Artist Tada Hengsapkul and curator Thanavi Chotpradit explore the underwater afterlives of the Cold War.

YOU LEAD ME DOWN, TO THE OCEAN

Tada Hengsapkul & Thanavi Chotpradit

In 2001, I opened a project to rehabilitate the coastal resources in Narathiwas province. Many Governmental organizations were helpful in the effort. It was a heartening experience, because it helps improve the livelihood of the poor, you know, those who live almost in hopelessness, poor, very poor. The organizations that support this project include the Department of Fisheries, the Royal Thai Navy, the State Railway, and the Department of Highways. The State Railway, for example, donated broken train carriages. When I saw them, I was confused. How will the carriages be enjoyed by the fish? I couldn’t understand it. I didn’t have a clue back then. But the State Railway donated the carriages, the Department of Highways donated concrete pipes, etc. Afterwards, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration also donated broken-down garbage trucks. It was an education for me, a queen who knew nothing. I learned from the needs of the people. I learned from all of you who are helping to fix these problems. So, these things were dumped into the sea, into where they considered good locations, and became artificial coral reefs. And the Navy went and filmed the thing for me. Wow, I was blown away. People dumped all these objects down, and the fish swarmed in in big numbers. They thought, boy, these are good houses for us. They practically lined up for it. If they hadn’t filmed it, I wouldn’t know. So many fish came. And my people told me that catching fish becomes a breeze. They get good catches now...

The above is an excerpt from a royal speech that Queen Sirikit, the queen consort of King Bhumibol (currently Her Majesty Queen Regent Sirikit, The Queen Mother) delivered to an audience of well-wishers at the Dusidalai Hall, Chitralada Villa, on the occasion of her birthday on 11 August 2009. The speech was published on the website of the Central Database System and Data Standard for Marine and Coastal Resources, Department of Marine and Coastal Resources. One year later, at the end of July 2010, the Thai army transferred the remains of 25 T-69 II tanks out from Surathampitak Military Camp, Nakhon Ratchasima province, and gave them over to the Department of Fisheries to be repurposed into artificial coral reefs in the Gulf of Thailand, Narathiwas province, as part of the Royal-Initiated Coastal Resources Rehabilitation Project under Her Majesty’s patronage.

Eight years later, the artist Tada Hengsapkul conducted research in the National Library of Thailand and the National Archives of Thailand, and created an art project that pieces together a chain of events which began during the Vietnam war, in which Thailand played a crucial role in supporting the US army from around 1955–1975, up to the Vietnamese border raids in Thailand during the years 1979–1989. Military tanks bought from China in 1987 for the fight against Vietnam in these border raids were eventually withdrawn and repurposed into artificial coral reefs in Narathiwas province in 2010. Documents, images, old publications and newspapers that were uncovered by Hengsapkul in these archives brought him back to Nakhon Ratchasima province—the city is both his birthplace and the location for one of the US military bases in Thailand. Hengsapkul’s archival research was conducted alongside his field research in that area. The research led him to an antique collector who wishes to remain anonymous. In his possession is a correspondence between a Thai soldier deployed in the fighting in Vietnam and his family in Bangkok. These personal letters are primary evidence that reveals the thoughts and feelings of the minor characters affected by this global political conflict. This evidence allows Hengsapkul to construct a narrative in which the voices of a low-rank soldier and the regular citizens around him can be heard. In a climate where mainstream history stresses the events surrounding important figures and their roles, a work of art offers asylum to the stories and memories that have yet to become, are becoming, or never will become part of historical narrative.

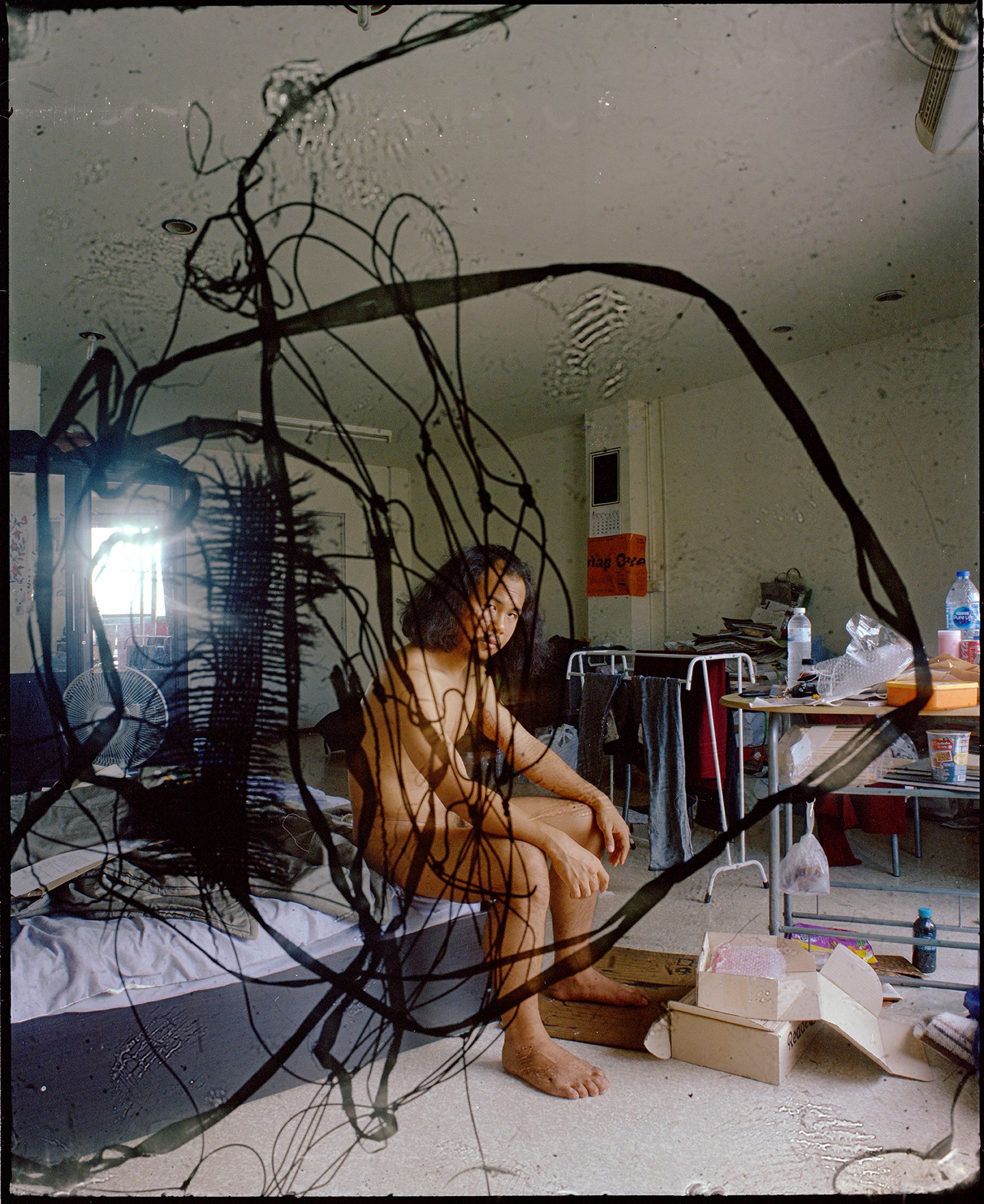

YOU LEAD ME DOWN, TO THE OCEAN by Hengsapkul is an installation that transforms the exhibition space into an underwater world. In the dark room, an image of a military tank on the seabed of Narathiwas province, amidst schools of gliding fish, is projected onto the wall. The projection casts light onto the ceiling that has been covered in hologram fabric, from where the light is then refracted onto a narrow glass slit that looks into a smaller exhibition room on the mezzanine floor. The installation creates a strangely enigmatic atmosphere, an immersive theatrical space where the tank gun pointing at us appears simultaneously beautiful and intimidating. The tank may seem harmless now, having been turned from an instrument of war into a tool for the conservation and rehabilitation of marine environment, a part of a Royal-initiated project with an aim to better the lives of Thai fishermen; yet, conversely, we can also view it as a symbol for an expansion of power whose ominous shadow looms large everywhere we turn. The dive down to the bottom of the ocean is both a physical reality for the underwater camera crew who took us to see what they saw, and a metaphor for our sunken state under a military dictatorship that is a legacy of the Cold War. The way out is still a long way up, and the naked bodies in the photographs on the mezzanine floor represent us at present, still swimming in the depth.

National ideology is often a difficult thing to shake off. The security of the three main institutions—nation, religion and monarchy—was heavily emphasized during the Cold War, while communism was painted as an external devil against which all Thais must protect our kingdom. This was a powerful rhetoric, and the military is a key component in its working as well as a main beneficiary. Such heroic rhetoric evoked patriotism and the spirit of the age, but even so, the constant news of injuries and deaths during wartime exposed a hidden chamber inside the human psyche that no grand ideology can fully close off. Amidst the words offering love and support between husband and wife, there are also sentences that imply fear. Even behind the soldier’s good morale, buoyed up by his belief in supernatural powers, a fear was lurking. There were also signs of anger and disappointment towards the institutions to which these people devoted themselves. The poverty, the separation, the homesickness, the longing for family and loved ones. In the little room beneath the mezzanine floor, where the light from the underwater image cannot reach and where one is cut off entirely from the stifling underwater atmosphere, from the point of the gun and from the grand institutions, seven letters which carry these feelings await their readers, waiting to be noticed and heard by the visitors who are their descendants.

YOU LEAD ME DOWN, TO THE OCEAN is constructed from events in history and personal stories from different periods. Inside the pitch black, theatrical exhibition space, the underwater scene hoards up the times stretching from the past to the present. Yet there is no clear chronological order. The misplaced pieces still require an interpretative interweaving, for these traces are secured together by artistic process. The past through the artistic lens of Hengsapkul does not resemble a textbook narrative. It contains no didacticism and no moral appeals. The artist is not even playing a historian or an activist. His art is simply an unveiling, in a hypothetical space, of that which has been covered up. In this space, the image, the light and the sound are a blend of reality, facts and synthesized elements. When fragments of information and memories from official and obscured sources have been processed by art, things which do not relate to each other in any way become linked through aesthetic means. The resulting enigma is mesmerizing. Light, darkness and reflections; stories of a period in the life of a family of strangers, and the hope that one day the green color of the camouflage uniform will melt and fade away.

Thanavi Chotpradit

The text is written on the occasion of the exhibition YOU LEAD ME DOWN, TO THE OCEAN by Tada Hengsapkul, curated by Thanavi Chotpradit at Nova Contemporary, Bangkok, June 6-July 21, 2019. The exhibition consists of two video installations, four photographs and a set of printed correspondences between a Thai soldier deployed in the fighting in Vietnam and his family in Bangkok.

In a climate where mainstream history stresses the events surrounding important figures and their roles, a work of art offers asylum to the stories and memories that have yet to become, are becoming, or never will become part of historical narrative.

Thanavi Chotpradit

Thanavi Chotpradit

YOU LEAD ME DOWN, TO THE OCEAN. Artist Book (Sample Page). 2018. Tada Hengsapkul and Nova Contemporary

The way out is still a long way up, and the naked bodies in the photographs on the mezzanine floor represent us at present, still swimming in the depth.

Thanavi Chotpradit

Thanavi Chotpradit