These photos accompany and expand upon an essay in the latest, and special, issue of our sister print journal, positions: asia critique entitled Neng and China’s Long 1980s: A Reevaluation. The issue originated in a conference held the autumn before the pandemic, in October 2019, and my thanks again to Ying Qian and Nick Bartlett of Columbia and Barnard for inspiring so much fascinating work. They prompted this first public foray into the archive of journals, letters and photos of my years in Beijing as a student and journalist, from 1979-1982, and then my time as a tour guide earning the money to support writing up my thesis, from 1982-1985.

What associations did the word buzzword neng carry in China? The “long 1980’s” from Opening and Reform in 1976 until the early 1980s, was a period of unparallelled transformation and sense of “can do:” nengyuan meant energy, source and resource, nengli denoted capacity and potential and nengliang, energetics and momentum.

My own essay in the special issue on neng, entitled 1979/1984: of scholarship, sinological tourism and thermoses, explores the poetics, technology, and meanings of the China-made thermos to reflect on my time in China as a student and later a tour guide in the years of the Long Decade. This marvelous “ritual vessel” of warmth provided a “social and economic infrastructure,” delivering hot water in Beijing’s cold winters. I was among the first American exchange students at Beijing University in 1979, and remember how fetching hot water in thermoses from the same place as all my Chinese classmates meant sharing in a sociality premised on conservation, sustenance, warmth and equality. Later, talking about leading boat tours down the Yangzi River to visit a thermos factory, among other destinations, I reflect on the affordances provided by the thermos, which embodied the contradictions between insulation as isolation and the warmth that the insulation kept. The essay ends by turning to the geopolitical tensions and circulations of the current historical moment and its resonances with the time of my first years in China.

Although I do not use the concept in the essay, I realize now that I approached the thermos during the long 1980s as the materialization of a shi: a very old term in Chinese aesthetics and philosophy meaning propensity, disposition, tendency, a sense of what can happen out of whatever “setup” of people, things, location and timing you have at hand. The thermos materialized the shi of my life as a student and later as a tourguide. As a student, its elements of frugality in energy use, along with its sharing from a central hot water source to fill them, became an affordance of a socialist style. Its efficacy lay in its ubiquity from city to countryside, from the halls of state to the halls of universities, to China’s trains and boats—thermoses were everywhere, carried by everyone regardless of status. There is more to say: about how seeing the world as sets of, overlays of, networks of “shi-forms” leads us to appreciate contexts and situations over individual actors or items. But how it also subtly emphasizes the ineluctability of the materiality of process once it is set in motion, and how, since the dao is infinite motion, we can never escape the materiality of its, our, forms.

“During the summers of the mid-1980s I earned the money to write my dissertation by working as the on-board Sinologist for the M.S. Goddess, a boat that was leased by Lindblad Travel from the Chinese Party-state. They ran tourists up and down the Yangzi River, through the magnificent Three Gorges, moving them between upstream Chongqing in Sichuan province down to Yichang City in Hubei, where there were locks for the boats to descend into more placid waters. This was before the great inundation of the Gezhouba Dam that tamed the wild and dangerous river that had tortured and blessed the farmers of her floodplain for millennia.

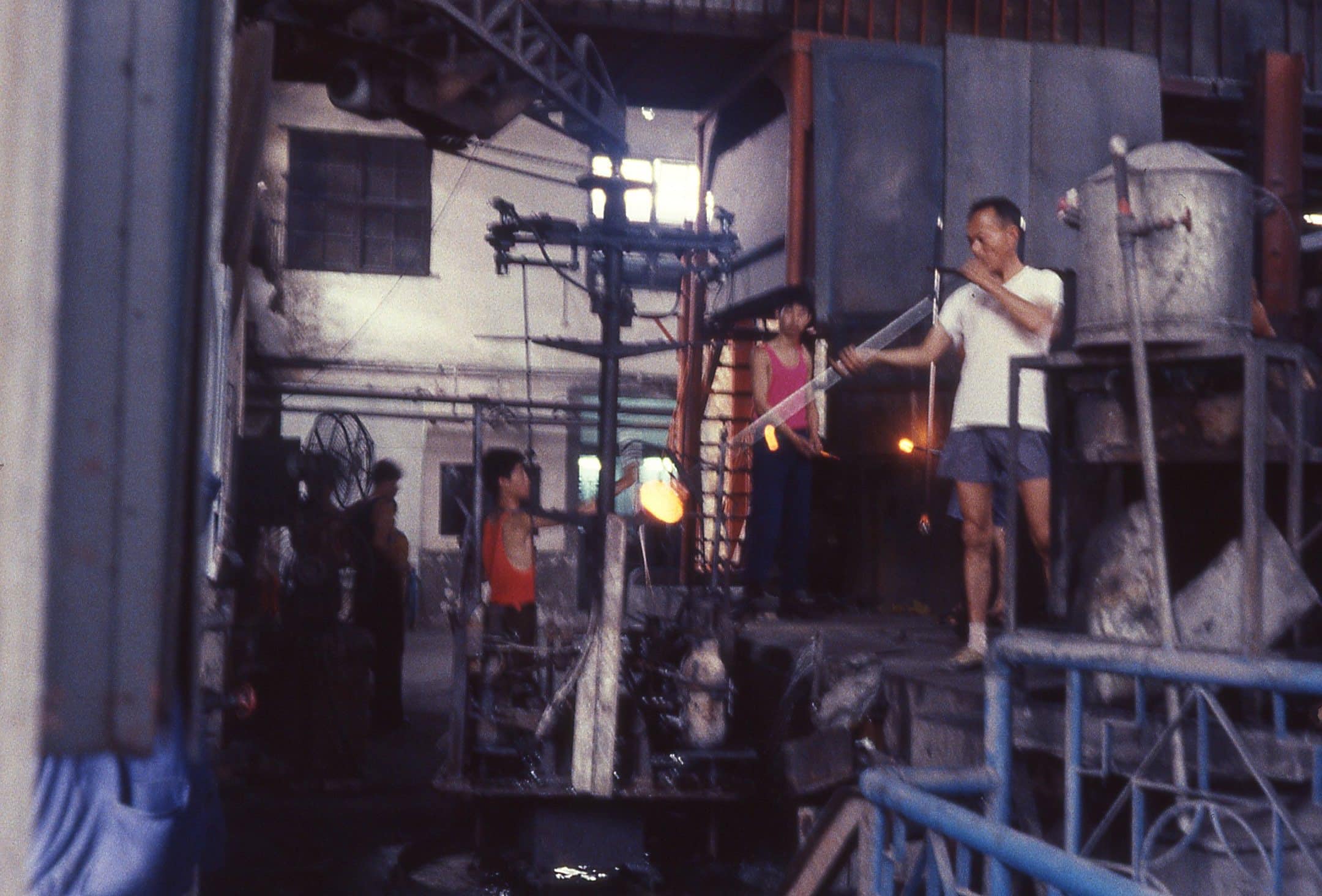

The thermos factory was located at Shashi City, in south Hubei province in the middle reaches of the Yangzi River. Our groups of about twenty tourists would be taken round to view each phase of the intricate process of blowing two glass bottles, and then inserting one into the other, coating them in reflective silver. The exquisite, feather- light baubles were then suspended within metal canisters. What began in the bright glow of fire, hung sealed in darkness, its mission to protect any heat from escaping except into our drinking mouths.

Bins of broken glass at every stage littered the place. The factory was hot and workers were alarmingly unprotected, as were we. Our small crowd emerged, sweating, at the end of the tour into a bright showroom of thermoses of all sizes, in a range of colors and bearing patterns of flowers and fruits, panda bears and beautiful veiled women.”

These photos document a bygone stage in China’s industrialization. China still leads the world in thermos-making: one out of every three glass thermoses is produced in China, and 70% of these come from the city of Yongkang, ten hours by car east of the Shashi City of these photos. Video from the Kuangdi Industry and Training Co, also of Zhejiang province, demonstrates the mechanized production of thermoses made of stainless steel that have almost completely replaced the original glass vacuum ones. Just as a lot of robotics have replaced the sweating, fragile humans that produced the silvered, fragile glass.

The Sinologist Francois Jullien spent a lifetime “translating” the key term shi into French and English in the fullest sense, beginning with his brilliant first book The Propensity of Things: Toward a History of Efficacy in China .

Shi has its origins in the martial life, where “potential is born of disposition in military strategy” (Jullien 25). In pre-Han dynasty China, it became an anchor for analyzing and training in expressive forms from calligraphy, to painting through poetry and prose. The sense of shi as disposition means the organization of elements into a vibrant, dynamic whole that can never remain static; you can see its use in situating the human as one component of a cosmos conceived of as constant change. Shi became a keystone of my own thinking about the role of form in human life and of how aesthetics undergirds politics as one of its necessary pleasures, rather than distracting from it. Thinking of the world in terms of its shi has cosmic implications that link us from the balance within calligraphically-inked words made by a brush to a politics that prefers indirect strategies from shi/positions of strength, both functioning equally to exploit the infinite potential of the Dao. Jullien: “Ultimately, because the absolute causality constituted by the dao never becomes immobilized in any one disposition, it remains forever inexhaustible” (34). The embodied person, in other words, labors creatively to create a material world that in turn creates them—dialectically and endlessly.

Elements take form as shi, and shi folds within itself its own processes of becoming and the results of that becoming. Shi are aesthetic forms that travel through time with suppleness, flexibly unrolling propensities within situations that are made to seem utterly natural; one of favored metaphor among Chinese writers was that of the round rock (in its shi of roundness) that rolls inevitably downhill, while the cube just sits there. Some shi I am writing about now are the kin-aesthetics of filiality (xiao) that is currently being revived in China.