Jennifer Dubrow investigates the role of poetry in contemporary protest in India at a turning point in the country’s political history.

On December 17, 2019, a student protest at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur was held in solidarity with students at Jamia Millia Islamia who had been brutally attacked by police on December 15. The protest included a recitation of an Urdu poem, commonly known as “Hum Dekhenge” (literally, We Shall See), by leftist poet and revolutionary Faiz Ahmad Faiz (1911-1984). In a video posted on Twitter, a student recites the poem, which he reads from his cellphone, to a crowd of listeners, some of whom mill about and some of whom listen attentively, with the crowd applauding at certain lines. This recitation of the poem soon became the center of a controversy, when a post-doctoral faculty member at IIT lodged a complaint against the poem and its performance, claiming that its lines aroused communal sentiment. IIT-Kanpur responded by establishing a committee to investigate the complaint. A public debate in the media ensued, as prominent poets, a former Indian Supreme Court judge, and journalists and intellectuals discussed the poem and its meaning.

First composed in 1979, Faiz’s “Hum Dekhenge” has become a rallying cry for protests both throughout India and around the world against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), passed by India’s Parliament on December 19, 2019. The CAA proposes a religious basis for citizenship for refugees who have entered India from the neighboring countries of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Under the new amendment, refugees who are Hindu, Jain, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Parsi, even if they do not possess identification papers, may receive Indian citizenship within 6 years. Notably missing from this list are Muslims, who, according to the 2011 Census of India, make up 14.2 % of the population, for a total of 172 million people. According to a more recent estimate, India’s Muslims, at 195 million people in 2020, comprise the third largest Muslim population in the world, after Indonesia and Pakistan. The specter of citizenship being granted on the basis of identification papers—which are notoriously difficult to obtain in South Asia, especially for the poor—is particularly scary. It elides the history of mass migration and the large-scale passage of refugees across the border during the 1947 Partition and the 1971 War of Independence that led to the creation of Bangladesh. The CAA represents a fundamental reworking of the citizen’s relationship to the nation-state in South Asia. It moves from citizenship based on residence within India to citizenship based on religion. While the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s move has roots in the last seventy years, particularly in Assam, where the idea of a National Register of Citizens (NRC) was formed, the CAA and the threat of a nation-wide NRC, which has been promised by the government, alongside the recent annexation of Kashmir (with the abrogation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019) and other policies and Supreme Court verdicts, makes this a turning-point.

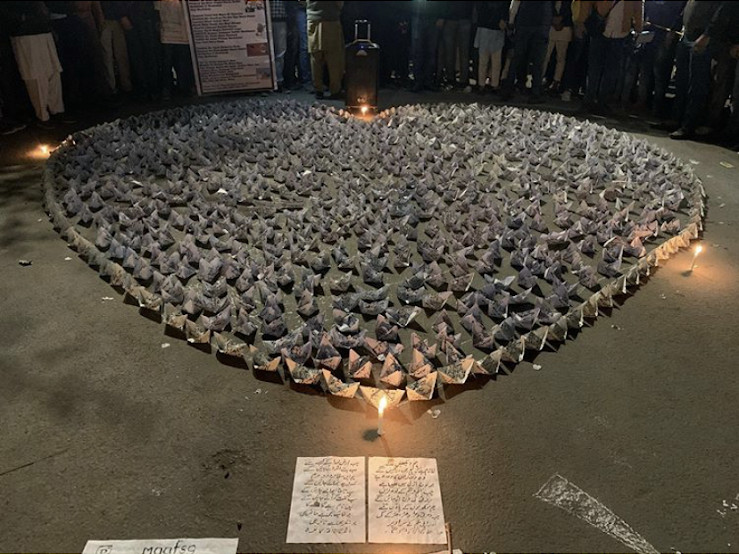

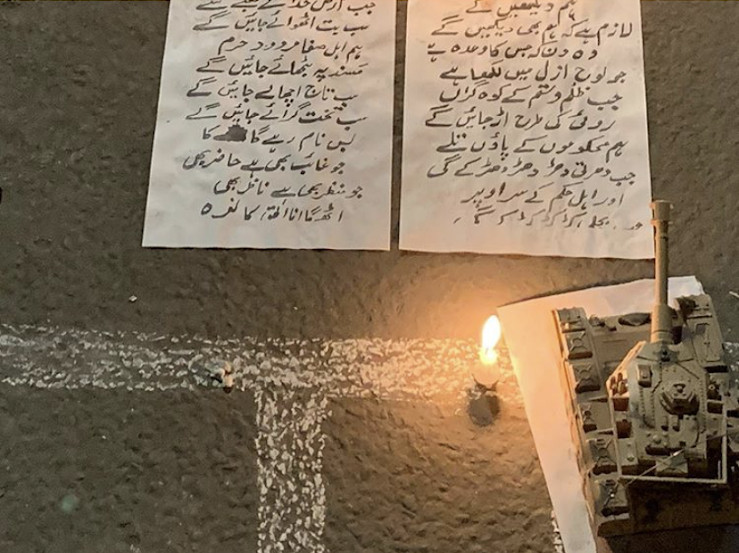

Urdu poetry has been central to the protests. The use of “Hum Dekhenge,” as rallying cry, song, visual art, and internet meme, speaks to the widespread citation and circulation of certain Urdu or Hindi/Urdu poems during the anti-CAA protests. “Hum Dekhenge” has been extensively recited or sung during the protests. In a rendition posted on YouTube on December 29, 2019, the poem is sung on the steps of the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) campus, which on January 5 saw violence against students and faculty by an armed mob. In an anti-CAA protest in Cape Town, South Africa, a woman named Kathyayini Dash stood outside the Indian consulate, microphone in hand, passionately singing the poem. The poem has also inspired visual artists. On January 13, 2020, a group of art students installed an artist protest at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi, the site of a 24-hour sit-in celebrated as a woman-led protest. The artists wrote lines from “Hum Dekhenge” onto sheets of paper, folded them into boats, and laid them out in the shape of a heart, with the text of the poem placed at the base. The text is accompanied by a toy tank, whose size, an artist explained in an interview given to The Quint, was meant to show the military’s small power when compared to that of poetry.

Other poems popular among protesters are Habib Jalib (1928-1993)’s “Dastur” (The Constitution), originally composed in opposition to Pakistan’s 1962 Constitution instituted by General Ayub Khan, and Faiz’s “Bol,” published in his 1942 collection Naqsh-e Faryadi, which exhorts the listener to “Speak, for your lips are still free.” Thus poetry transcends its original time and contexts. The connection between Hindi/Urdu poetry and Bollywood cinema, begun in the 1940s and 1950s, is evidenced by two widely-cited poems by Bollywood lyricists, Rahat Indori (1950- ) and Varun Grover (1980- ). “Hum Dekhenge” has also been translated into other languages including Bhojpuri and Kannada, and sung in demonstrations. The circulation of these poems illustrates the nexus between Hindi/Urdu poetry, cinema, song, and protest in South Asia.

The use of Faiz’s “Hum Dekhenge” in the anti-CAA protests also illuminates the direct link between Urdu poetry and the idea of art as action, which became a clarion call in the 1930s. As the Hindi-Urdu writer Premchand (1880-1936) declared in the inaugural address to the first Progressive Writers’ Conference in 1936, “As long as the aim of literature was only to provide entertainment, to put us to sleep … it had no need of action. … The only literature that will pass our test is that … which instills in us dynamism and restlessness, not sleep.”1The formation of the All-India Progressive Writers’ Association (AIPWA) in 1936, with which Faiz was affiliated, marked a turning-point for modern art and literature in the Indian subcontinent. Premised on the rejection of cultural conservatism and tradition, as well as on the idea of art as awakening the masses toward political action, the Progressive Writers’ Movement rewrote the relationship of art to politics. Among Hindi/Urdu writers, it harnessed the production of poetry and prose to political and social revolution. Faiz himself was imprisoned several times for his support of leftist politics in Pakistan, while other writers associated with the movement were charged with obscenity and forced to defend themselves in court in both India and Pakistan.

Textual and Performance History

Despite the poem’s wide circulation, “Hum Dekhenge”’s textual and performance history is not well known. “Hum Dekhenge” was first published in Faiz’s 1980 collection of poems, Mere Dil Mere Musafir (My Heart, My Traveller), composed toward the end of his life. This collection illustrates Faiz’s leftist internationalist stance, informed by his experiences with both the Progressive Writers’ Movement and the political turmoil of Pakistan’s early years. After the military dictator Zia ul-Haq’s rise to power, Faiz was targeted and put under surveillance for his support of the Pakistan People’s Party, which led him to leave Pakistan. He spent five years outside Pakistan, living mostly in Beirut, where he worked on a small salary as the editor of Lotus, the journal of the Afro-Asian Writers Association, active from 1958 to 1979. During his time in Beirut, Faiz witnessed the suffering of Palestinians in Lebanon and abroad. Mere Dil Mere Musafir includes poems on the suffering of Palestinians, as does his next collection Ghubar-e Ayyam, which his grandson Ali Madeeh Hashmi argues should be considered as an appendix to Mere Dil Mere Musafir2. Mere Dil Mere Musafir is dedicated to Yasir Arafat, whom Faiz met while in Beirut:

During this time Faiz also visited London, Moscow, and the United States. “Hum Dekhenge” is labelled, “America, January 1979,” though it is not clear where in America he composed the poem.

After first being published, the poem suffered an unusual textual history. Faiz removed “Hum Dekhenge” from his collected works, Nushkhā-e Vafā, published in 1984 by Maktaba-e Karvan in Lahore. The reasons for this omission are unclear. According to one source, Maktaba-e Karvan asked for the poem to be removed because of its religious imagery.3 Another possible explanation is that the poem is too similar to another tarana in the collection. That poem, titled “A Song for the Mujahidīn of Palestine,” remains in Nushkhā-e Vafā. Its first two lines, “Hum jitenge/Haqqa hum ik din jitenge,” mirror very closely the first two lines of “Hum Dekhenge,” and so it is possible that because of the poems’ similarity Faiz removed “Hum Dekhenge.”

How, then, did the poem survive? Its popularity is in large part the result of a famous performance by the Pakistani singer Iqbal Bano. Bano sang “Hum Dekhenge” on February 13, 1986, at the annual Faiz Mela. This festival is held in February on Faiz’s birthday to commemorate his life and work. The day’s festivities would be followed in the evening by a concert at Alhamra Arts Council, on Lahore’s Mall Road.

Bano was a well-known interpreter of Faiz’s poetry, and that year’s concert had attracted an unusually large crowd. According to Hashmi, “a large number of political activists and workers” had gathered outside the auditorium, demanding to be let in. Hashmi’s mother Moneeza “told the assembled audience that she was going to open the doors and people could sit wherever they could find a seat.” Soon people were sitting “on the stairs, the floors, wherever they could find some space.” As Hashmi recalls, of Faiz’s poems “the loudest cheers were reserved for ‘Hum Dekhenge’,” and within that poem, for the verses “sab taj uchale ja’enge/sab takht gira’e ja’enge.” Bano was begged to perform the song again as an encore, and this performance was recorded by a technician at Alhamra. The performance’s subversive nature was immediately recognized by the authorities, who:

raided the homes of the organisers and many of the participants looking for any audio copies of the concert, especially ‘Hum Dekhenge.’ Many copies were confiscated and destroyed but my uncle Shoaib Hashmi had managed to get a hold of one copy and anticipating the crackdown handed it over to some friends who promptly smuggled it out to Dubai where it was copied and widely distributed.

Fortunately this recording has survived, and is available on YouTube. The audience’s reaction to the performance is raucous, with the crowd bursting into applause as soon as Bano starts singing the poem. The audience members clap along with the rhythm, applaud certain lines, and at some points, totally erupt. When Bano reaches the poem’s most directly anti-authoritarian lines, “sab taj uchale ja’enge/sab takht gira’e ja’enge,” the crowd goes wild, crying out and yelling, and then breaking into rhythmic applause, which the tabla player echoes for a few measures. When Bano begins to resume, the audience breaks into cheers of “Inqilab Zindabad” (Long Live the Revolution), a leftist slogan now used broadly across protests groups in South Asia, which they continue to chant as she sings several more lines. This reaction is a testament to the power of this poem to incite revolutionary emotion. We can probably credit Bano’s performance with “Hum Dekhenge”’s enshrinement in the corpus of protest poetry.

Relationship to Sufi & Quranic Imagery

“Hum Dekhenge”’s use of religious imagery has been at the center of India’s controversy around the poem. What is not well known about the poem is that despite Faiz’s leftist credentials, “Hum Dekhenge” draws on Quranic imagery and hinges on a core Sufi belief. While known popularly by its refrain “Hum Dekhenge,” the poem as originally published in Mere Dil Mere Musafir carries three words from the Qur’an as its title. These are: “Vabaqa Vaju Rabbik,” from Verse 27 of the 55th surah of the Qur’an, Ar-Rahmān. Translated as “the face of your Lord” in the Al-Azhar University-approved translation by Majid Fakhry,4 these three words present a central image in Sufi thought. The verse presents the face as all that remains after everything on earth is destroyed. As has been pointed out by others, this is an eschatological image, but it uses an established dichotomy in Sufi thought: between baqā, that which remains, and fanā, the effacement of the ego in the divine. The previous verse (Verse 26) states, “Everything upon her [the earth, or the soul, both feminine nouns] is effaced,” followed by Verse 27, “But the Face of your Lord, full of majesty and nobility, shall remain.” Verse 26 is eschatological, pointing to the final day of judgment, but Verse 27 presents the destruction of all in a Sufi context, where it is only the face of God that remains.5

Other images are best understood through reference to Quranic imagery. The poem’s third and fourth lines refer to “That day that was promised/that was written on the tablet of eternity (lauh-e azal).” The lauh-e azal refers to the celestial eternal table (al-lauh al-mahfūz) from which all knowledge is derived, including the Qur’an.6 The next two lines also reference a Quranic image: “Jab zulm o sitam ke koh-e girāN/Ru’ī ki tarah uR jāenge” (When heavy mountains of tyranny and oppression/Will float away like cotton). The image of mountains becoming as light and fluffy as cotton is found in Surah 101, Al-Qari’ah, which describes the day of judgment as: “The Day that men shall be like scattered butterflies;/And the mountains like tufted wool,”7 where the last words of Verse 5 can be translated more literally as “wool that has been fluffed up.”8 Faiz’s verse draws on this central opposition, where solid mountains suddenly become light and ephemeral like wool or cotton.

Most notably, the poem invokes the Persian Sufi Mansur Al-Hallaj’s famous exclamation, “An ul-Haq,” translatable as “I am God” but also “I am Truth,” by which Hallaj expressed the obliteration of man’s ego in the divine. This radical stance, which led to al-Hallaj’s execution in the 9th century, has led to confusion in the media and even among protestors themselves. As reported by Harish Trivedi, Professor of English at the University of Delhi, “there’s a joke going round that a student singing the song in a protest procession was stopped and asked by a reporter if he knew what he was singing. ‘So what is An al Haq?’ asked the reporter. The student said, ‘An al Haq … An al Haq?… Brother of Zia ul Haq?’”9 By citing this phrase, Faiz’s poem both references the Sufi critique of religious (and other) authority and invokes a fundamentally mystical way of perceiving and understanding God. This was meant as a criticism of Zia ul-Haq’s government, which imposed Shari’a-inspired religious laws (known as Huddud) on the country, but the critique can easily be transposed onto any human or political authority that takes away or threatens humanity’s fundamental relationship with God.

Translating Faiz

The difficulties of translating Faiz—and Urdu poetry in general—have been noted by scholars and translators. In particular, Faiz’s poetry’s deep imbrication within a web of established images and metaphors drawn from the Urdu and Indo-Persian poetic traditions presents challenges. As Naomi Lazard, one of Faiz’s first translators, noted about her process: “I asked him questions regarding the text. Why did he choose just that phrase, that word, that image, that metaphor? What did it mean to him? … What was crystal clear to an Urdu-speaking reader meant nothing at all to an American.”10 According to Victor Kiernan, Faiz’s other major translator, “Of all elements in foreign poetry, imagery is the easiest to appreciate, except when, as often in the Persian-Urdu tradition, it has symbolic and shifting meanings.”11 As I have argued elsewhere, Faiz’s poetry draws on the resources of tradition to invert them to new, and sometimes political, purposes. Part of what makes his poetry so fresh and quotable—and well-suited to political protest—is its multi-valence, its deep debt to, and reimagining of, the Urdu poetic topos.

To bring the impact of “Hum Dekhenge” to an English-speaking audience, I had to consider these various factors. How is one to transmit the dense networks of meaning underlying Faiz’s poem, and to render them in a form that communicates the poem’s rousing effect, its quotability, its rhetorical impact on the listener? I have made my best attempt below. But some things are lost in translation—in some cases, when networks of imagery could not be rendered into English, I chose to leave them out, so as to not interrupt the flow of the poem and what I see as its cumulative effect on the listener. I also chose to substitute “Hum Dekhenge,” which means “We shall see,” with “On that day” or similar phrases, because the finality of the future tense in the Urdu is what makes that line so powerful. This grammatical distinction is not clear in English. But what the Urdu phrase points to is the certainty that the day that has been promised will, indeed, arrive. I do not believe that sense is rendered in “We shall see,” but other translators are welcome to make their own decisions.

On That Day

That day will come

Yes, that day will come

That day we have been promised

When mountains of tyranny and oppression

will float away like cotton

And the earth will tremble and shake

under the feet of the oppressed

The sky will thunder and roar

on the heads of the arbitrators

False idols will be uprooted

from the Ka’ba of God’s earth

And the pure-hearted will be seated in places of honor

Thrones will be smashed

And crowns overthrown

On that day

Only the name of God shall remain

Who is both present and unseen

Who is both the observer and the perceived

On that day

The cry of “I am God!” will resound

The God that is in you and me

And the earth shall be ruled by those whom God created

The people, who are you and me

-America, January 1979

***

On February 23, 2020, mob violence broke out in parts of northeast Delhi, sparked by a speech in which a BJP leader, Kapil Mishra, issued an ultimatum to Delhi police to clear the road of Chand Bagh, in northeast Delhi, of anti-CAA protesters within three days or risk violence. Violence ensued, as armed mobs have barged into neighborhoods, attacking Muslim men and shops, setting cars and e-rickshaws ablaze, throwing stones, and in one case, vandalizing a mosque. Police have stood by, or joined in. And on my Twitter feed, someone has cited another Faiz poem, this time his 1974 “Dhaka ki vāpsi par,” composed as he returned from Dhaka with Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto as part of his work with the Pakistan National Council for the Arts. The poem becomes a kind of shorthand: a way of extending sympathy and solidarity not only to the residents of northeast Delhi, where Hindu and Muslim neighborhoods are being torn apart, but also to the estranged neighbors from the formerly East and West Pakistan. “We have become strangers,” the poem begins, “after so many meetings/When will we become confidants again?” And so, threads of intimacy and estrangement, trauma and longing, across local neighborhoods and national borders, are woven together into a web of suffering and loss. It is not surprising that this poem by Faiz, who, along with his progressive contemporaries, imagined alternative futures for the peoples of both India and Pakistan, can serve as metonym for the pain and suffering of the present day. Faiz and his fellow members of the Progressive Writers’ Movement stressed the universality of the human condition, as against the divisions of caste, class, language, region, religion, and nation. Faiz’s third-world internationalist stance, evident in the poems in Mere Dil Mere Musafir, envisions a global community organized around shared solidarities. In “Hum Dekhenge,” Faiz draws on the resources of Urdu poetry, including its Sufi and Quranic imageries, to invoke and create this common sense of suffering and hope.

© 2024 positions editorial collective. all rights reserved.