Sometimes things die. Sometimes things come back to life. Sometimes things come back into our lives in ways that we do not necessarily recognize.

Sometimes things die. Sometimes things come back to life. Sometimes things come back into our lives in ways that we do not necessarily recognize.

‘Motherboard’ is the term Hong Kong–based artist Ha Bik Chuen (b. 1925, Xinhui, Guangdong, d. 2009, Hong Kong) invented for his collagraph plates. An immigrant of working-class background and no academic art training, Ha came to Hong Kong via Macau in 1958 and established himself as part of the Hong Kong art scene in the 1960s. Unlike computer motherboards that conduct electronic and digital signals, Ha’s motherboards are decidedly analogue constructions. They are assembled from wooden and other found materials through highly labor-intensive processes. Their surfaces often feature a combination of textures created by manipulating materials such as wood scraps, sawdust, paper, rattan and jute. The “mother” in ‘motherboard,’ therefore points towards the plates’ potential and process of engendering ‘offspring’, Ha’s collagraphs.

Throughout his life, Ha created over 100 motherboards, which he used to produce over 1500 editioned collagraphs, and likely an equal number of, if not more, test prints. Ha’s collagraph-making practice was at its peak during the 1970s and 1980s, when it sustained him as well as his wife and their five children. Some of Ha’s collagraphs were gifted to artists, curators, and art dealers as Christmas greeting cards. Ha meticulously kept a notebook of his gifting, detailing who received which editioned print. There was even a column for recording reciprocal prints, which for years, remained empty. Ha once wrote that he had hoped to start a culture of sharing and gifting each other hand-made prints and greeting cards, but the lack of response left him disappointed. Some prints were collected by museum and private patrons, others were submitted as entries to international print biennales and some circulated as commodities, bought and sold across Asia, Europe, and North America. The means Ha used to insert his collagraphs into circulation, whether personal, informal, or through formal exhibitions, reflect a level of strategy and a desire to be seen and recognized in a larger art world.

Ha’s handmade motherboards were repurposed from materials he found around the working-class neighborhood of To Kwa Wan, which he lived till the end of his life in 2009. Although most of the motherboards look like they are of a standardized size of 61 by 79 cm, each of them varies in size when measured individually, reflecting their handmade nature. The process of making a motherboard was laborious: once a frame was constructed, multiple layers of plywood were laid on top for thickness. Sometimes, Ha used a blow torch on the found wood in order to evaporate any lingering moisture, leaving burnt marks on the motherboard’s rear. To compose an image, he might carve out negative spaces on the motherboard’s top layer to make room for a wooden inlay; pour a layer of sawdust-and-glue mixture on a motherboard surface to create texture that resembled faux rock; or press ropes and leaves onto the motherboard surface (Figure 1). A huge leaf that Ha foraged in Macau became the main motif that covered almost the entire board surface of Fossil (1981) (Figure 2). A friend later recounted to me that the leaf was from a breadfruit tree; and before being was “fossilized,” had a fuzzy texture. A layer of industrial lacquer, generously poured over the motherboard surface, sealed the entire composition when the image was completed. According to one of Ha’s sons who used to assist him, each motherboard took months to compose.

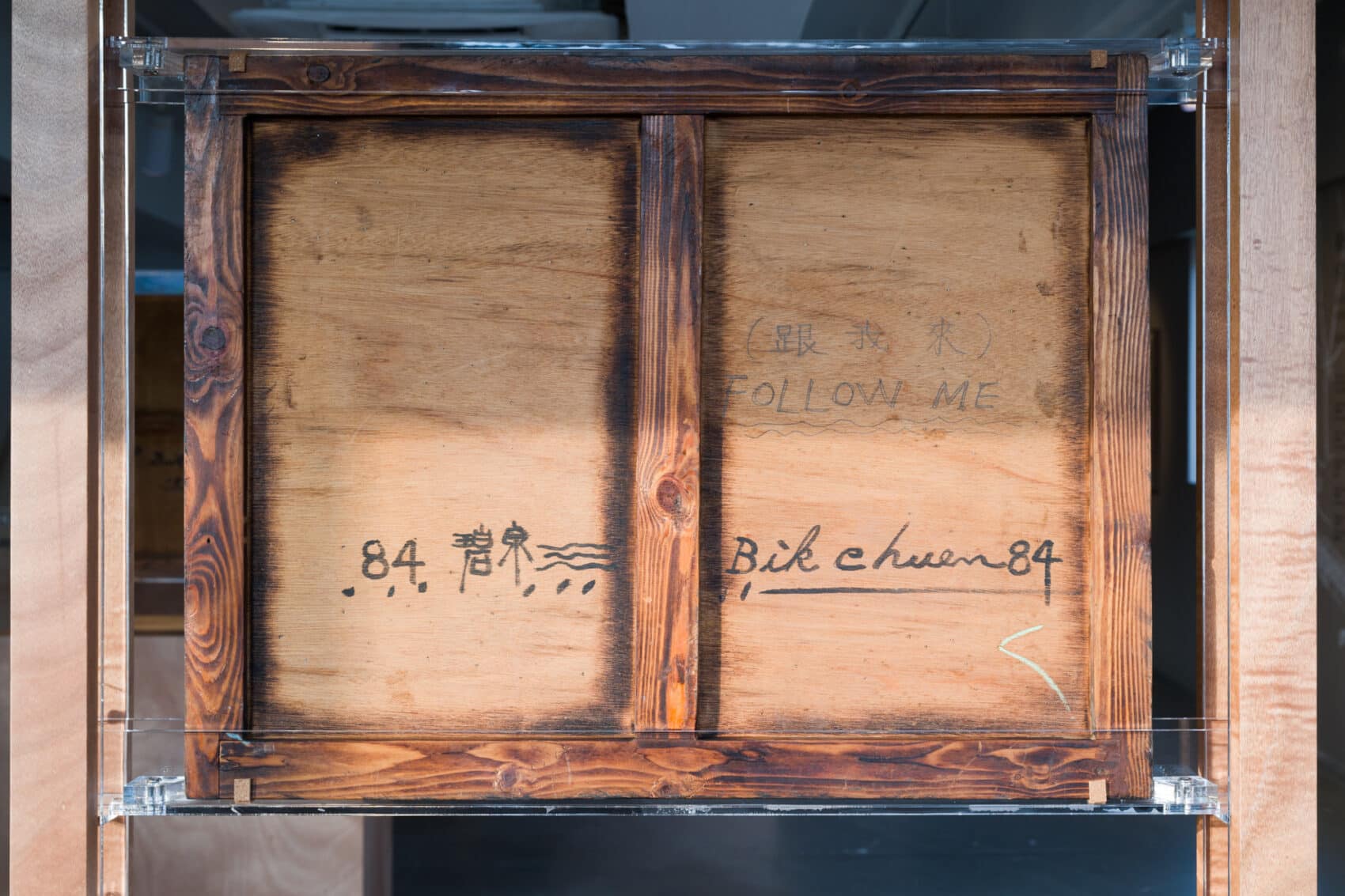

The process of creating collagraphs from lacquer-sealed motherboards was equally laborious. Laid flat on a tabletop, the motherboard received layers of dampened paper, pounded into place with various tools, like brushes (repurposed from straw brooms), coconut husk bristles, and tightly bound cloth. As the layers of paper were pushed into crevices and contours of the different textures of materials on the motherboard, color pigments were selectively added to specific areas. To this date one can see residues of pigment retained on the cracked surfaces of the motherboards. Each collagraph could be made up of thirteen to seventeen layers of rice and hemp paper; sometimes the collagraphs-in-process were left out to dry before being dampened again for more paper layers to be pounded in. The making of collagraphs was a sonically rich process as various dabbers pounded on the motherboard created different sounds. It could take up to three days for a collagraph to dry. When the finished collagraph was finally completely air-dried and unmolded from its motherboard, Ha would sign and give an edition number to the ones that he was satisfied with. (Figure 3)

When I first encountered Ha’s motherboards, it was seven years after I started engaging with Ha’s legacy. From 2013-2020, I was Asia Art Archive’s lead researcher for processing Ha’s materials, which involved the relocation of over six hundred boxes of photograph material, printed matter, and book collages to a dedicated project space for reorganizing, selective digitization, and a process of advocacy so the materials could find permanent homes in institutions as M+, Asia Art Archive, The University of Hong Kong, and the Baptist University of Hong Kong. With the permission of Ha’s family, his personal library of over five thousand books was gifted to individuals and organizations so they could have afterlives in other personal and organizational libraries. Seven years and six hundred boxes later, I found myself standing in front of the room that was previously blocked off by boxes, where Ha stored his motherboards. That day, two friends and I set up a make-shift photo studio to document the fronts and backs of the 108 motherboards. The process of documenting the motherboards was physically demanding, as each motherboard weighs around five kilograms. Excitement and anticipation were palpable as we shuffled within the tight space inside the Thinking Studio to move out each motherboard. You never knew what the next motherboard was going to look like, or what was going to be on its backside. (Figure 4)

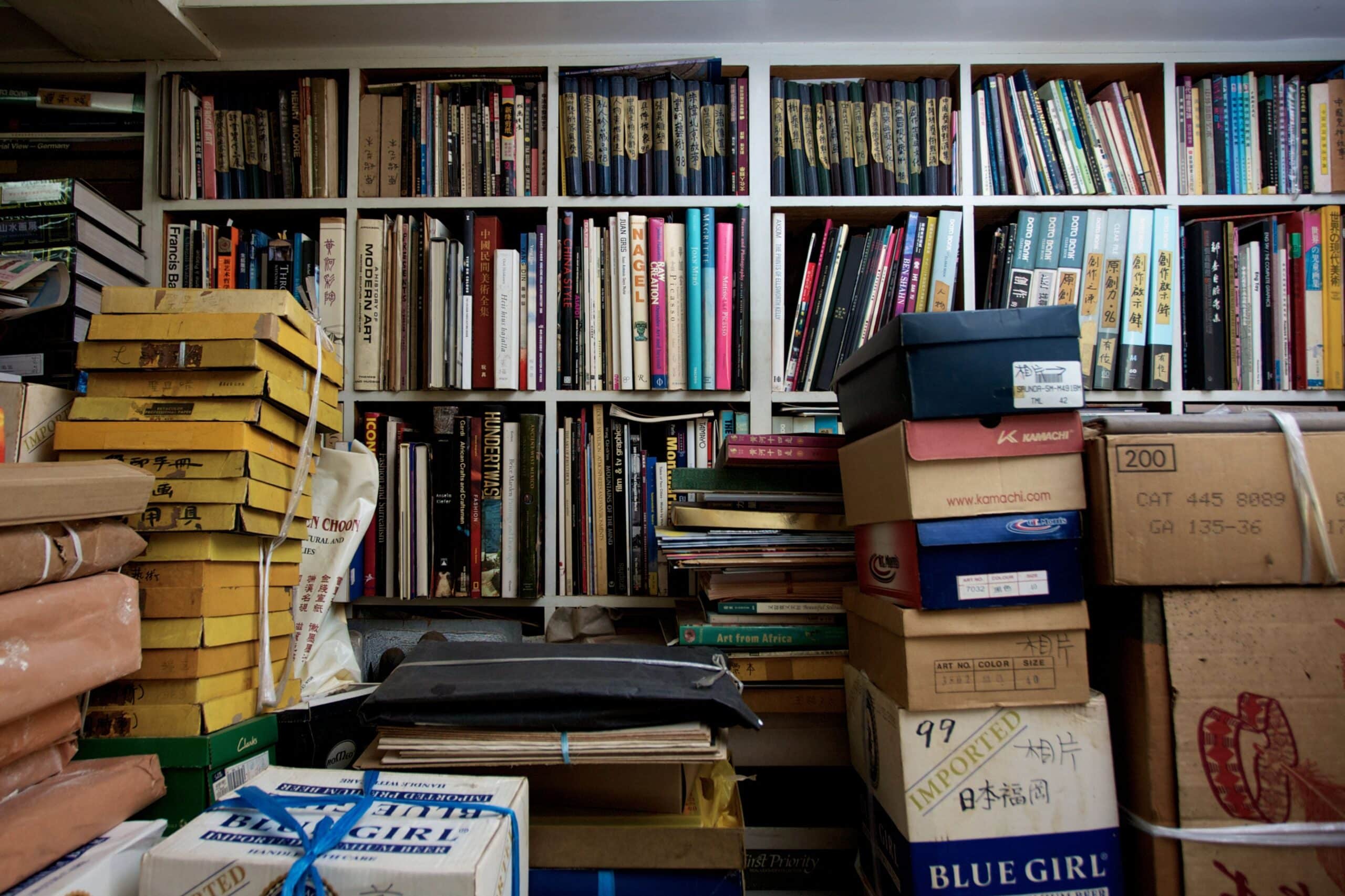

Ha’s motherboards qualify as printmaking tools and relief sculptures simultaneously. Ha kept his motherboards away from public view during his lifetime, storing them inside a dedicated room within his Thinking Studio, where he amassed fifty years’ worth of visual sources that functioned as his creative repository. As an artist who did not receive any academic training, Ha satiated his desire to learn about art by accumulating magazines, photographs, and books about art and other disciplines for forty years. This collection of materials filled the apartment adjacent to the living quarters of the Ha family, on the top floor of a walkup in To Kwa Wan. Ha named this space of accumulation and processing his Thinking Studio, an indication that that “thinking” for him was an act that needed a space that was deliberately cultivated. Thinking, for Ha, too, was a tactile act, as the physical accumulation inside the Thinking Studio necessitated a certain movement that wove through the materials, bookshelves, boxes, and furniture. (Figure 5)

Para Site, one of the first independent art spaces in Hong Kong and now one of the most recognized art centers in the region, extended an invitation to me in 2024 to show Ha’s motherboards and collagraphs. At that time, I was frantically tried to finish my PhD dissertation, unsure about how I would transform the dissertation chapter on Ha’s motherboards and collagraph into an exhibitionary experience. I wanted to honor the state in which the motherboards were found: intimate, enigmatic, and promising discoveries. But at the same time there was the undeniable desire to lay things out, to display them in a way that invites close observation. A year and a half later in 2025, some of Ha’s motherboards and collagraphs were displayed in public for the first time at Para Site, Hong Kong. Reframing Strangeness: Ha Bik Chuen’s Motherboards and Collagraphs, staged a selection of Ha’s motherboards, collagraphs and gouache drawings to resurface his printmaking practice, which has largely receded from public view.

The exhibition was one of reversals in several ways. First, the presentation of Ha’s now-dormant printmaking tools as relief sculptures opened up the question: could the motherboards be considered and treated as artworks? The exhibition’s focus was on the motherboards, only a few were displayed with their ‘offspring’ collagraphs. The collagraphs signaled towards the primary function of the motherboards as printmaking tool. In the exhibition, they guided viewers to consider how the image could have transferred from matrix to print. They were also placed near windows that opened towards the urban landscape. This gesture served as a reminder that Ha drew materials from the external into his internal world of image making. Meanwhile, the proposition of Ha’s drawings that mirror some of the motherboard imagery as ‘parallel lives’ suggests an alternative to the usual sketch-to-artwork relationship, and offers a re-reading of Ha’s interconnected art practice, the core of which was his motherboards. (Figure 6)

In the Thinking Studio, Ha’s motherboards were stacked next to one another as if they were books, their handwritten titles taped on the sides of the boards. When producing collagraphs, they were laid flat on a worktop. At Para Site, we placed the motherboards upright on a specially designed display system that made their fronts and backs visible. Three pairs of the motherboards on display leaned on each other at a forty-five degree, creating a hut-like structure that invited the visitors to lean forward and observe the motherboard’s surface textures closely. Seeing the motherboards from different angles was a reminder and a physical mirroring of the way Ha pored over these surfaces.

Yet another reversal in Reframing Strangeness lied in the inversion of private and public. As Ha’s previously unseen motherboards were put on public display, Ha’s very own worktable, once placed inside his Thinking Studio where he worked in private, also became the center of the exhibition’s social space. Benches placed around the table encouraged visitors to sit, gather, converse, debate, linger. The green and white tiles of the Thinking Studio made a temporary appearance on Para Site’s floor too, as a gesture of citing the original location from which the objects on display came. (Figure 7)

By presenting Ha’s motherboards as aesthetic objects, Reframing Strangeness urged viewers look closely and imagine Ha’s process, to explore something they had not encountered before, and therefore something strange. It invited visitors to observe how materials on the motherboard surfaces are extracted from their original urban environment, manipulated and reconnected to form images. They could consider how the motherboards’ composite nature tells a story of Hong Kong at the cusp of large-scale societal change in the mid-twentieth century and explore how the motherboards’ surfaces became a place for Ha to experiment with repetition and modernist visual vocabulary, and nurture his obsession with record keeping. On these surfaces, otherworldly creatures hover mid-air and ancient Chinese oracle bone scripts are combined with modern Chinese traditional characters and letters from the Roman alphabet. Organic materials become frozen in time and space, forming another kind of still life as they are embalmed with glue and industrial lacquer, fitted snuggly around fragments of other formerly quotidian things.

Ha’s creative practice lives many afterlives. One of them is the reorganization of his personal collection that has since spawned various artist projects, exhibitions, and biennale presentations responding to questions of archives, artists’ posthumous legacies and the slippages between fact and fiction. Reframing Strangeness is one afterlife that extends the others discursively through a series of public programs. These included a two-day assembly with Jogjakarta-based research group Hyphen—, a podcast series with London-based publisher Afterall and printmaking workshops with Hong Kong-based artist Kensa Hung. These programs brought together practitioners across different generations, geographies, and disciplines whose practices share affective resonance. We all have centered our own practices around remembering other people lives; we grope for the boundaries of meaning making in conservation, reproduction and manipulation of materials. Reframing Strangeness is also a reunion of sorts on Ha’s 100th birthday, bringing together practitioners who have worked with Ha’s legacy in the past decade, including architects Sarah Lee and Yutaka Yano of SKY YUTAKA, Max Tsoi of MAJO design, and editor and translator Wing Chan.

Sometimes things return to public life with more joy and lust for life than could be anticipated. Sometimes this happens at a time when zones of darkness and unknowable changes weigh down on social and political processes. Sometimes, one’s human and non-human companions re-illuminate strangeness, and one follows. (Figure 9)

Michelle Wun Ting Wong is Part-time Lecturer in Art History at The University of Hong Kong, where she received her PhD in 2025. Her doctoral research examined Hong Kong artist Ha Bik Chuen (1925-2009), exploring relationships between cultural modernity and artistic modernism in postwar Hong Kong. Her current research investigates travels of artists of Chinese descent across mid-twentieth century East and Southeast Asia and how these experiences shaped their projections of cultural China. Previously Researcher at Asia Art Archive, Wong’s work has focused on Hong Kong art history and histories of exchange and circulation through exhibitions and periodicals. Her writing appears in Southeast of Now (2019) and Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art, 1945–1990. Recent curatorial projects include Reframing Strangeness: Ha Bik Chuen’s Motherboards and Collagraphs at Para Site (2025), Portals, Stories, and Other Journeys at Tai Kwun Contemporary (2021), and Afterglow at Yokohama Triennale 2020. She holds degrees from Wellesley College (BA), Courtauld Institute of Art (MA), and The University of Hong Kong (PhD).