment that there were too many reasons for students to remain silent. At the same time, queer was a willingness to let go of what I was ostensibly teaching—to make room for anger, frustration, hurt, and questions that students wanted to articulate. Sometimes I asked students to do more, I pushed them to step up, but mostly, I tried to wait and trust. Queer was all the small ways that I found on an everyday basis to tell students that what they saw as their own weakness or failure—or the greater loss that they saw as defining the future of Hong Kong—was not the end.

With my pedagogy in Hong Kong, perhaps I have wanted to create a safe space of healing, comfort, and pleasure—the world that I first found through queer theory and Japanese literature—and this has been impossible. I think dryly sometimes about the ludicrous nature of my enthusiasm: a small garden that I am tending with the greatest care within a horrific storm. I can protect nothing; I can only be there next to them for a few brief moments: providing partial shelter, trying to wait it out together.

My first year in Hong Kong, I taught Japanese literature only once: in the form of excerpts from Stephen Snyder’s translation of Ogawa Yōko’s The Memory Police, a novel about the disappearance of things, people, and memories on an unnamed island. In the novel, a character comments on how, over the years, the disappearances have made the hearts of the islanders “thinner” and “full of holes.” In class, I told my students that what I had attempted over the past few months was to give them more words, more stories, in the hope that their hearts would never grow thin. I said: I cannot promise that words—and things—will not be taken away from you, but I can use queer and feminist writing to show you the freedom of imagination, varied and remarkable forms of love that have been lifelines for others, that might be the same for you, that might inspire you to “love life and love people around [you] in the deepest ways possible.”

Feminist feelings often involve outrage—the familiar figure of the “killjoy,” the woman who is negative, loud, and always angry. It should be better known that feminism does not only tear down but also nourishes and embraces in ways that might truly extend into lifelines. This queer feminism builds on the tenderness and strength of Margo Okazawa-Rey, Sara Ahmed, and other women of color feminists. In the form of reading practices, it draws most obviously from queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s concept of reparative reading. Sedgwick writes, “Because there can be terrible surprises…there can also be good ones,” suggesting that exposing injustice need not rule out practices of pleasure and hope.[13]

Feminist and queer anger is sorely needed in a world of misogyny and hatred for queers, in which racism, xenophobia, and colonialism take on appalling new meaning in divides between Global North and South seen in contexts of the pandemic. But because the world is imperfect, we also need queer feminism that is unabashedly about how we care for others. Within contexts of failure that might break us, we need texts and readings about hope, pleasure, surprise, creativity, generosity, wonder, and love.

III. The minor, or a nighttime parade

A literary studies scholar is often white and/or male. “He” is a good fit. A literary studies scholar must do work that is clearly difficult. We are sometimes allowed to work on authors that move us; we are generally not expected to move others. We can write about feelings and bodies in novels but only while pretending that our feelings and bodies do not matter. We must not be accessible. If we attempt relevance, we may borrow from a finite list of academic buzzwords. Our writing is not poetry; it is not fire.

Chee tells us, at the end of the world, to write for our dead and also write for the living: “The ones you love, and the ones who are coming for your life. What will you give them when they get there?”[14] How does a queer feminist scholar of literature respond to this question at the end of the world? How do I respond here?

The word “minor” in my project goes along with words about the everyday: repetition, routine, lack of progress, and boredom, what is trivial, fleeting, and escapes our notice. Situating women writers within the shifting gender politics of contemporary Japan, my research relates tangentially to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s theorization of minor literatures as “that which a minority constructs within a major language.”[15] With my emphasis on uncertain, ambivalent intimacies, I draw upon Sianne Ngai’s study of minor feelings, or “ugly feelings,” such as anxiety and irritation, which are “less intentional or object-directed, and thus more likely to produce political and aesthetic ambiguities.”[16] My “minor” aligns with Lauren Berlant’s theorization of minor intimacies as “desires for intimacy that bypass the couple or the life narrative it generates,” or “glances, gestures, encounters, collaborations, or fantasies that have no canon.”[17]

But what are all the ways in which “minor” might come to mean and to feel differently for an Asian American queer female scholar and writer such as myself in this moment? Asian American writer Cathy Park Hong describes the everyday gaslighting of Asian Americans in the following way: “Minor feelings occur when American optimism is enforced upon you, which contradicts your own racialized reality, thereby creating a static of cognitive dissonance.” [18] And yet my own racialized experience is not the one explained by Hong but instead unfolds as multiple realities across borders—my shifting embodiment of privilege and marginalization bound up in a sense of accountability to more than one place.

After long pent-up grievances, many Asian Americans embrace Hong’s words as if no one else has ever described the Asian American experience before. Meanwhile, recent conversations in the U.S. find a place for Asian Americans in Black and Asian solidarity, drawing attention to a history of activism marked by the 1968 Third World Liberation Front and prominent figures such as Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama. But even while referring to the transnational, they can reproduce U.S.-centric models of race and hierarchies of oppression. And there is, unfortunately, no perfect blueprint for whom or what to center in each moment of the day when caught up in transnational currents of feeling that refuse to fall neatly into place, if one is Asian American but situated—if only in the most basic sense—outside of America.

There are no simple instructions for how one’s feelings and attention should be devoted when you are connected not only to the U.S., but also to Japan and its overlapping histories of racism and imperialism, when earthquakes result in hate speech against Koreans or when a Harvard law professor—supported by rightwing Japanese extremists—claims that the accounts of “comfort women” are complete fiction. As anti-Asian violence makes fear part of the everyday for Asian Americans, in Hong Kong, domestic workers—largely from the Philippines and Indonesia—are regularly abused and repeatedly targeted by harsh COVID regulations. “Minor”—if it is mainly about the marginalization of Asian Americans—says little about the plight of mainland Chinese students, faced with xenophobia in countries around the world. It says only a bit about the strange, highly particular nuances of my own experience as a Taiwanese American in Japanese studies, an Asian American woman in the white- and male-dominated field of Asian studies, a Taiwanese American in Hong Kong, and so on.

The transnational demands nuanced narratives for how we are accountable. It does not offer false accounts of equivalence in terms of oppression, but it also rejects predetermined answers. It asks for kinder understandings of how we might show our solidarity. We need to remember that some work takes more time, that it might perform without being (publicly) performed. Our feelings take time to work through, through a multiplicity of realities and narratives. As a woman of color in the world, I keep imagining alternate paths to move through the injury and complaint of some minor feelings to those ultimately taking shape as solidarity—even while accepting that this might be imperfect, tentative, or in passing.

To find these paths, I return to what is described by Shu-mei Shih and Françoise Lionnet as “minor-to-minor networks,” focusing not on what happens between center and periphery, but on what happens—or what might be possible—between the marginalized, those on the periphery.[19] Writing on the potential of minor transnationalism for Hong Kong and queer Sinophone studies, Alvin Wong calls it “creative comparison that entangles Hong Kong with the world through alternative methods of reading and queer genealogies.”[20] As a scholar of Japanese literature in Hong Kong, working adjacent to the Sinophone, I continue to fumble in the dark for ways to entangle Hong Kong with the world in terms of queer and feminist lifelines. What are all the words and things possibly lending themselves to this, and what does it signify when I perform and embody this entanglement?

In March, a week after the Atlanta shootings, I spoke through tears about the deaths of Asian women in the U.S. to students in my gender studies class: to Chinese students “like” me yet not, to South Asian students whose “minor” experience in Hong Kong is “like” and yet “unlike” that of an East Asian woman from the U.S., to others both “like” and “unlike.” In the classroom, I take off my armor; I exist as a version of myself that exists nowhere else. This is a space that exists for students but also functions as one in which I am made both legible and legitimate. But outside, my anger and grief—and all the better feelings—turn into fodder for a process of tokenization in white, liberal, and/or colonial spaces that take no responsibility for their violence. Each time, as I perform in character, I think about what will exceed the limits of this consumption; I take a bet on excess produced through my voice, reaching others for whom the “minor” means something.

The “minor” that I feel right now—my desire to perform a type of queer, feminist, anti-racist, anti-imperialist entanglement with the world, regardless of whether it is trivial, small, or goes unrecognized—builds on Berlant, Ngai, and others but cannot be removed from the specificities of my own racialized experience. It can be traced back to how I already began borrowing long ago from scholarship on Asian American literature with my readings, forming an unlikely bridge between Japanese literature and my lived experience as Asian American that I am only now able to better articulate from Hong Kong.

In a study of the everyday in Asian American literature, Yoon Sun Lee traces “minorness” and “minimal sociality” through the industrialization of the early twentieth century, the uncanny nature of life for Japanese Americans in internment camps, postwar memoirs, and contemporary writing. The experience of racial minorities is reflected in people, objects, and acts defined by smallness and sometimes blankness in the everyday. But Lee also finds something more in “both the limits and the possibilities of mere proximity, of things and persons that exist side by side without knowing or affecting each other.”[21] She sees utopian possibility in how one might begin with what is small, static, and abstract but discover that “adjacency represents a possible path of movement.”[22]

Rereading Lee’s writing years later during a pandemic, I ask: What does it mean to exist side by side, and with what limits and possibilities? How do we acknowledge the violence, grief, and beauty of this connection, or non-connection? For some of us, the painful fragility of our communities is newly exposed, stretched thinly over multiple parts of the world—no longer just “here” and “over there,” but too many iterations of “over there,” multiplied endlessly when it comes to the people and places we love.

In my earlier reading of Kawakami Hiromi’s The Briefcase, intimacy between the characters arises from—building on Lee’s work—what I call their side-by-sideness, as well as a lazy sort of time that refrains from any sense of progress, taking shape as indistinguishable days flowing by one after another. There is nothing goal-oriented about this intimacy; it requires no purpose. Sensei and Tsukiko, and we as readers, do not need to see that their story “goes” somewhere. But outside of novels, out in the world—amidst countless farewells in Hong Kong today—it is a different sort of struggle to make peace with the anguish of new forms of separation and distance, the understanding that “we” (together) might not be able to go anywhere at all.

In Kawakami’s 2002 novella Parade, a side story to The Briefcase, the limited nature of hope in the everyday is starkly visualized through Yoshitomi Takako’s illustrations. With a story of small creatures and small events, Parade draws out more fully the minimal forms of connection suggested by The Briefcase. The novella depicts Kawakami’s imagining of an ordinary day that Tsukiko and Sensei might have spent together. The two prepare lunch together and then, stomachs full, sprawl down on the floor in Sensei’s house. Prompted by Sensei, Tsukiko tells the following story about her childhood.

One morning, in elementary school, she wakes up to find two strange creatures following her around and chattering in an indecipherable language. She realizes that they are tengu, Japanese long-nosed goblins. Both very small, they are clearly children, too. Her mother recognizes them, allowing them to lick the margarine at breakfast. At school, she finds that certain other children also have creatures next to them—a badger, a rokurokubi, a small old lady. They can see her tengu as well.

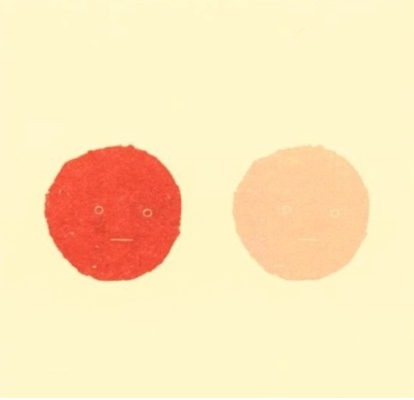

The tengu are companions, also gendered materializations of the child Tsukiko’s conscience. The red, male one does not see any problem with hiding her grades from her mother; the light-red, female one insists that she show them and later becomes unwell when another girl in the class is bullied. One day after cram school, she encounters this girl despite all her efforts to avoid her. Overcome with shame, after an awkward exchange, she suddenly tells her about the tengu, and the girl Yūko gently speaks to them. Eventually, the ostracization stops without the two girls ever becoming close. But Tsukiko recalls that, after their chance encounter, something would happen everyday: “Once a day, without fail, the two tengu would go up to Yūko and touch her. When that happened, Yūko’s body would sparkle with light—like a nighttime parade. It was an extraordinarily sad, yet beautiful light.”[23]

As extensions or proxies of the child Tsukiko’s minimal kindness, the tengu children reach out to the other girl, the affect materializing as light—as gentle warmth, marked by sadness. This is an unreal sort of light, which exists in the space of the everyday and yet does not: a nighttime parade, coming to life when we share our dearest secrets and forms of imagination, as a faint protest against our weakness. No one is transformed, nor is anyone saved. But this turns into an inexplicable habit of caring that produces something, which is certainly more than nothing.

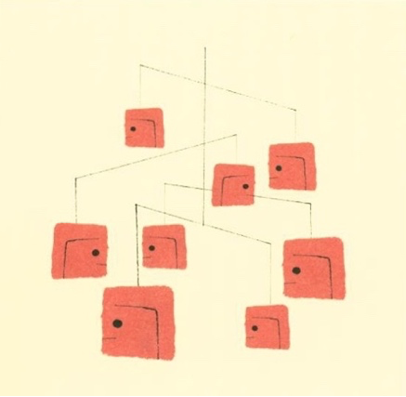

Image 3: Illustrations by Yoshitomi Takako in Kawakami Hiromi’s 2002 novella Parade

The meaning of the title Parade is expressed artfully by Yoshitomi’s illustrations. The appearance of the tengu is marked by an illustration of two circles (Image 2a), with interaction between the children shown through images of red blocks (Image 2b). Several times, a two-page spread covered with rows of tiny black dashes (Image 2c) appears, echoing the sharp grief of a woman’s tears found in Irisawa Yasuo’s poem. In this way, the children and their lives are abstracted. They are small, unremarkable, and nearly indistinguishable, faceless and emotionless. Whatever happens in the world of a child is too small for notice. In their daily lives, they are simply there, next to each other, without going anywhere. Smallness, side-by-sideness, and separation form this world—in such a world, where can a parade possibly go? What can possibly be on display in such a parade?

This spring, a friend spoke to me about returning to their country after a long absence to what they expected to be isolation, only to have the experience of traveling between cities, warm and joyful moments of meeting other feminists who had only been names and flat images on computer and phone screens. To them, these friends appeared as sparks of light dotting what had appeared to be a vast, empty expanse of space defined by darkness. Soon after, they and another former student began translating a lecture of mine on “building a queer feminist life” to share with others in Chinese. When my former students share these stories, or perform the love and labor of translating my work to share among pinpoints of brightness in the dark, they show me a bigger picture of spaces that I myself have never seen—or even known to take note of—which now light up softly in my mind with the faith that we are indeed connected.

Minor intimacies of Japanese literature—and minor readings of them—are no more than this. They are about a slow-burning sense of hope, a minimal yet enduring belief that when you call out, someone will hear you, and something will spark in our encounter. During the day, our insignificant acts of warmth and courage might be swept into blankness, made illegible in the chaotic noise of ordinary life, by too much grief swirling up from different corners of the world, and by larger forces that attempt to suppress the truths of both injustice and love.

During the day, the blankness of abstracted children is how a parade might appear; only at night does the parade come alive with light, and tenderness. The night is full of tears; it, too, might seem to stretch on forever. But it is also only at night that the brilliance of a parade becomes absolutely clear, where we come to know each other differently, where minor intimacies come to life in the darkest of moments.

Grace En-Yi Ting 丁恩宜 グレイス・ティン (Ph.D. Yale University) is an Assistant Professor of Gender Studies at the University of Hong Kong. She specializes in queer and feminist approaches to Japanese literature and popular culture, with a focus on women writers and girls’ culture. She also writes on problems of race and gender in the academy. Her current research situates Japanese literature within transnational encounters with queer feminisms and the Sinophone, theorizing the unexpected significance of queer reading practices across boundaries for marginalized readers in precarious times.

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.