This piece explores how public health campaigns in Singapore surrounding diabetes stigmatize and shame individuals and ethnic communities. It also highlights the potential for reclaiming this shame to challenge ineffective, individualizing public health approaches and their underlying narratives.

This piece is the first of three that aims to explore the connections between diabetes and shame on multiple levels in Singapore. In this particular piece, we sketch the landscape of diabetes in the island nation, presenting the overarching public health narrative of the ‘War on Diabetes’ campaign, a feature of the 2017 National Day Speech. We also elucidate how public health campaigns shape emotional structures that often engender shame among individuals with diabetes. Singapore’s unique political and racial history means that diabetes and shame are not immune from being racialized. Essentially, the public health narrative shames individuals and ethnic communities by highlighting certain behavioral and cultural ‘deficiencies’ that have allegedly led to high diabetes prevalence in these specific groups. This piece also underscores the transformative potential of reclaiming shame by those who have been shamed, challenging the ineffectiveness of neoliberal and individualizing public health approaches.

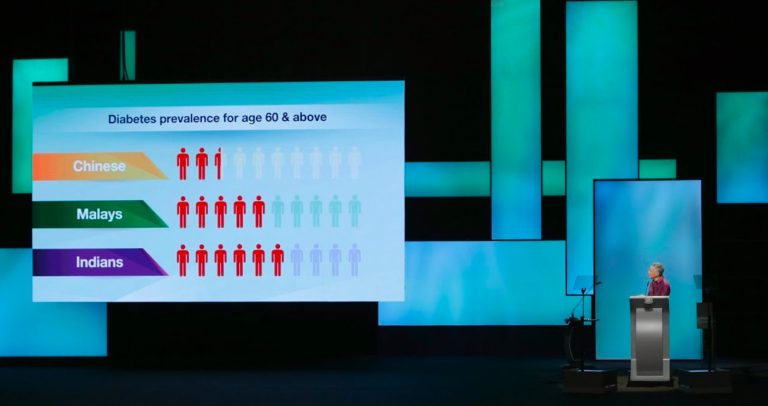

Figure 1. YouTube thumbnail from the 2017 Singapore National Day Rally, showing Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong displaying diabetes prevalence rates among ethnic groups. CNA. “3 in 10 Singaporeans over 60 Have Diabetes (NDR 2017).” YouTube video, 0:35. August 20, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jx8qJWa1H2o&t=35s.

In 2016, Singapore’ Ministry of Health declared a War on Diabetes. Anticipating an increase in the cases of type 2 diabetes cases that would cost the nation a whopping S$2.5 billion by 2050, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong reiterated the urgency of the matter in a 2017 national day address, calling for Singaporeans to take charge of their health (and future) by eating healthy and exercising regularly. [1] This ensures that Singaporeans will live a healthy life, free of complications brought about by diseases such as diabetes, when they get older. The Prime Minister also highlighted the severity of the problem among the Malay and Indian ethnic communities, calling it a health crisis. This is captured in the thumbnail above. In a separate Malay language address, the Prime Minister went as far as highlighting the health harming nature of Malay cuisine.

In her discussion of emotions in social life, sociologist Arlie Hochschild highlights the importance of feeling rules, which are social guidelines that shape how we think we should feel in certain situations.[2] Say we just ate half a pint of ice cream after dinner on a Thursday night. The inner dialogue over whether one should have eaten ice cream will likely involve feelings of shame and guilt. We then ask ourselves why we keep succumbing to vigorous snacking, which has, among other things, led to our pants getting tighter around the waist. But then we might also rationalize this behavior by invoking our tough week and saying we deserve to indulge in some ice cream. Self-care is not selfish! In this example, we see a negotiation shaped by feeling rules. On the one hand, we see how social guidelines on healthy eating and lifestyle shape how we should feel about consuming (too much) ice cream. Then, we also have emergent narratives of care and body positivity, for instance, which present new guidelines for how we should feel.

Figure 2. Ondeh-ondeh, a dessert made with palm sugar, glutinous rice flour, and coconut. In his 2017 National Day Malay speech, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong expressed his fondness for ondeh-ondeh but noted his doctor’s disapproval of eating more than one piece due to its decadence. ProjectManhattan. “Ondeh ondeh kuih.” Wikimedia Commons, May 7, 2014. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ondeh_ondeh_kueh.jpg.

The objective of encouraging behaviors that minimize the risk of ill health is perfectly logical and rational. However, the issue is that health problems such as type 2 diabetes have also been shown to stem from social determinants of health. Precarious employment, access to recreational time and space, food environment, built environment, and poverty have all been correlated with the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes among populations.[3] Yet, these factors were barely mentioned, if at all. Instead, individuals and ethnic groups were framed as public health targets to be nudged into modifying their behaviors and habits to stave off diabetes and minimize the disease burden nationally. This public health framing of diabetes raises the question: How does it shape the way people with diabetes feel about their communities and themselves?

Figure 3. Side view of klepon: rice cake balls filled with palm sugar and coated in grated coconut, resting on a banana leaf and woven basket. Joseagush. “Klepon Side View.” Wikimedia Commons, January 5, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Klepon_Side_View.jpg.

Despite attaining national independence decades ago, Singapore, a former British colony, stubbornly maintains aspects of coloniality; remnants of colonial orientations, attitudes, and structures remain pervasive. Singapore is quite possibly the only nation to celebrate its colonial history by erecting statues of colonial figures such as Stamford Raffles. Crucially, the Singapore state continues to utilize colonial racial categories in the governance of its citizen body. The valorization of colonial figures and knowledge structures has only passed with criticism. Various actors and institutions have pushed for dissolving colonial racial categories (CMIO). There have also been theater performances, writings, and discussions that question the continued adulation of Raffles. As a nation then, Singapore is still grappling with decolonial projects (dealing with coloniality in the political economy, vested interests in the material world, and the link between ideas and the material world) and postcolonial (dealing with discourse).

The late Syed Hussein Alatas, an intellectual giant in Southeast Asia who problematized and conceptualized solutions for social issues such as corruption, the lack of functioning intellectuals, and the need for a decolonial approach, also wrote about the social psychological function of shame. Alatas asserts that shame can motivate individuals, particularly individuals who wield influence in society, to correct injustices in the world.[4] However, shame can also damage the individual and broader society in very insidious ways. Among the formerly colonized, for instance, some still exhibit traits of what Alatas terms the ‘captive’ mind. The person with a captive mind feels shame and deals with this shame by mimicking what they believe to be the former colonizer’s ‘superior’ culture and civilization.[5] They will feel that they got rid of the shame of being part of an “inferior” colonized culture and civilization by “transcending” through the adoption of the colonizers’ identity, social norms, and ideology. This way of dealing with shame, according to Alatas, is dysfunctional and doesn’t necessarily address broader social structural issues, leadership, and the agency of people.[6, 7] For this research, we adopt Alatas’ lens of understanding shame to interrogate the ascription of negative qualities, values, and consequences of minorities’ lifestyles, food, and attitudes as elements that are to be blamed on the victims; individuals, their cultures, and their communities.

Shame can also be a gateway to empowerment that shapes revolutionary reformations of the localities, experiences, and dynamics in which persons with diabetes are embedded. French scholar Frédéric Gros explains that shame can be turned from the self and towards oppressive, unjust, and debilitating structures (désobéissance politique), systems, and situations, where it is made of sadness and fury (la honte est un composé de tristesse et de rage). [8] Where shame is directed at certain individuals or groups for not leading a healthy lifestyle, for instance, it can be reoriented to interrogate social and historical structures that produce said shame. When thinking about shame in Singapore’s War on Diabetes, how does decolonization figure in the subversion of shame? How do such instances manifest? What are the conditions for this revolution to reclaim the sovereignty of the body, wholesomeness, and spirit of persons with diabetes?

Shame then encapsulates an affective phenomenon affecting the individual and group with diabetes, as well as recalibrating that emotion and feeling to carve out the banks through which their self-empowerment can flow and lead them into oceans of liberation, as outlined by Gros. At the same time, Alatas’ notion of shame is essential when individuals or people are treated unjustly. Feeling shame is vital as part of what he calls ideals of excellence; these ideals aspire towards a just, decent, and dignified society. But this situation might only occur if individuals, groups and leaders, professionals, and those playing various roles from various domains, including cultural, religious, literary, social service, civil society, and so on, decolonize and look at the systemic, structural, and symbolic currents that animate shame. Then, can they truly feel shame against injustice in the systems, structures, and metaphors/myths that serve to disempower persons with diabetes?

Figure 4. Klepon: a close-up view of chewy rice cake balls filled with palm sugar and coated in grated coconut. Ayunda, Deswinna. “Chewy Sweet Dessert.” Wikimedia Commons, January 22, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chewy_Sweet_Dessert.jpg.

This research series, grounded in the lived realities of persons with diabetes, sets the slight intention and attention on setting shame-free and transforming it into the source of inspiration to better reforms in the healthcare system, perspectives, and values while holding on to the value of shame, in a contextualized manner.

Faris Ridzuan has played roles in various fields like policy, strategy, research, manpower planning, teaching, facilitation, coaching, mentoring and the arts. He has led teams or projects in organisations such as the Singapore Public Service, a leading tech company, a global climate change and mental health advisory, and the Global Indigenous Youth Summit on Climate Change hosted by the United Nations Institute of Training and Research and Future Earth. He has worked as a 3P consultant and trainer in curriculum development, educational strategy, diversity, and security related issues. Faris publishes in Malay and English primarily, on platforms like Taylor and Francis, Springer Nature, BERITA, Fulcrum, ISEAS Perspectives, Karyawan and Journal UIN Said. His publications also appear in BERITAMediacorp, the Straits Times, Berita Harian, and literary and art magazines like The MockingOwl Roost. Faris has won five international awards and one local award for his music. His musical accomplishments are featured in local, university and international publications and media. He recently released his original song “Holding the Love”. Faris received two university teaching awards and a social service agency’s Super Teacher Award. He also received the National University of Singapore Outstanding Young Alumni 2023 Award. His music and publications are on https:/

Mohammad Khamsya Bin Khidzer is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Institute for History at Leiden University. His research focuses on race, diabetes, and public health in late colonial and postcolonial Singapore, examining how diabetes emerged as medically, culturally, and politically salient in society. Mohammad is broadly interested in the social studies of science and medicine, medical sociology, Southeast Asian Studies, and ethnic and racial identity formation. He has published research on race, diabetes, and public health in Singapore, and co-authored work comparing how ethnic communities in Vietnam and Singapore interpret data from population genetics research. As a researcher at Leiden University, Mohammad continues to investigate the afterlives of colonial medicine in Southeast Asia with a particular focus on the science of body shapes and disease risk, while also working on his book manuscript on the construction of Asian Diabetes in postcolonial Singapore. Check out his website here: mohammadbinkhidzer.

[1] Alatas, Syed Imad. “Developing a School of Autonomous Knowledge.” In Syed Hussein Alatas and Critical Social Theory: Decolonizing the Captive Mind, edited by Dustin J. Byrd and Seyed Javad Miri, 15-17. Vol. 233. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

[2] Byrd, Dustin J. “The Psychological Dynamics of Mental Captivity, Subsequent Conceptual Developments.” In Syed Hussein Alatas and Critical Social Theory: Decolonizing the Captive Mind, edited by Dustin J. Byrd and Seyed Javad Miri, 82-84. Vol. 233. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

[3] Den Braver, N. R., J. Lakerveld, F. Rutters, L. J. Schoonmade, J. Brug, and J. W. J. Beulens. “Built Environmental Characteristics and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Medicine 16, no. 1 (2018): 1-26.

[4] Gros, Frédéric. La Honte Est Un Sentiment Révolutionnaire. Paris: Albin Michel, 2021.

[5] Hochschild, Arlie Russell. “Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure.” American Journal of Sociology 85, no. 3 (1979): 551-575.

[6] Ibrahim, Zawawi. “Demythologizing Dominant Discourses, Syed Hussein Alatas’ The Myth of the Lazy Native and the Discourse on Malay Cultural Values and Underdevelopment.” In Syed Hussein Alatas and Critical Social Theory: Decolonizing the Captive Mind, edited by Dustin J. Byrd and Seyed Javad Miri, 221-223. Vol. 233. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

[7] SPH.NUS.EDU.SG. “Cost of Diabetes to Singapore to Soar beyond $2.5b by 2050.” April 14, 2016. https://sph.nus.edu.sg/2016/04/cost-of-diabetes-to-singapore-to-soar-beyond-2-5b-by-2050/.

[8] Williams, Claire R., and Barbara Buttfield. “Beyond Individualised Approaches to Diabetes Type 2.” Sociology Compass 10, no. 6 (2016): 491-505.